Re-imagining the Enslaved Eighteenth-Century Freedom Seekers as Twenty-First Century Sitters

Charmaine A. Nelson

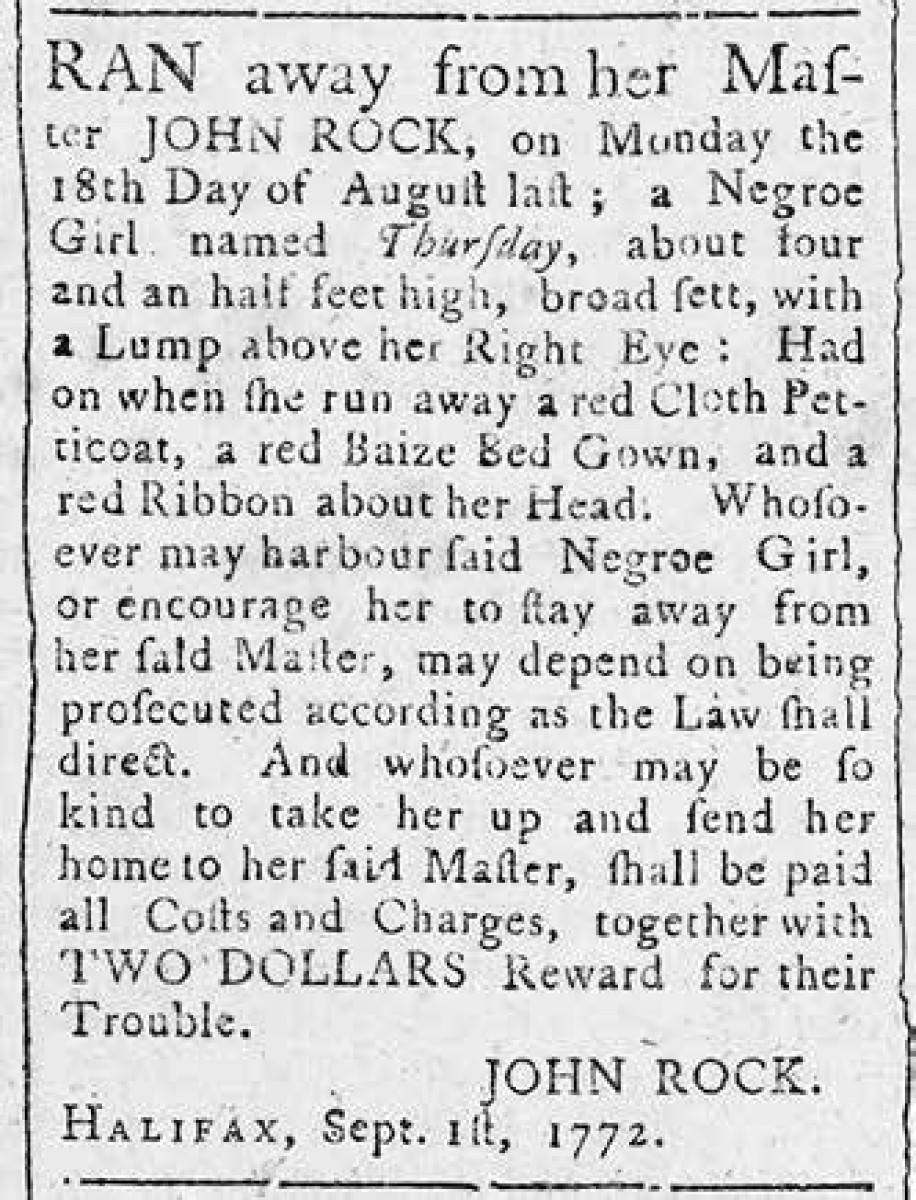

FIG 1 Fugitive notice for Thursday, placed by John Rock of Halifax, in the Nova Scotia Gazette and Weekly Chronicle, September 1, 1772.

