Contemporary art goes outdoors

Artists Diane Borsato and Amish Morrell take us outside and into the pages of their new book, Outdoor School.

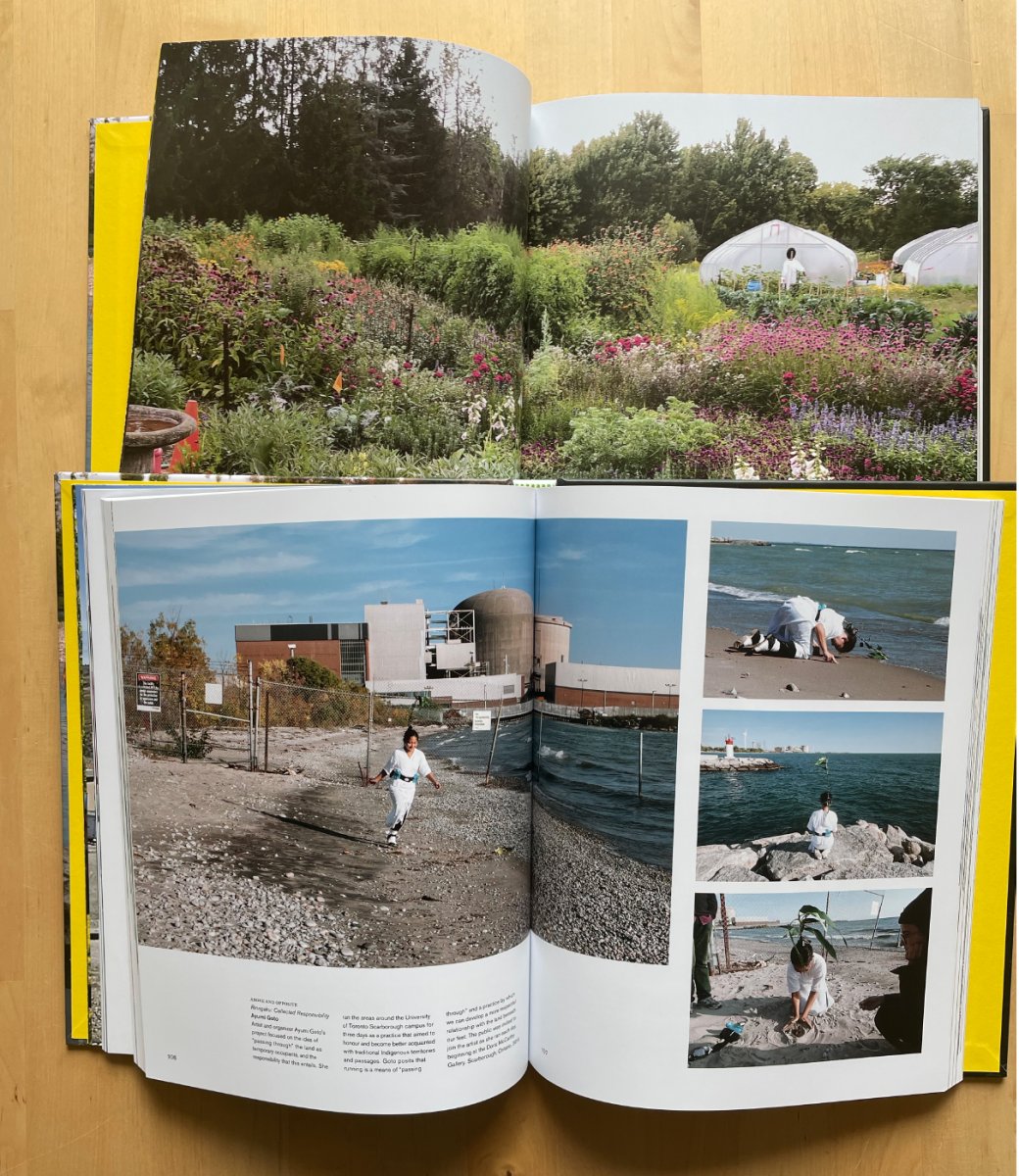

Image from Outdoor School, published by Douglas and McIntyre, courtesy of Diane Borsato and Amish Morrell.

Mushroom foraging, water witching and honey extracting are but a few of the outdoor activities that, according to Toronto artists Diane Borsato and Amish Morrell, can help us shift our views of nature away from scientific, commercial and colonial perceptions of land. Featuring over 150 photographs, interviews and essays (including one by Georgiana Uhlyarik, AGO Curator, Canadian Art), their new book Outdoor School is a primer for a new generation of ecologically inspired art, showcasing a variety of recent experiential and community-based projects.

We reached out to Borsato and Morrell to hear more about their inspiration for the project, and the intersections they see between the outdoors and contemporary art education.

AGOinsider: When and where did the idea for Outdoor School begin?

