A mindful transformation

A new AGO exhibition exploring the medieval origins of European meditation opens July 21, featuring works from the Thomson Collection of Art.

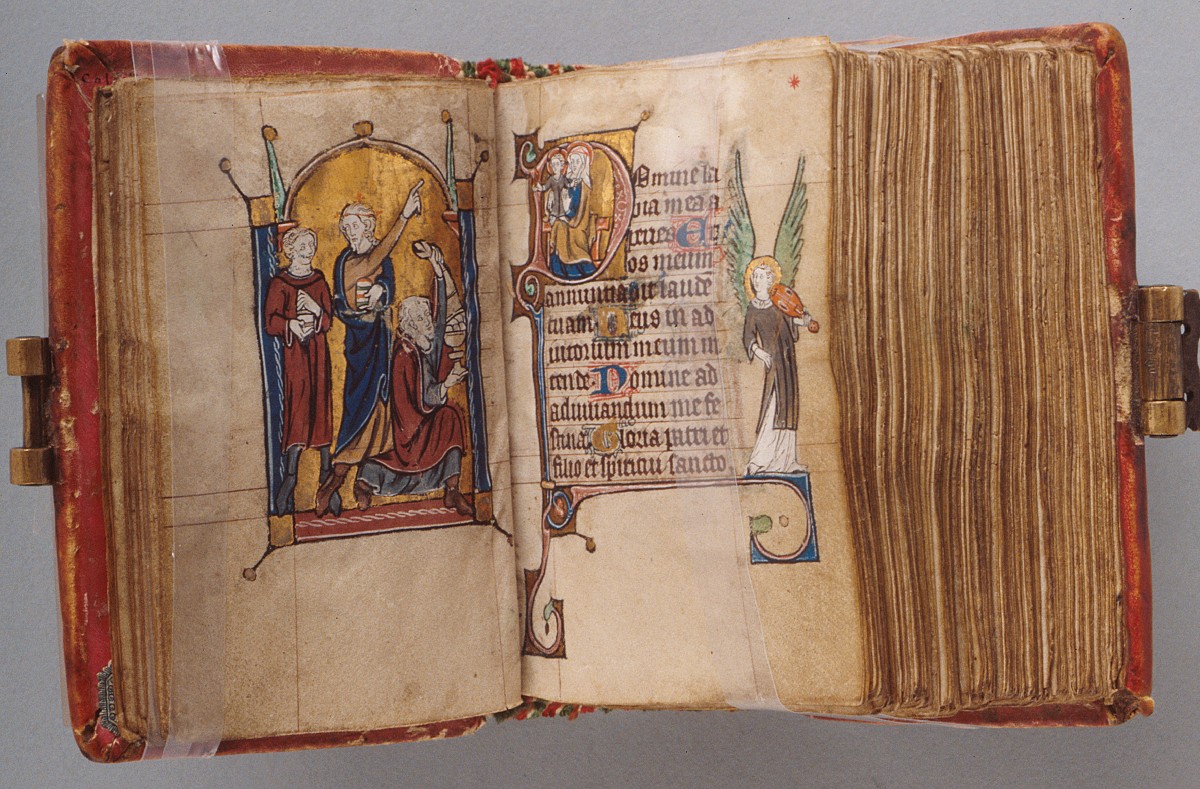

Belgian (Liège). Book of Hours, 1310-1320. Tempera, gold, ink on parchment, Overall: 11.3 x 9.7 x 3.6 cm. The Thomson Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario. © Art Gallery of Ontario AGOID.29411

The AGO re-opens to the public on July 21 with an exciting and dynamic group of exhibitions that are sure to make your first visit back a memorable one. Highlighting selected works from the Thomson Collection of European Art through a fascinating lens, Meditation and the Medieval Mind zeros in on medieval Christian culture.

Curated by Adam Harris Levine, AGO Assistant Curator, European Art, the exhibition explores a moment of major transition in Christian religious practice in which a new focus on individual prayer and meditation ritual emerged. Personal meditation manuscripts, prayer beads and miniature ivory sculptures are among the meticulously detailed objects Levine has included. Though centuries old, these sacred objects carry contemporary relevance, as reflected in the present-day popularity of mindfulness exercises.

For more curatorial insight, we spoke with Adam Harris Levine about the exhibition and the unique history it showcases.

AGOinsider: What would you describe as the main factors behind the 13th century shift in Christian religious practices in Europe? Why were people becoming more interested in private meditation?

Levine: The late 1200s was a time of cultural, intellectual and social change in Europe. This is a really cerebral moment in European history: many people moved from the countryside to growing cities, universities grew quickly, and a growing merchant class gained economic agency. All of this coincided with new trends in Christian devotion. Saint Dominic invented the rosary, a tool for private prayer, in the 1200s, and it gained popularity fast. Much of this private devotion was affective, empathetic responses to the most dramatic narrative moments of the Christian Bible, like Christ’s suffering at the end of his life, or the Virgin Mary’s loss and mourning. The art objects made as part of this movement helped their users to visualize these moments, and facilitated personal, emotional responses.

There is music in the exhibition, performed by incredible musicians Anne Azéma and the Boston Camerata, which was first composed in northern Europe between 1250 and 1550. The music reflects thenew trends in religious practice, especially Christianity’s new devotion to the Virgin Mary.

AGOinsider: Many of the religious manuscripts from this era were produced in monasteries. Can you elaborate on what the production process was like for a monk working as a copyist?

Levine: Most medieval books were made in two contexts: in religious communities, with monks and nuns in workshops called scriptoria, or by professional scribes who made their living in cities or at royal courts. In either case, the process started with acquiring parchment, animal hides stretched and dried and cut into rectangular pages. The artists who made the manuscripts’ miniature paintings, called illuminations, performed different tasks from those who copied the actual texts.

Parchment was an expensive commodity, so medieval books were valuable and costly, and they could become increasingly precious with the addition of illuminations and even gold and silver leaf.

AGOinsider: Can you share some of your process for selecting pieces from the Thomson Collection to include in this exhibition? What criteria did you use?

Levine: A key premise of the exhibition is that an effective meditation tool catches and keeps your attention, so I chose objects that have always done that for me. Many are tiny, delicate objects that make you bend down and squint, and maybe even hold your breath while you’re handling them. I wanted objects that are delicate, moving, and that contain whole worlds inside them. Many of the objects in the exhibition have moving parts, or pages to turn, and these devices allow the user to spend even more time in meditation: different variations on a theme, basically. For instance, there is a functional, miniature book with scenes from the life of Christ, made from gold and silver that operates on a brilliant hinge system, so you can carefully turn the pages and ponder the images on each of them.

AGOinsider: Do you have a favourite piece from the exhibition? What makes it special to you?

Levine: I love everything in the exhibition, but I was especially excited to display the Commentary on the Book of Job, made in the late 1390s at the court in Prague. The illuminated manuscript is notable for a number of reasons: unusually, it’s assembled from sections made on parchment and sections made from paper at a time when paper was exceedingly rare; it’s frankly massive, and it was bound with a beautiful animal skin wrap to protect its pages when closed. We gave the Commentary its own case, so we could display some of its gorgeous illuminations, but also unfurl the wrap and show our visitors how the book sort of sprawls invitingly across a reader’s table. It gives you a sense of just how different the medieval relationship to handmade manuscripts was from our engagement with flimsy, inexpensively produced paperbacks.

Don’t miss Meditation and the Medieval Mind on view in the Carol Tanenbaum Gallery, Gallery 116.