Since at least the seventeenth century, Africans arrived in Canada in bondage. Their forcible relocation from Africa, or other parts of the Americas, was facilitated by their designation, first as cargo, and subsequently as chattel; a strategy that excluded them from the category of settler. That these histories—spanning over two hundred years and two empires (British and French)—are overwhelmingly disavowed is a result of Canada’s national myth of racial tolerance and, concomitantly, the profound failures of Canada’s education system. However, it does not take much digging to uncover the lie of our blinkered, heroic, national self-aggrandizement as the territory to which enslaved African Americans fled.¹

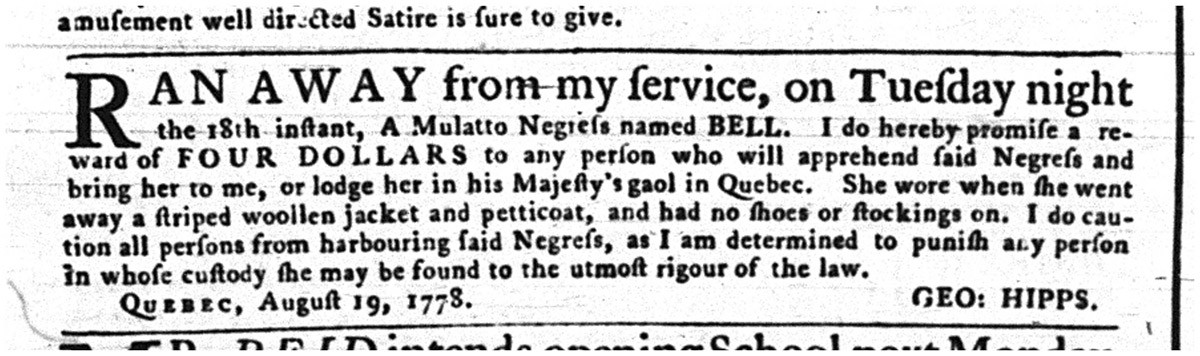

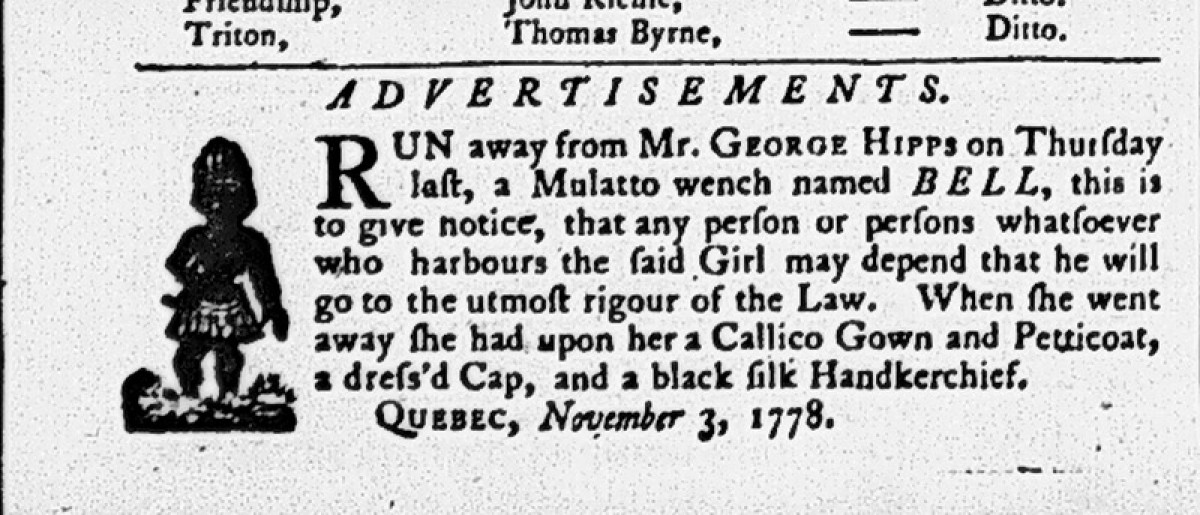

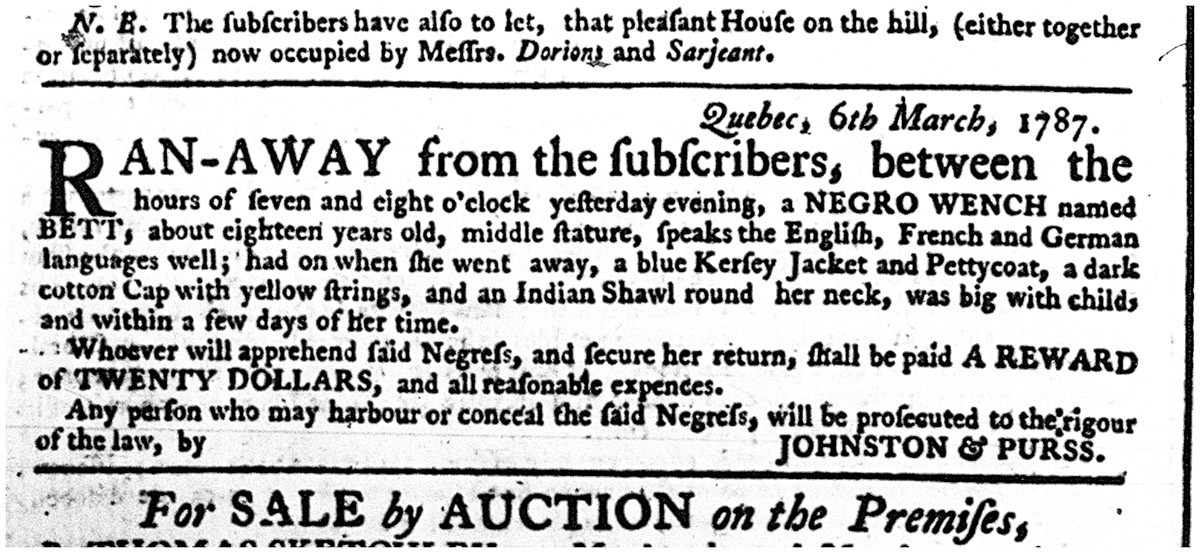

On Tuesday, September 1, 1772, John Rock of Halifax, Nova Scotia, placed a fugitive notice in the Nova-Scotia Gazette and the Weekly Chronicle for an enslaved Black girl known as Thursday (Figure 1). Rock’s notice for Thursday obscenely juxtaposed descriptions of her self-care and beautification practices (the red ribbon worn about her head) with what was almost assuredly evidence of her physical abuse (the lump above her right eye). The fugitive notices placed for Bell and Bett, both of whom briefly escaped captivity in Quebec, also convey something of the specific horrors of female enslavement (Figures 2–4). Bell’s two documented escapes, less than three months apart, attest to the urgency of her desire to flee.2 That she first ran away in August 1778, with “no shoes or stocking on,” and fled again in October 1778, when fall temperatures made escape even more perilous, speaks to her desperation. But the conditions of Bett’s escape were even more dramatic. When the approximately eighteen-year-old Bett escaped on the winter evening of March 7, 1787, the merchants Johnston and Purss described her as “big with child, and within a few days of her time”3 (Figure 4).

FIG 2 Fugitive notice for Bell, placed by Geo. Hipps in the Quebec Gazette, August 20, 1778.

FIG 3 Fugitive notice for Bell, placed by Geo. Hipps in the Quebec Gazette, November 3, 1778.

FIG 4 Fugitive notice for Bett, placed by Johnston and Purss in the Quebec Gazette, March 8, 1787.