Morrell: It came about after a mushroom foray we led in August 2009, in Cape Breton. We invited some key members of the Toronto Mycological Society and advertised it in the local newspaper so that it brought together people who lived there, and who had rich knowledge of the forest and the land where we forayed and amateur experts with incredible specialized knowledge. It also attracted lots of artists! We were compelled by this idea of bringing people together in the outdoors, with different kinds of knowledge; cultural, scientific, culinary, aesthetic, in a convivial way where we learned from one another.

Borsato: To explore these things further, I later taught an advanced studio art course at the University of Guelph, called “Outdoor School”, where I had art students work with researchers, farmers, conservationists and naturalists to research and produce environmental art. And then, Amish organized an exhibition at the Doris McCarthy Gallery where artists made works that involved students engaging with the landscapes and ecologies around the University of Toronto Scarborough. All of these projects grounded art practice in collaborative ways of learning about where we are, and what is in our wider environment.

AGOinsider: How did you go about collecting and selecting works to include? What qualities did you look for?

Borsato: Most of the artists in the Outdoor School book were in the original exhibition at the Doris McCarthy Gallery, or were present during an Outdoor School residency we led at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity in 2018 with artist Tania Willard, whose now-famous The BUSH Manifesto is printed in the book. We were looking for projects that reimagine our relationship to the outdoors, to nature and the land, that are rooted in performance and site specificity. And also to teaching and learning.

AGOinsider: Due to the pandemic, nature has never been so popular. How do you think social distancing will impact how we see nature in the future?

Morrell: The outdoors has been a solace for many of us as we struggle with restricted mobility and limited contact with others. It’s also one of the places where we can safely be with others. We need to be wary of seeing nature simply as a site for recreation, as a resource, or as private property – something that we own or take from, or which is the backdrop to our daily activities. With more people spending time in urban parks and ravines, surrounding green spaces and provincial parks, it is important to recognize these as shared spaces. The coming together of people outside is a way to develop ecological literacy, have relationships with non-human creatures, create community and engage with different knowledge systems. This entails responsibilities to the soil, the water, the plants, animals and to people who occupy these places. Like all of Toronto, these are traditional territories for many Indigenous people. And they are places of rich sources of knowledge that we activate and practice by spending time outside. Artists in Outdoor School propose that we can learn together, with curiosity, humility, playfulness and generosity.

AGOinsider: Outdoor School explores a lot of alternative nature practices like mushroom foraging and water witching. Which of them were new to you? What was the most satisfying experiment?

Borsato: Amish is always in motion, he loves to hike up mountains, forge new trails, run through urban ravines as part of his creative practice. My interests are a little more still – I like to identify mushrooms and clouds, taste apples, read field guides and talk to naturalists. We loved working with artists who could expand our ways of being outdoors, like Alana Bartol’s water witching, or Hannah Jickling travelling by giant pumpkin boat, or Jay White’s practice of disappearing in the woods to be like a coyote, or Sameer Farooq, who has invented a method to know a landscape through a process he calls “somatic visioning”.

AGOinsider: What's a common misconception of land art that you wish to dispel?

Morrell: There is a history of land art that has regarded nature as raw material, or as a picturesque backdrop for an idea. Sometimes the land was carved, exploited and dumped on, without respect for an existing place and its inhabitants.

Borsato: The artists in Outdoor School work across the art/life divide to involve participants in ways that are embodied and relational. The artists in this book engage with the outdoors not just as a source of images or as raw materials, but to explore experiences and relationships. All of these artists pose alternatives to commercial, exploitative, competitive or neo-colonial ways of being outdoors. Theypropose new, critical and imaginative ways of being outdoors together.

AGOinsider: What distinguishes the ideas you’ve captured in your book, from previous back-to-the-land movements?

Morrell: There’s a big difference. Previous back-to-the-land movements were largely grounded in ideas of self-reliance and independence, and often leaving the city. The artist projects in Outdoor School emphasize inter-dependence and relationship, going back-to-the-land where you are, whether that is making works on a campus organic farm as the art students do, reclaiming traditional hunting knowledge as Tania Willards does, creating an orchard as a public artwork in a suburb as Diane has done, or developing new rituals that are grounded in a place, as Jamie Ross and Ayumi Goto do.

AGOinsider: Will Outdoor School reconvene this summer?

Borsato: Well, while we aren’t teaching in-person, or leading residencies or curating art exhibitions right now, many of the outdoor practices we explore are deeply entwined with living our lives. We are always doing some kind of research – through movement, study, and building relationships. It’s a time for practice, rather than a big production. We can’t wait to be near others again though – and as soon as it’s safe and allowable, we will be launching Outdoor School by inviting everyone to join us for a refreshing jump in Lake Ontario. Amish and I are hopeful this is coming soon. We can hardly wait.

As we look forward to opening the doors of the AGO again, we encourage everyone to spend more time outdoors in the shared space between us and nature. Want more news on inspiring art projects, virtual events and teasers for upcoming exhibitions? Sign up as an AGOinsider to get a batch every week to your inbox