ICYMI: Diasporic connections

August 7 is your last day to check out Toronto-based filmmaker Esery Mondesir’s first AGO exhibition – Esery Mondesir: We Have Found Each Other – delving into the rich complexity of the Haitian diaspora.

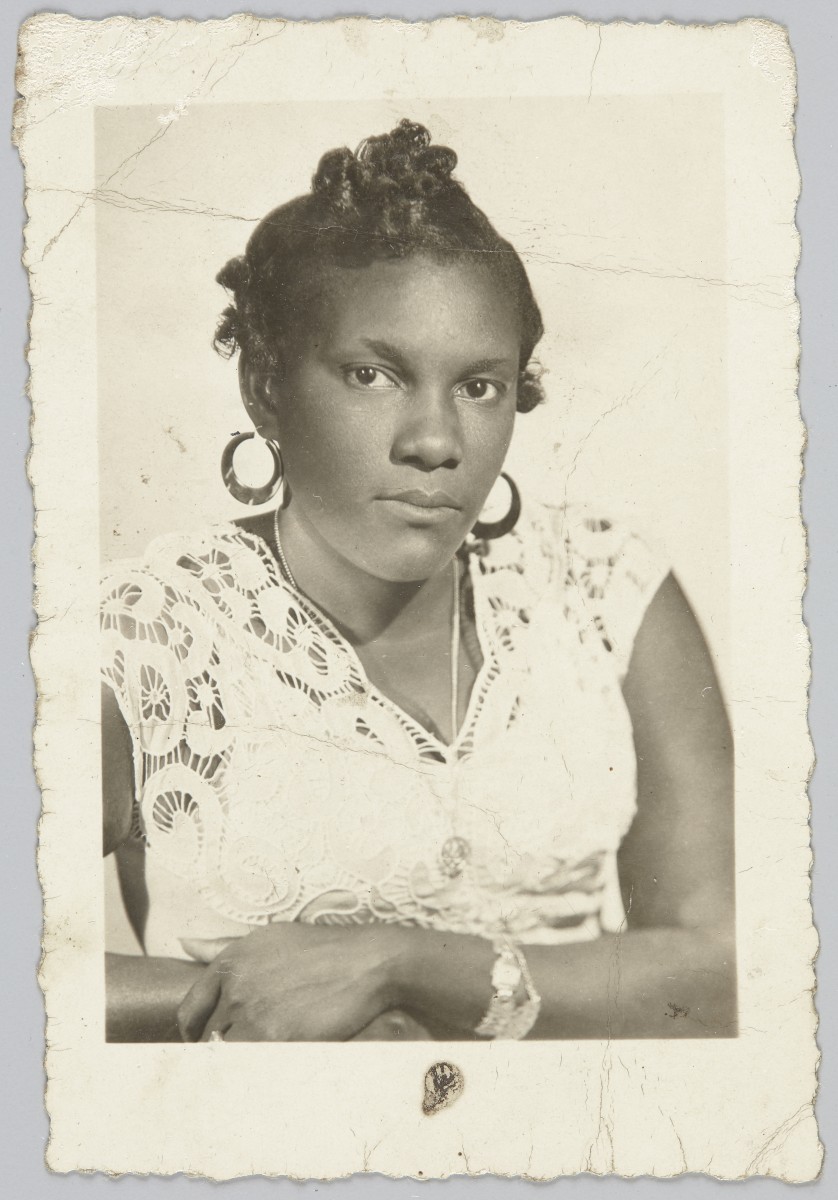

Esery Mondesir. Film still from Katherine, 2019. Hand-processed 16mm film transferred to HD video, duration 3 min 31 sec, looping. Courtesy of the artist. © Esery Mondesir

Toronto-based filmmaker Esery Mondesir’s work is an exploration of the Haitian Diaspora. He combs through personal archives, institutional collections, music and oral histories to highlight unique connections between descendants of Haiti, spanning multiple regions and generations. His new AGO exhibition, Esery Mondesir: We Have Found Each Other, centres the cultural and migratory relationship between Haiti and Cuba.

The centrepiece of the exhibition – Katherine (2019) – is a film-based work in which Mondesir creates an homage to African-American dancer and activist Katherine Dunham (1909–2006). In footage from 1962 – which Mondesir found online and processed through analog and digital means to give it its distinctive and dreamy look – Dunham is seen dancing outside her home in Martissant, Port-au-Prince, Haiti – Mondesir’s childhood neighbourhood. The audio in Katherine is the music of the Cuban-Haitian performance troupe, Grupo Misterios del Vodú, recorded live by Mondesir in 2014.

