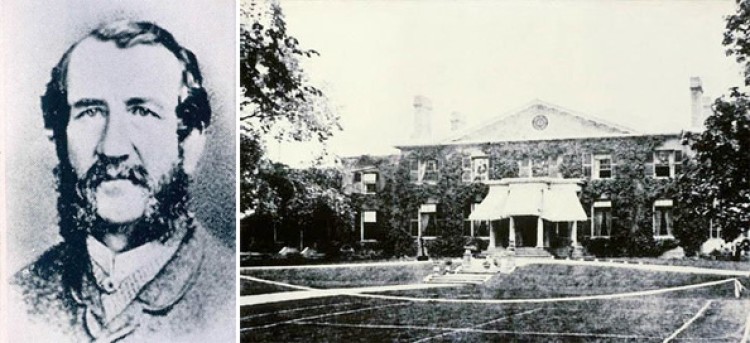

William Boulton

A History of Instability

Photograph courtesy of the Conservation Department, Art Gallery of Ontario. © Art Gallery of Ontario

George Berthon’s painting has had a history of instability, undergoing previous treatments in 1954 and 1973. In a presentation to The Grange Council in 2004, Maria Sullivan, the AGO’s conservator of paintings, stated that she had detected flaking paint and considerable paint loss in the Boulton portrait, and felt that its deterioration was close to becoming irreversible. She acknowledged that the work might have to be removed from The Grange unless it received a major conservation treatment.

Funds Towards Restoration

Gretchen and Donald Ross offered to donate funds towards the restoration of the work, allowing the AGO to begin its treatment in November 2004. The Canadian Conservation Institute in Ottawa performed a thorough analysis on tiny samples of paint taken from the work. Andrew Ornoch, a freelance painting conservator, was hired by the AGO to carry out the treatment under the supervision of Sullivan and fellow conservator Sandra Webster-Cook. The project was completed in September 2006.

Treatment Begins

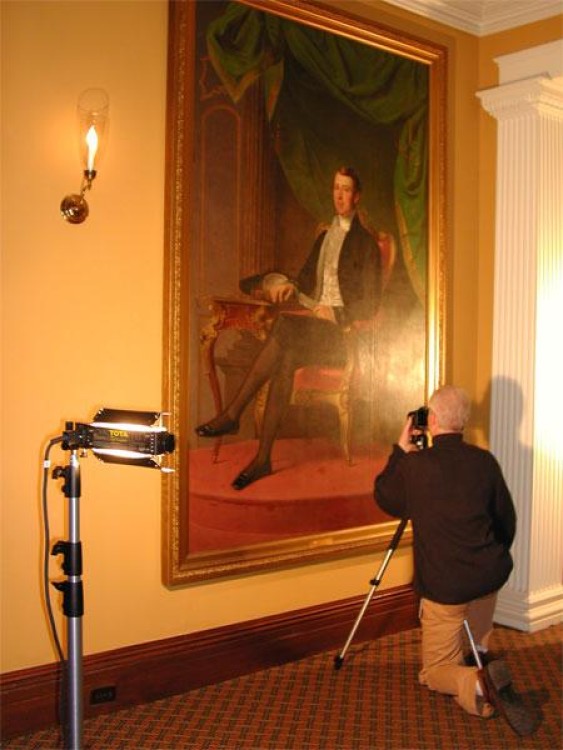

The treatment began with extensive written and photographic documentation of the painting’s condition. In this image, you can see conservator Andrew Ornoch photographing the painting in The Grange before it was removed for conservation. The fluctuating environmental conditions in The Grange, where the painting was displayed for decades, contributed significantly to the painting’s deterioration.

