Lucite: A see-through tour

In this, the first in a new occasional series exploring artistic materials, we get up close with a transparent wonder.

Installation view, showing Lucite case. Shuvinai Ashoona. Composition (Cube), 2009. coloured pencil, black porous point pen on paper, Overall: 41.9 x 39.4 x 39.4 cm. Purchased with the assistance of the Joan Chalmers Inuit Art Purchase Fund, 2009. © Shuvinai Ashoona / Reproduced with the permission of Dorset Fine Arts. 2009/92

Lightweight. See-through. Bendable when heated. Recyclable. When chemists working for the DuPont Company patented a new acrylic resin formula in 1937, it was the latest in a wave of synthetic materials invented to replace glass. Whether called Plexiglas, Perspex or Lucite, these brand name acrylic resins replaced the glass canopies in fighter planes during WWII, and have since been turned into everything from kitchen bowls to tail lights. Today, these materials are more in demand than ever, shielding essential workers in the global fight against COVID-19. But Lucite as an artistic medium? In search of material evidence, we took a physically-distanced tour through the AGO.

First stop, the Gallery's Conservation lab, for a lesson in chemistry. “Lucite,” says AGO’s conservator of contemporary art Sherry Phillips, “is just one proprietary name for high-quality acrylic, made of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA). Acrylic chemistry can be found in a lot of everyday materials – paints, varnishes, solids. Here at the AGO, we use it to build cases and mounts for artwork, to frame artworks and for shielding in the visitor services area.”

Describing acrylic as a durable material, it is, Phillips says, one that “accepts dyes well, can be made UV resistant, has good optical properties and a high refractive index, but scratches easily. It has poor impact resistance, limited heat resistance, can crack under load, and has limited chemical resistance. Our treatment approach to an artwork made of PMMA has to take all this into consideration so we don't cause more damage.”