As an accompaniment to the film, Mondesir has included 10 passport photographs, each depicting Haitian women living and/or working in Cuba in the 1950s and ‘60s. On loan from the Montreal-based Centre International de Documentation et d’Information Haïtienne, Caribéenne et Afro-canadienne (CIDIHCA), the photographs reflect the migratory history of Haitians relocating to Cuba for economic reasons – specifically highlighting the lesser documented narratives of women.

We connected with Mondesir to find out more about the Haitian diaspora, Katherine Dunham and his unique style of filmmaking.

AGOinsider: You’ve described your art practice as “a search for kinship”. Can you elaborate on the meaning of that description?

Mondesir: “Sidney Poitier was Haitian” was essentially the headlines coming through my social media feeds when the iconic African-American actor died last week. I am not interested in verifying this information. Still, I am always fascinated by the nationalist impulse to claim or re-claim kinship with important historical figures — whether that impulse comes from Canadians, Haitians or other national configurations.

In a way, I am searching for the same type of relations to better understand concepts of creolization, roots and (dis)filiation — in a Glissantian sense. But that exploration necessarily raises questions about marginality, resistance and justice, for me, given my position in the world.

On January 1st,1804, formerly enslaved Africans in Haiti broke their chains and changed the course of world history in the process. Their radical imagination created unprecedented turbulence for the power structures of the colonial world. Yet, “no one wanted to be Haitians,” my friend Silverio told me, speaking of his experience growing up in Eastern Cuba in the 1950s. How can we reconcile the realities of contemporary Haiti and Haitians with the hope for and the possibility of liberation that 1804 represents for us All? How would notions of justice inform the creation of the One World in Relation, le Tout-Monde that Edouard Glissant imagined?

AGOinsider: Can you share some of your thought processes when forming the concept of Katherine? What are some of the reasons you paired footage of Katherine Mary Dunham with the sounds of Grupo Misterios del Vodu?

Mondesir: El Grupo Misterios de Vodú is a group of Cubans of Haitian descent I met over ten years ago in San Francisco de Paula, a neighbourhood in the outskirts of La Havana. The group's musicians, dancers and administrators are from the same family, the Gardes, whose father arrived in Eastern Cuba from Southern Haiti as a 12-year-old boy in 1922. When I met them, the Gardes siblings had never set foot outside of Cuba, but everyone in the neighbourhood called them los Haitianos, the Haitians. They also call themselves so, although that identity keeps them in the margins of mainstream cubanness, cubanidad. Being around the Gardes, you have the sense that what they’re holding dear in their hearts is also precious and sacred.

Katherine Dunham was a Black-American scholar and choreographer with mixed roots too. Her mother was a French-Canadian, and her father, a Black-American. In 1936, Dunham travelled to Haïti and immersed herself in many local communities to study and embody Black dance and rituals that she would later articulate through a creole dance form, namely the Dunham Technique.

This pairing is as much about routes as it is about roots. I am interested in this dual movement outward/toward Haiti, as a place, an idea and an ideal. At the same time, I want to try and locate Dunham’s gesture and the Gardes presence in Cuba within a discourse around rhizomatic roots.

AGOinsider: How did Haitian film director Frantz Voltaire play a role in this project? What can you tell us about the origin of the passport photos?

Mondesir: The photographs that complement Katherine in the exhibition were “reclaimed” from a street-corner dumpster in Havana, Cuba, by Montreal-based scholar and filmmaker Frantz Voltaire. We don’t know much about the folks represented in the photographs, but we know they were Haitian nationals who migrated to Cuba around the 1950s. The presence of Haitians and other Caribbean people in Cuba, mainly as agricultural workers, is well documented. This selection of Voltaire’s collection explicitly emphasizes women's presence in the trans-Caribbean migration story. At the same time, though, I want to reflect on the significance of Voltaire's gesture. I imagine him spotting these photographs in the trash and saying, “these are mine, my people,” just like other Haitians on social media were saying about Sydney Poitier this week, except that none of these women were famous.

AGOinsider: What is next for you? Do you have any upcoming projects, exhibitions or works in progress you are excited about?

Mondesir: There are many more connections to explore and, maybe, re-establish. I cannot wait to be able to get on the road again.

Check out Esery Mondesir: We Have Found Each Other on view at the AGO now before it closes tomorrow (August 4). Stay tuned to the AGOinsider for more art news from the AGO and beyond.