Fast-forward to 2017, and Bell and Bett have been re-imagined: Bell as a stunning, caramel-coloured vision in a figure-flattering dress and stiletto heels, her gaze confidently confronting us for daring to interrupt her mid-phone call; and the exquisite seated Bett, eyes concealed behind fashionable dark sunglasses, showing off her beautiful, chocolate-coloured legs beneath her multi-coloured, ruffled skirt (Figures 5 and 6). But what does it mean to re-imagine these eighteenth-century enslaved freedom seekers as poised and beautiful, twenty-first century divas?4 The colonial archive of fugitive slave advertisements (including significant collections in Nova Scotia, Quebec, and Ontario) calls us to understand the retention of African self-care practices within the world of psychic, physical, and social abuse and material deprivation that was Transatlantic slavery. Through their innovative photographic reinterpretations of enslaved Africans in Canada, Camille Turner and Camal Pirbhai exploit this archive to provoke a conversation about Canada’s role in Transatlantic slavery, the stolen potential of our enslaved ancestors, and the resilience of Canada’s diverse African populations. The fugitive or runaway slave advertisement provides for us a window into the lives and worlds of the enslaved. Frequently printed in weekly newspapers alongside other news and advertisements of transatlantic significance, such notices routinely incentivized the public’s cooperation with the offer of rewards and the threat of judicial retribution. Ubiquitous across the Americas, each example was about the recapture of an individual, or individuals, who had fled, and as such, required that their owners share details that illuminated what made the runaways unique, both in manner and appearance.

Research on the enslaved poses several substantial problems for the researcher; not the least among them are the ways in which the colonial nature of the archive occludes the lives of people who were held in bondage. Since the enslaved were considered cargo, commodities, or chattel in economic and legal discourses, white slave owners and their surrogates strategically prohibited them from being recorded in registries, ledgers, and documents, which were used to individualize and humanize whites.

Such advertisements are what Graham White and Shane White have referred to as “the most detailed descriptions of the bodies of enslaved African Americans available.”5 I would argue that their contention also generally applies to the regions of the Americas that practiced the Transatlantic slave trade, particularly places where abolition predated the development of photography.6 Displaced from their homelands and forced to take up the role of un-free labour in the Americas, enslavement severely impeded the ability of Africans to remember their histories, maintain their ethnic specificity, practice their cultures, and care for their bodies. This was strategic on the part of white colonialists and the slave-owning classes, and evident in the immediate implementation of slave practices—like branding and renaming—that were meant to break the enslaved from their sense of individuality, family, and ancestry.7 Indeed, as Marcus Wood contends, “Slavery, as a legal and economic phenomenon, was premised upon the denial of personality, and of a personal history, to the slave.”8 Furthermore, ruling-class whites deliberately developed the colonial archive in ways that allowed Africans to enter almost always as the objects or “stock” owned by another, and therefore as partial and incomplete entries. This disturbing fact— that the most detailed representations of the enslaved were produced by their owners—provokes a confrontation with the archive, not as an objective or neutral container of facts and information, but as a site through which the elite secured their power by determining who could be represented and in what fashion.

Camal Pirbhai and Camille Turner, Bell (Wanted Series)

Camal Pirbhai and Camille Turner, Bett (Wanted Series)