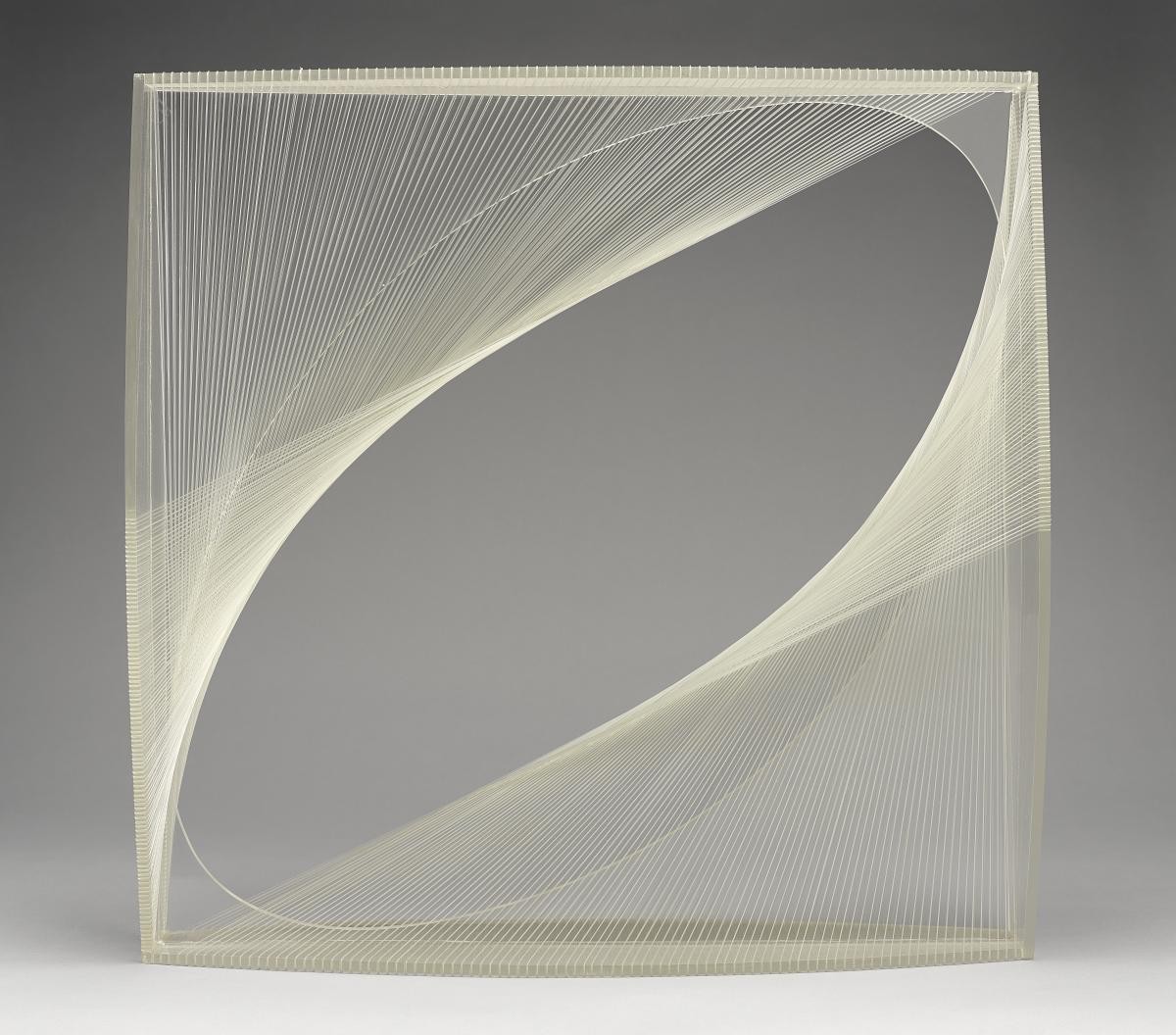

Descending from the Conservation lab, we make a quick stop on Level 4 to admire a new acrylic case. The brainchild of AGO exhibition designer Theodora Doulamis and cabinetmaker Roland Hardy, the case was custom designed to display Shuvinai Ashoona’s 3-D artwork from 2009, Composition (Cube). It features a five-sided acrylic cover, mounted atop a wooden base.

“The unique appearance of this case makes it appear like it is an acrylic cube which contains the artwork inside, but in fact it is an illusion created by the design and carpentry,” says Doulamis. Ashoona’s artwork is actually sitting on a separate sheet of acrylic, or what Hardy calls “a deck. The five acrylic sheets that cover the artwork,” he adds, “were joined by the manufacturer ‒ they often use what is called liquid welding, where a liquid bonds the sheets as they dry."

The decision to build and design the case this way, says Doulamis, comes down to many factors. “Research had to be done by looking at various manufacturer’s specifications and test studies to see how the material performed under stress forces that would come from the weight of the artwork and its handling.”

In the AGO’s galleries of modern art on Level 1, Lucite provides another kind of container – a container for a dynamic, negative space. Russian modernist sculptor Naum Gabo (1890-1977) began making art with Lucite and other acrylics in 1937. Rejecting the traditional materials of sculpture such as bronze, Gabo used Lucite and other transparent, lightweight substances to construct objects that could incorporate the material and the immaterial, so as to embody the universal and the infinite. His Linear Construction in Space No. 1 (ca. 1945–46) features a clear acrylic square frame bound elegantly in thin nylon monofilament strings. Together they create an illusion of shifting planes and continuous depth as one’s eye moves along the luminous surfaces of the sculpture.

