ICYMI: A “Freeman of Color”

Discover Robert Duncanson, a pioneering African-American artist whose work is represented by three paintings in the AGO Collection.

William Notman, Robert S Duncanson, 1864, Notman Archives, McCord Museum, McGill University, Montreal

By Kenneth Brummel, Associate Curator of Modern Art, AGO

On May 30, 1861, the Daily Cincinnati Gazette named Robert Seldon Duncanson the “best landscape painter in the west.” The son of a Black tradesman, Duncanson, a “freeman of color,” was born in Fayette, New York, in 1821. Learning the family trades of carpentry and house painting during his childhood in Monroe, Michigan, he moved to Cincinnati, Ohio in 1840 with the goal of becoming an artist. In addition to befriending Hudson River School landscape painters Worthington Whittredge (American, 1820 -1910) and William L. Sontag (1822-1900), Duncanson during his early years in Cincinnati also secured important commissions that helped launch his career. The eight murals he completed from 1850 to 1852 in the entry hall of the home of Nicholas Longworth, a prominent horticulturalist whose house is now part of the Taft Museum of Art, solidified his status as one of Cincinnati’s leading painters.

Although Duncanson at the outbreak of the American Civil War (1861-1864) lived in an area of Cincinnati known for its abolitionist sympathies, he decided to leave the border city for safer and more stable ground in Minnesota in autumn 1862. Worried a few months later that the Union Army would lose the Confederacy’s “War of the Rebellion,” Duncanson fled Minnesota and entered Canada in 1863, ultimately settling in Montréal, where he lived until 1865. During his two-year stint in Québec, Duncanson taught the Canadian painter Allan Edson (1846-1888). He also had an impact on the work of John Fraser (Canadian, 1838-1898) and Otto Jacobi (Canadian, 1812-1901), revolutionizing the tradition of Canadian landscape painting in ways that are still visible today.

It was during Duncanson’s self-imposed exile in Canada when he painted the three works that are now in the AGO Collection. In On the Road to Beauport, Near Québec (1863), Duncanson, utilizing the formal strategies of the Hudson River School, specifically those codified by Thomas Cole (American, 1801-1848), creates a harmonious composition that coheres into a balanced, unified whole. Depicting the changing, autumn leaves with touches of red, yellow, orange and ochre, Duncanson generates a rhythm of alternating dark and light colour values across the foreground plane that highlights the painting’s overall symmetry while also directing the viewer’s attention to the monumental copse of coniferous trees at the canvas's center.

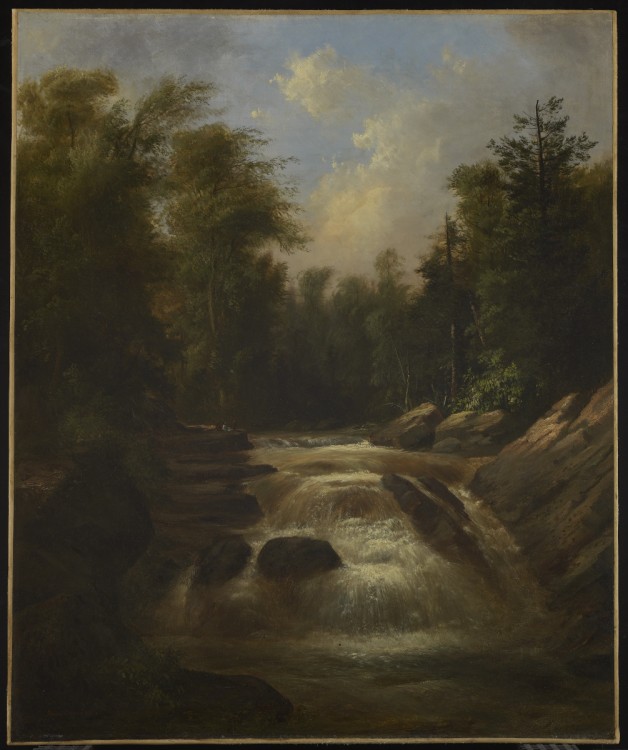

Duncanson’s approach to landscape in River with Rapids (circa 1864) is somewhat different. Placing this painting’s most expressive component, the trapezoid of cascading froths, at lower center, he transforms what at first appears to be an intimate view of nature into a representation of the sublime by situating three diminutive figures on a large rock at the head of the river’s rapids. Dwarfed by the towering trees of the surrounding forest, these figures are also upstaged by the fluvial landscape that unfolds around and below them.

Duncanson explores the sublime more fully and more personally in his Seascape of 1864. As the light of dawn separates the sky from the turbulent ocean below, a small ship to the right of the furthest outcropping rushes toward the luminous rays on the horizon. Safely ensconced in Canada in 1864, Duncanson, when painting this view of the Atlantic, must have been meditating on all the violence and tumult that drove him away from the U.S. two years earlier. Executing Seascape before sailing to Great Britain in 1865, Duncanson, I want to believe, was also imagining a crossing of the Atlantic that would lead to a promised land of self-determination and freedom and not to the dehumanizing hell of hatred and enslavement that he and others tried all too hard to escape and avoid.

In the winter of 1866-1867, Duncanson returned to Cincinnati an internationally acclaimed artist. A writer for The Art Journal in London even called him a “master” of the genre of landscape painting. It is a fitting title for a “freeman of color” who in the 1860s refused to allow anti-Black racism and the threats of the Confederacy to compromise him, his art and his aesthetic autonomy.

Keep up to date with all your AGO news and updates with the AGOinsider. Sign up today and have stories like these delivered straight to your inbox every week.