Reading the Runaway

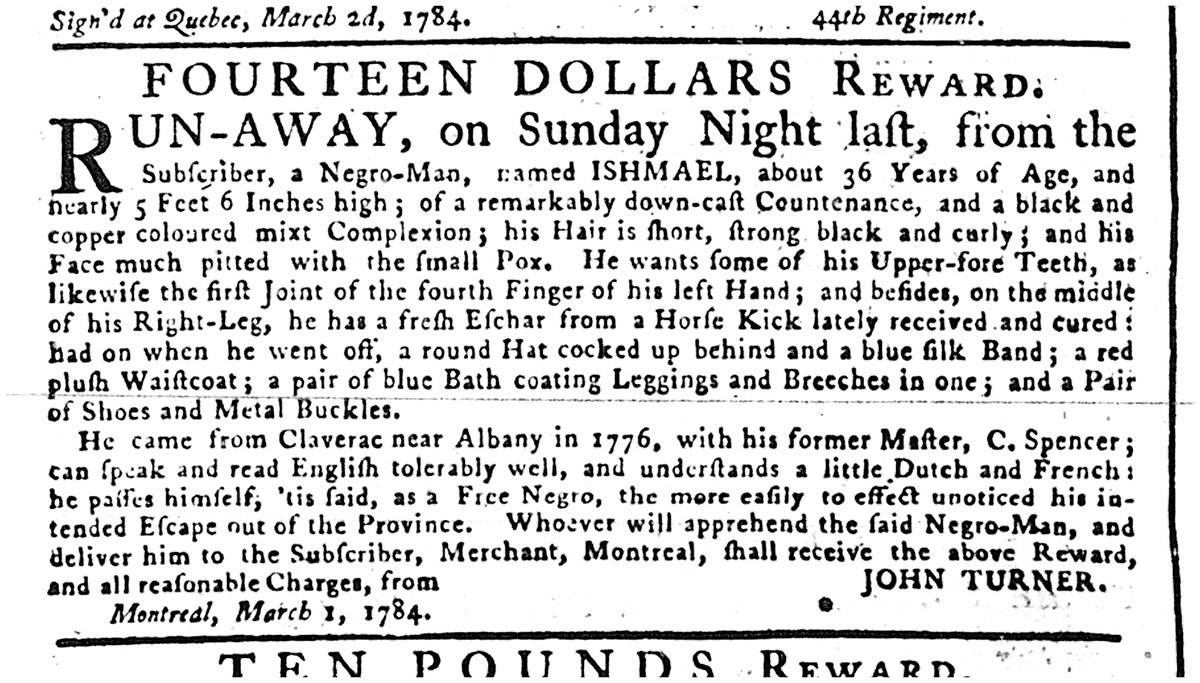

FOURTEEN DOLLARS Reward

RUN-AWAY, on Sunday Night last [28 Feb.] . . . a Negro-Man, named ISHMAEL, about 36 Years of Age, and nearly 5 Feet 6 Inches high . . . his Face much pitted with the small Pox. He wants some of his Upper-fore Teeth, as likewise the first Joint of the fourth Finger of his left Hand; and besides, on the middle of his Right-Leg, he has a fresh Eschar from a Horse Kick lately received and cured.9

FIG 7 Fugitive notice for Ishmael, placed by John Turner in the Quebec Gazette, March 11, 1784.

Ishmael, twice represented by Turner and Pirbhai, ran away from the Quebec City merchant John Turner Sr. at least three times: in July 1779, March 1784, and June 1788 (Figure 7). Re-imagined as a dignified modern-day dandy (Figure 8) and a dignified cape-wearing gentleman (Figure 9), his scarred, marked, disabled, and no doubt abused body has been represented as that of self-assured, confident men. While John Turner described Ishmael as possessing a “black and copper coloured mixt Complexion,” the modern-day Ishmaels emerge in two decidedly distinct hues—a move that challenges the authority with which whites laid claim to a knowledge of black bodies.10 Gone is the “old Hat bedawbed with white Paint” (1779) and the pox-marked face.11 Instead, the twenty-first-century Ishmaels exude confidence as both composure and self-possession. While the most obvious glimpse of the original eighteenth-century Ishmael’s ability to take control of his appearance arguably resides in the change in John Turner’s description of his hairstyle—from “wears his own Hair which is black, long and curly” (1779),12 to “his Hair is short, strong black and curly” (1784),13 and finally to “black short curled hair” (1788)—the portraits of the re-imagined Ishmaels leave no doubt about who controls their likenesses.14 Although Turner and Pirbhai are staging our epic re-encounters with enslaved freedom fighters, their fashionable, confident namesakes appear to have more in common with models in contemporary fashion magazines than with the enslaved people who navigated what Trevor Burnard has called “radical uncertainty.”15 The power of this potential reincarnation is that it allows us to think not only about what John Turner stole from Ishmael (his labour, years of his life, his access to self-determination), and how John Turner imagined and wanted to see Ishmael, but also how Ishmael, liberated from bondage, may have imagined and represented himself.

Camille Turner and Camal Pirbhai, Ishmael1 (Wanted Series)

Camal Pirbhai and Camille Turner, Ishmael2 (Wanted Series)

Fugitive Slave Advertisements as Portraits

FIG 10 George Theodore Berthon, Portrait of William Henry Boulton, 1846. Oil on canvas, 240.5 x 147.5 cm. Collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario, The Goldwin Smith Collection, GS111.