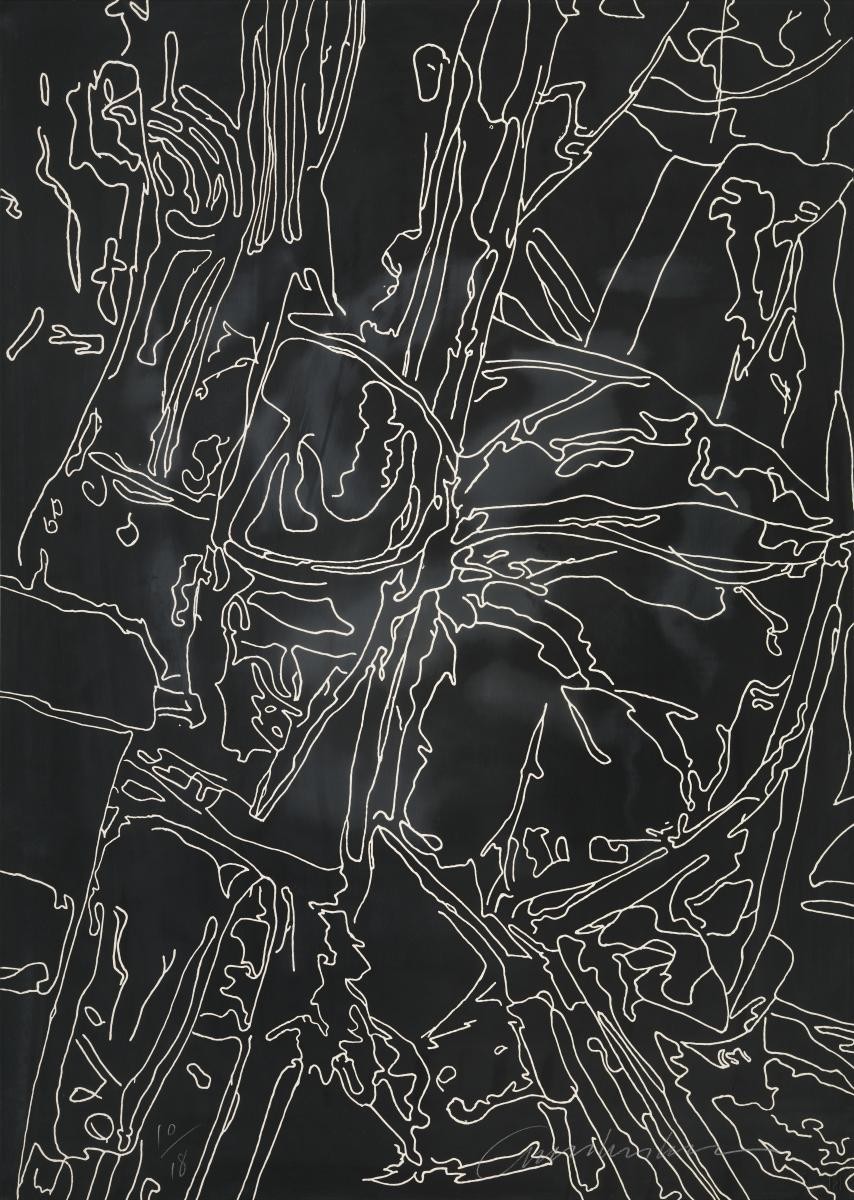

Downstairs in the AGO vaults, two relief prints by American artist John Chamberlain (1927-2011), generously donated to the AGO in 2020, show a different side of Lucite. Hog on Ice (1989) and Trusted Value (1989) were created as part of a portfolio of six monoprints, entitled the Crushed hors d’oeuvres, made by Chamberlain with the assistance of Gordan Novak, a Canadian printmaker and publisher, previously based in Toronto. Chamberlain’s decision to print directly from the incised Lucite plates was a spontaneous one, Novak recalls.

“In 1984, I traveled to his studio in Sarasota, Florida with two of my studio printers to start the monoprints project...There was a large pile of shiny chrome car bumpers by the window. In the late afternoon, when we took a first cognac break, the late day sun created miracle reflections on the pile. John took one of the plastic sheets that we were using in making the plates for monoprints and had drawn line drawings inspired by the view. Immediately, he incised the lines with an electric tool. Intention was to print it in black as traditional engraving. After proofing, John did not like the proof. “It is too white,” he said. So, we proofed it very black, by rolling the black ink as a surface roll leaving the paper white where the lines were engraved. Magic! “That is it,” John said, and the next day made five more drawings. Crushed hors d’oeuvres were kind of appetizers for several series of large monoprints that followed.”

Now nearing the entrance of the AGO, we’re passing the Welcome Desk, encased in the clear Lucite panels, added last summer to ensure the health and safety of visitors and staff. Having proven that you can build with it, look through it, and carve into it, the only question on this tour remains, can you bend it?

The answer, as we walk into shopAGO, is a very pretty yes. In fact, Toronto-based jewellery designer Corey Moranis has developed an international following for her Lucite designs. “Lucite is both rigid and plastic at the same time, containing a memory of its previous liquid phase like a frozen waterfall. It seems to possess its own inner light. It’s there, but it’s not,” says Moranis.

Working with Lucite as a medium presents its own challenges, though. “There are many stages in the process and there are no shortcuts,” Moranis adds. “It’s clear, so you have to have a really trained, focused eye to catch and fix imperfections.” She uses heat-bending to curve the knots, loops and twists that ripple through her pieces—straight lines or harsh angles are rare.

Has the 1930s dream of better living through plastic come true? Perhaps not. But have acrylic resins made the world safer? Yes. More artful? Definitely. Proving that where there’s a material, there’s an artful way to use it, we conclude our brief tour of the AGO.

Stay tuned for future material explorations.