To the moon and back

James Nasmyth, photographer, Mercator and Campanus Plate XV from The Moon: Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite, 1874. Woodburytype, Image: 17.7 x 13.5 cm, Sheet: 27 x 20.4 cm, Mat: 45.7 x 35.6 cm. Purchase, with funds donated by Stephen Brown and Brenda Woods, 2012. 2011/288 © 2018 Art Gallery of Ontario.

Tomorrow is a celestial triplet – a blue moon, supermoon and a lunar eclipse. With the moon on our minds, it’s the perfect time to feature some of our beautiful photographs of the moon.

Our fascination with the moon and galaxies did not begin with a man walking on the moon. For thousands of years, astronomers have tried to understand the mysteries of the universe. But images of the moon only began to circulate widely with the arrival of photography. In the late 1800s, photographers and astronomers used creative methods to capture the splendour of Earth’s orbiting sidekick. Three of these hybrid artist/astronomers, James Nasmyth, Maurice Loewy and Pierre Henri Puiseux, are currently on view in the AGO’s Odette Gallery.

In 1874, Nasmyth, a Scottish mechanical engineer and amateur astronomer, co-created a publication called The Moon: Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite. Photographic technology was not yet advanced enough to capture direct images of the moon. How did Nasmyth create intricate close-up shots of the moon’s surface? His process might surprise you.

First, he used a telescope to look closely at the surface of the moon and created large format drawings based on his observations. Then he used the drawings as a blueprint to create three-dimensional plaster models. Finally, Nasmyth strongly lit his lunar models to highlight various craters and details. Only then did he photograph them. Nasmyth’s labour-intensive method paid off, and many of the individual pages of his photographic plates (we have four on view) were sold individually.

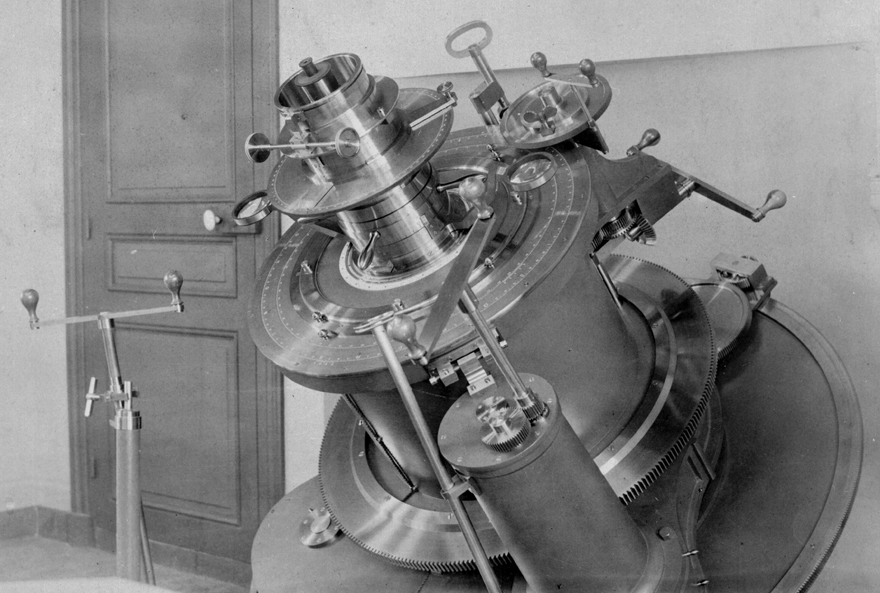

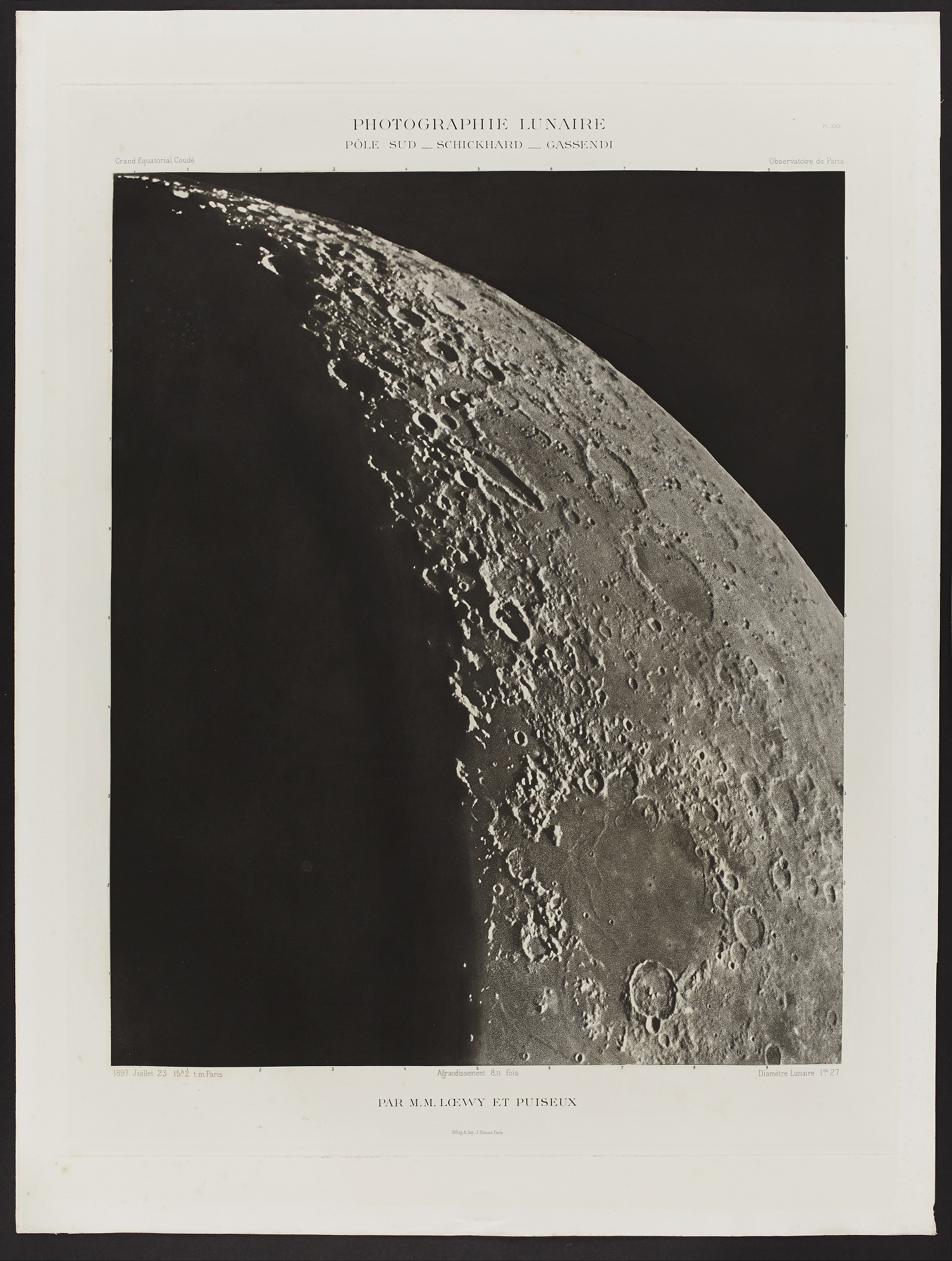

By the 1890s, technology improved significantly. In 1896, astronomers Loewy and Puiseux set out to photograph the surface of the moon. Loewy invented a large, specialized telescope (pictured above) for the Paris Observatory that allowed for the production of high-quality photographs. Despite this advancement, lunar photography required perfect weather conditions. With only 50 to 60 clear nights a year, the project took 14 years to complete. Loewy and Puiseux’s Atlas photographique de la lune remained the primary reference for lunar photographs until the 1970s, a section of which you can also see on display in the AGO’s Odette Gallery.

When it comes to capturing the relationship between science and art, photography is an ideal medium and the moon is the perfect, albeit tricky, model. Get ready for tomorrow’s lunar lunacy by visiting these amazing images of our celestial neighbour.

Are you an AGOinsider yet? If not, sign up to have stories like these delivered straight to your inbox every week.