Excess Glue

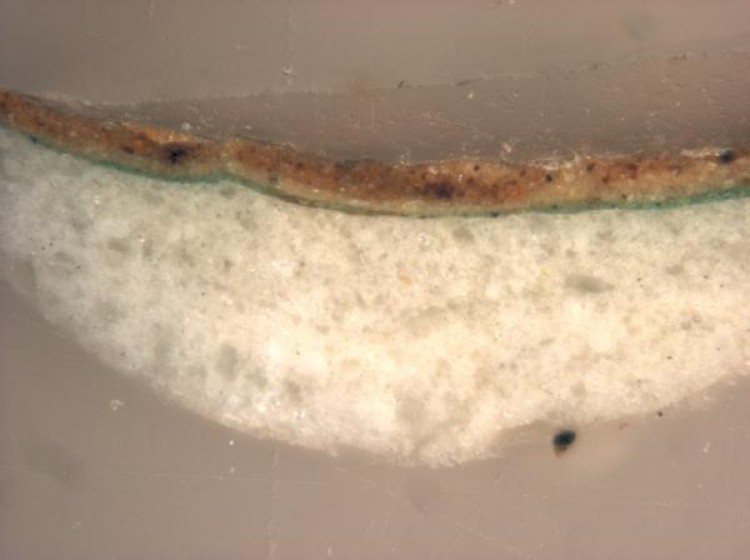

After extensive documentation and examination, samples of paint measuring about 1 mm were sent to the Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) for analysis. Conservation scientists at the CCI prepared the samples and carried out various analyses. Their work helped AGO conservators understand the cause of the instability, and determine how best to fix the painting and care for it in the future.

This image shows one of the CCI’s prepared samples. Analyses indicated that a thick layer of glue had been applied to the canvas. Although this technique was common in commercially prepared canvases of the 19th century, excess glue can be problematic. Glue contracts considerably in dry conditions, which are prevalent in The Grange during the winter months. Yet when humidity increases during the summer, the glue swells as it takes up moisture from the surrounding environment. This cycle of shrinking and swelling led to cracking and separation of the layers of glue in the painting. The CCI analyses also revealed that the ground, or surface, of the painting was poorly bound, resulting in poor adhesion to the adjacent layers.

Consolidation

Once AGO conservators had a better understanding of the source of the problems, they were able to devise a course of action and begin testing to re-secure the paint, a process known as consolidation. Conservator Andrew Ornoch examined the painting through a microscope – testing begins on a very small scale. After testing a variety of materials, conservators chose wax to consolidate the painting.

Molten Wax

Here, Ornoch carefully applies molten wax with a soft brush. After he completed this step, it was then necessary to relax the paint and re-secure it to the surface through the careful application of heat and light pressure. The heated spatula used by Ornoch is specially designed for conservation use, since its temperature can be controlled with great precision. This process was time-consuming, as many areas of the painting required repeated treatment.

Removing Overpaint

Previous retouches and overpaint were visible on the painting. These sections had become discoloured, and appeared as darker patches on the image. The overpaint was removed using specialized mixtures of organic solvents. Microscopes are essential tools in this stage of conservation, which requires careful removal of non-original paint without disturbing the integrity of the original work.

Traditional Gesso

Numerous areas of paint loss were filled with traditional gesso. During this stage, conservators must ensure that the filler does not cover any original paint.

Retouching

The paint losses were retouched using stable conservation materials. Retouches are strictly limited to areas of paint loss or damage.

Varnish

An isolating layer of varnish was applied to saturate and protect the paint. Several additional coats of varnish were sprayed onto the canvas to further saturate the painting.

Before and After

Treatment of the Boulton portrait required more than 540 hours of work. As a result, the portrait was successfully stabilized and its appearance has improved dramatically. The treatment entailed extreme patience and precision, but the countless hours invested in the project by Ornoch and the AGO’s conservation department have clearly paid off. According to Jennifer Rieger: “It’s as if Berthon himself just put on a new coat of varnish.” While the painting has been returned to its original frame, it has also been enclosed in a secondary frame with a sealed back and Plexiglas front, which should help preserve the work for at least another 100 years.