On protest and place

Renowned artist Martha Rosler talks about politics, fake news and the importance of showing up.

Martha Rosler. Image by Tina Barney

Internationally acclaimed artist, educator and writer Martha Rosler believes there’s always more to what meets the eye. From a feminist perspective, her work focuses on revealing the politics and assumptions

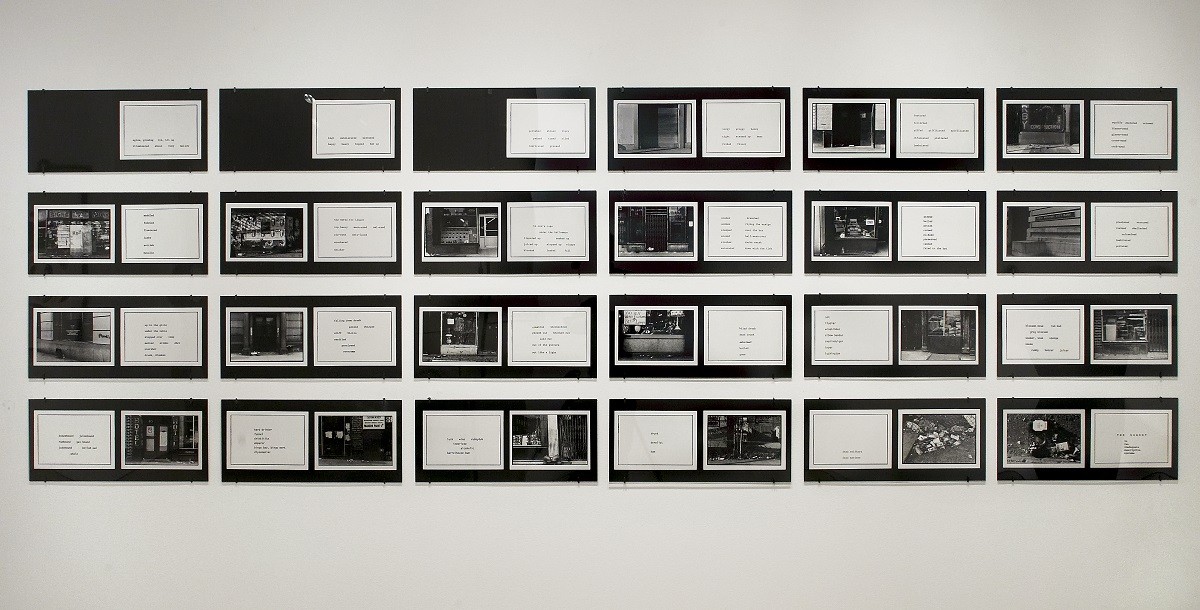

that inform our everyday lives. Her iconic photo-text piece, The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems (1974–75), is part of Documents, 1960s-1970s, and reminds us that a photograph isn’t simply a transparent window on the world, but rather reflects the social and cultural values of a specific time and place.

Contrasting images of lower Manhattan storefronts, devoid of people, with adjectives and nouns describing drunkenness, Rosler urges us to reconsider the authority we invest in images. Searching for answers, we asked Rosler to chat about this work and her artful activism.

AGOinsider: The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems (1974–75) was an intentional, incomplete portrait of a place. Have you been tempted to revisit this specific site? Has any media evolved since that time that might provide an accurate description?

Rosler: I’d stop a moment before accepting that the work is a portrait of a place. It’s a portrait of a quintessential kind of place—Skid Row—which lends it a semi-mythic, symbolic status, which is why photographers kept going there to capture images at a certain stage in the mid-20th century. The work was intended as an interrogation—if I may—of the forms of utterances that constitute or inhabit photographic documentary. It was not as an investigation of the Bowery in New York or its dastardly denizens (who are of course nowhere to be seen, and only collectively to be heard, in the systematically chosen, idiosyncratically organized texts).

A few years ago, Eungie Joo, the Curator of Education at the New Museum in New York, as it was about to open its high-profile building— on the Bowery— as a marker and goad for gentrification, invited me to participate in the show they were doing on the Bowery and its history. I faced a quandary: The Bowery was not a work about a place but about a way of seeing, of picturing— whereas Joo was, in fact, asking me to address the Bowery precisely as A place, THIS place, with its own particular local and geopolitical significance. I decided to try it. I made a work called Bowery Highlights (2008), a two-screen movie in photos about the gentrification of the Bowery. