John William Waterhouse, "'I am half sick of shadows,' said The Lady of Shalott" (Alfred, Lord Tennyson, The Lady of Shalott, Part II), 1915. Oil on canvas, 100.3 x 73.7 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift of Mrs. Philip B. Jackson, 1971. 71/18.

Art as Therapy

EXHIBITION OVERVIEW

In a spirit of experimentation, the Gallery has embarked on a collaborative project with British philosopher Alain de Botton and philosopher and art theorist John Armstrong to bring to life their recent publication, Art as Therapy. In this already bestselling book, the authors pose questions that lie at the heart of art museums and their future well-being: How can art address issues that engage us all? How can art help us to understand ourselves and to lead richer lives? De Botton and Armstrong will select works of art from the AGO's diverse collection based on themes of universal significance, such as love, politics and money. Each theme will be installed in a separate space within the Gallery. Visitors can embark on a journey of discovery that will find them exploring different art, and a different part of themselves, in each space, or station. “Art,” according to the authors, “has a powerfully therapeutic effect. It can variously help to inspire, console, redeem, guide, comfort, expand and reawaken us.” Don't miss this innovative installation. It offers a unique opportunity to view both the AGO's collection — and ourselves — in an intriguing new way.

Click here to watch a recording of Alain de Botton's and John Armstrong's talk at the AGO on April 30, 2014.

Organized by the Art Gallery of Ontario

Art as Therapy: Sex

Problem: Thinking sex is just good clean fun.

On closer inspection this is quite a disturbing, even creepy, image. An average, slightly upmarket couple is kissing. To their friends they are respectable, quite successful. He has a good position as an officer in the military. She’s a bit of a society figure. They are a bit greedy, on the lookout for a bit of fun. Maybe they tell a few lies here and there to smooth things over. They are pretty imperfect, but they are not at all unusual.

But then, behind them and around them are the bizarre and confronting symbols and semi-divinities of the ancient world. As many works of art do, this one is telling us something about the minds of the central characters. These people carry within them a whole lot of strange baggage. They think of themselves as up to date. They have opinions and attitudes that, in their own circle, pass for enlightened. But the artist is telling us that deep down these people have, like everyone, destructive urges, obscure lusts, wild fantasies (which could sound deranged if described). They are haunted by the fear of death. The Egyptians gave names and faces to their dark parts of the mind. More often than not, we keep them hidden from view. But they are there all the same.

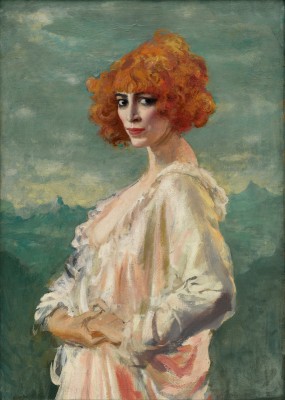

Problem: No one has ever asked me what I really, really want.

Is she terrifying, exciting or perhaps both? She’s looking at us, her viewers, with a particular kind of stare. She knows about sex, she wants it as much as we do, and nothing we might want is alien to her.

This is at once a great relief and deeply unusual. We spend most of our lives suppressing our libido in one way or another, and feeling shame and embarrassment about some of our fantasies. We don’t encounter too many Marchesas. Despite all the so-called “liberation,” sex typically remains underground and hidden. The Marchesa is on hand to give us the confidence and skill to overcome any doubts and embarrassments. We don’t yet know how to honour her achievements. She is a Professor of Desire.

Art as Therapy: Politics

Problem: It feels like a dog-eat-dog world out there.

Here is a picture about friendship and kindness. The men are going to be doing something important and difficult in the next few days, but right now they are just enjoying one another’s company, experiencing themselves as a close-knit team united by their desire to change the course of history. They all know each other well, but the conversation has broken up into small groups. They are spread out across the room, but they are all in this together. The white-haired man in blue is listening carefully while his younger companion adjusts a boot and talks of his plans. They are a band of brothers, drawn together by a common purpose and devotion.

Who is the leader in this group? It’s not clear at first, but of course there is Jesus — the man on the right with the apron, washing the feet of one of his friends. He’s being subservient, looking after the needs of his disciples, making sure they feel comfortable. Yet, as we know, in the Christian faith he’s the King of Kings. It’s moving that Christ should demonstrate his gratitude without any sense of his own importance — his true greatness emerges from his modesty.

We might, in a way, wish that some of this could happen to us, that we could be part of something immensely meaningful, a society of friends united by a lofty purpose. We like doing things in groups. But it’s rare for group life to go well. We are not good at teaming up. Maybe that’s because we don’t usually have a big enough or clear enough purpose.

Problem: I’m fed up with politics.

When we hear the word “politics,” our first reaction might be to think of the economy, parties angling for power, elections, the person who holds the top job, international relations. It’s not too surprising if we get disenchanted with this sort of politics at times. There is so much aggression, conflict, scheming, evasion and duplicity. But there is a wider idea of politics in the wings. It’s the maddeningly difficult, but noble, project of collective flourishing.

Helga is not so much the portrait of one particular woman as a representative of anyone, any stranger, any person you don’t know. Richter has depicted her slightly out of focus, so we have to strain to try to make out her features. He makes us feel that we don’t know her. He reminds us of something crucial which we normally forget: the mystery of other people.

For all its faults, democratic politics is the brave, hugely important attempt of people who don’t know each other well to try to live in peace together. There are terrible frustrations along the way because people are moved by such different things and have such varied needs and interests. And yet, in a few countries — Canada being conspicuous among them — most people do manage to live with reasonable civility alongside their neighbours. It’s deeply imperfect. But in our eagerness for improvements, we risk forgetting what an astonishing achievement this really is. We should be more grateful.

Problem: I tend to switch off when the news is too awful.

One big function of art is to show us suffering and injustice to which we have closed our eyes — and thereby encourage us to pave the way to a better world. Art takes the first crucial step of raising consciousness, and thereby helps to generate the political will to remedy big social ills. Vincent Van Gogh directed the attention of a prestigious urban audience to the plight of a hitherto neglected constituency: the rural poor.

Of course, it’s not that before van Gogh people in France weren’t aware of the horrifying statistics. The news — then and now — is always informing us of appalling facts. The average life expectancy for a peasant in France in 1880 was 35. One out of eight peasant women died in childbirth. To switch centuries, nowadays the unemployment rate in Greece is 28 per cent. The average wage in Liberia is less than $200 per year. And no one much cares....

That’s why we need art. The prestige of data is fed by the tempting but false idea that “knowing the facts” is what matters. Abstract statistics look clever and serious, but so often they just wash over us. The woman with a spade takes us in the opposite direction. We are creatures designed for intimate contact, for local lives and personal relationships. For ideas to become powerful in our souls, they need to be anchored in experience. We need to feel them, see them. This is what art, at its best, can help us with.

Problem: Thinking that criticizing the world is the best way to change it.

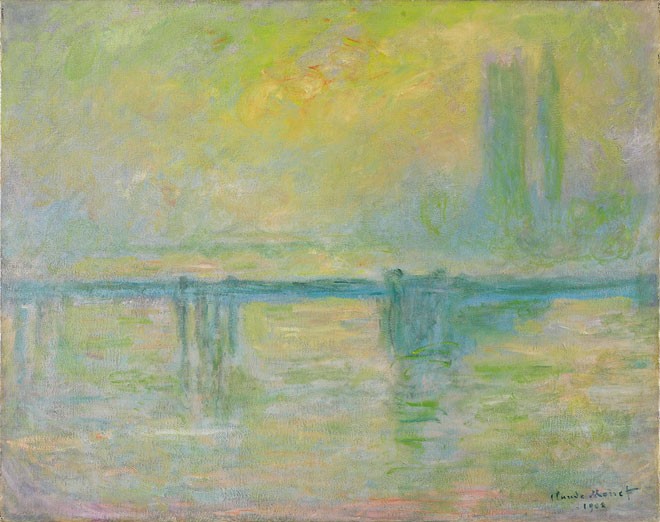

We might initially feel that Monet has painted an entirely apolitical picture. What could be more serene and ethereal than this vista? But the story behind the picture tells us something important about social change, which is, after all, one of the major ambitions of political activity.

Monet’s work was at first scathingly rejected. His paintings were regarded with intense suspicion. But it was not too long before they were accepted and acclaimed. Indeed by the time this work was painted, Monet had long been a very successful artist. Impressionism came to look obvious – exactly what you would expect a painting to be. So this work gives hope around progress. And it is helpful to consider how this happened.

Monet was not launching a fierce critique of the world; he was not trying to get people to see the errors of their ways or the injustice of existing institutions. That’s revealing, because we often suppose that social change comes about by pointing out — with great insistence — just how bad some existing thing is. Monet doesn’t do that. He does not show us what he hates. He shows us what he loves, and tries to get us to share his delight.

He delighted in the effect of fog upon a river and taught others to enjoy this as well. True progress need not originate in anger and criticism. Monet reminds us of something we easily forget: love and delight are central to improving the world.

Art as Therapy: Nature

Problem: I get cynical when things seem too nice.

Lorrain sought out particular moods that nature could speak to — and sought to intensify them in his pictures. He’s not trying to be realistic — perhaps no part of nature could be as artfully composed as this. Everything is calculated to make us feel wistful. It is evening, and the mild sunlight tinges the western sky. The shadows are lengthening, but far away on the horizon there is a distant island. The headlands break sweetly into the bay as the lines of the hills melt away.

Obviously, this painting is not paying much attention to the darker aspects of existence. That’s not because it is ignorant of them or wants to pretend that everything is rosy. Rather it is giving us a restorative break. It is deliberately drawing our attention to more delicate and sweet states of mind, because it understands how easily they get swamped by the tribulations of everyday life.

Art as Therapy: Money

Problem: It’s not enough to have money; it also has to be used well.

They are comfortably off — there’s enough money for a lavish dinner, an elegantly furnished room, fashionable clothes. But Rowlandson has chosen a moment when they are being very far from refined. They seem brutish, greedy, vulgar. For all their cash, they behave no better than anyone else.

Such a scene brings money into disrepute. All this had to be paid for. Somewhere out of sight, land was drained, cultivated, people laboured in the fields. It all happened so that some people could make enough money and be freed from immediate care. But all they do with it is amuse themselves in ridiculous ways. They don’t deserve to be well off. They should aim higher. Our disgust is a sign of our ambition for them.

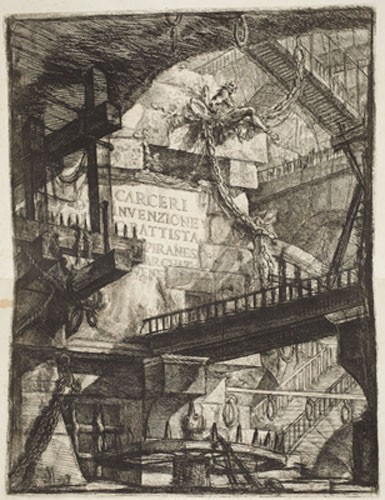

Problem: I’m trapped in money worries.

Our culture is so deeply impressed by money and values competence around money very highly, so it can feel very awkward to admit how frequently we feel frightened and bewildered in our financial lives. It’s not something you are supposed to feel. Yet often we do.

Piranesi’s imaginary prison might sometimes feel like a portrait of the inside of our heads when we worry about money. Every route turns out to be a dead end. You go off in one direction, only to find yourself back where you started. It’s impossible to break out.

There’s a key distinction between money troubles and money worries. Troubles are real: you absolutely have to pay for something. But often enough the anxieties around money are the work of imagination: we fear humiliation (rather than actual bankruptcy); we are worried about not getting some alluring luxury; it can feel imperative to earn more than a sibling, have a bigger house than a rival, stroll into business class rather than huddle with everyone else in economy. These worries can be very distressing. But in an important way they create an imaginary prison. They make us feel poorer than we really are. The solution might not be extra work to make more money. It might be greater self-knowledge.

Art as Therapy: Love

Problem: Saying I’m OK when I’m not really.

This picture shows us The Lady of Shalott, the heroine of a poem by the most successful British poet of the 19th century, Alfred Lord Tennyson. The story is set in the Middle Ages. The Lady spends her days living alone and isolated in her castle. The world goes by outside, but she stays indoors. She doesn’t participate. She doesn’t join in. She lives “in the shadows.” We might not actually live in a lonely castle, but the idea is powerful, because it stands for a feeling of missing out that haunts so many lives.

She has been on her own too long. She has plenty to do, but she still feels unfulfilled. Today she might be cooped up in the finance department. Outside her window, life is going on. Other people are setting out on adventures, falling in love, making this happen, making a difference. Yet she is afraid. What will happen if she goes out into the sunshine, if she breaks her isolation? To others these might seem like easy things. But not to her.

Frustration and disappointment are embarrassing. We are supposed to be successful. And sometimes the sheer pain of admitting distress can lead us into denial: “I’m fine, honestly.” Pain and psychological suffering may be inescapable parts of life, but works such as this one treat our sorrows with dignity. They try to lessen the personal sting by showing how others have been in similar situations, and they add a layer of sympathy. The Lady of Shalott is not an idiot or a fool. She is simply unlucky in her situation. Disappointment is normal. Self-knowledge is valuable even when it hurts.

Problem: Difficulty remembering why we ever got together.

They are so in love and it’s easy to see why. They are having such a good time with each other: teasing and gazing fondly into each other’s eyes. It seems a bit too good to be true, if we imagine it as telling us the whole truth about relationships. Of course, the troubles come along. There are worries about career, disagreements about how to furnish an apartment, fury at what might look to other people like tiny things. One day she will turn coldly on him for not cleaning his clogs before coming indoors; in time, he will get irked by how much she spends at the fruit shop.

But that’s not the point. This picture is a reminder of how most relationships start — two people in love with each other. Later on, when they are a bit sick of their relationship, they should look back on this image and refresh their sense of why, after all, they do love each other. The love has not disappeared — it has only been hidden by the normal distractions and frustrations of life.

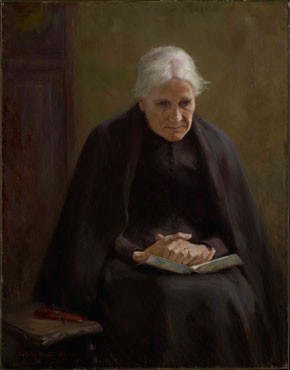

Problem: Thinking my ideal age range is 25–32.

This woman used to be strong and decisive; she had lovers once; she put her makeup on carefully and set out with a quiet thrill in the evening. Now she’s hard to love and maybe she knows this. She gets irritated, and she withdraws. But she needs other people to care for her.

Anyone can end up here, and there are moments when a lot of people — at whatever stage of life — are a bit hard to admire or like. Love is often linked to admiration: we love because we find another person so exciting and attractive. But there’s another aspect to love in which we are moved precisely by the needs of the other, through generosity. Tully is generous to her. The artist looks with great care into this woman’s face and wonders about who she really is.