What is called for is a rereading of fugitive slave advertisements not as mere texts but as portraits, however questionable, that function primarily through vision. However, the reconceptualization of fugitive slave advertisements as portraits of the enslaved is not a seamless fit for several reasons. First, while traditional “high” art portraiture—like that produced in marble or oil paint—was the end-product of a contract between a patron and an artist for a flattering likeness, the representations of enslaved fugitives generated by slave owners were designed to normalize slavery and to criminalize the enslaved for what Marcus Wood has termed “an act of theft, albeit a paradoxical self-theft”16 (Figure 10). Second, while in the traditional relationship the sitter and the patron were often one and the same, with fugitive notices the slave owner was the patron and creator of the notice, and the sitter was an unwilling participant in their representation. Third, while the artistic term for the represented subject in a portrait—the sitter—expresses the stillness required in the actual process of capturing a human likeness, a fugitive’s escape was characterized by their self-directed motion, something that was literally coded as illegal under colonial law. Therefore, the portrait of the enslaved person that a fugitive slave advertisement captured was not of a stationary person—a sitter—but instead, of a person in motion, a runner.

Finally, since a fugitive’s likeness was published against their will, these portraits were “stolen” and unauthorized. Yet they were also “fugitive” in the sense that they were elusive and often highly false images. They were false in the sense that slave owners deliberately vilified the character of the enslaved in the advertisements they placed, and could often not comprehend or accurately describe the African cultural practices of the enslaved. Furthermore, the commonality of fugitive tactics—like altering one’s appearance or changing clothing to “pass” as another social group (mainly free people) in an age when most poor people had only one set of clothing—meant that the enslaved often did not precisely match their descriptions. The medium of these printed portraits was text, as opposed to images, but the words were often strategically deployed with the goal of creating a mental image of the enslaved. Besides the height, weight, and clothing of the fugitive, such notices regularly recounted bodily marks. Ishmael is a case in point. The legalization of corporal punishment within colonial law meant that the bodies of the enslaved were commonly riddled with signs of violence. But the exposure of slave-owner violence in the description of the enslaved person’s injured and tortured body—seen as necessary to the economic ends of the advertisement—signalled the moment in which the fugitive notice became a weapon against the slave-owning classes. As Wood explains, “the runaway emerges as a metaphor for white moral failure.”18

Conclusion

Returning to my original question, what is the meaning of such a deliberate re-imagination? Decked out in the most fashionable clothing, beautiful, charismatic, and self-possessed, these re-imagined subjects are no longer oppressed, frightened, hunted, and terrorized. They exude confidence, delight in frivolity, and embrace luxury—things not afforded their namesakes. By insisting that Bell, Bett, and Ishmael were not slaves, but enslaved—not possessions, but humans—we can see in their desire for freedom, as documented in their eighteenth-century fugitive notices, their heroism. This heroism resides not only in their literal quests for freedom but in their insistence that their bodies were their own, to be dressed (Thursday’s red ribbon), styled, coiffed (Ishmael’s cropped hair), and beautified as they—and not the slave owners—saw fit. As Canadians reflect on the 150th anniversary of our nation, it behooves us to challenge the customary image of a homogeneously white Canada, one that strategically excludes the memory of Canadian participation in Transatlantic slavery and erases the centuries-long presence of people of African descent. Through the re-imagining of Bell, Bett, Ishmael, and other valiant freedom seekers, Camille Turner and Camal Pirbhai challenge us to think anew about the tremendous importance of integrating the memory and histories of Black Canada into our national narrative.

Dr. Charmaine A. Nelson holds a Ph.D. in Art History from the University of Manchester. A professor at McGill University, she lives in Montreal. Her book Slavery, Geography, and Empire in Nineteenth-Century Marine Landscapes of Montreal and Jamaica was published in 2016.

NOTES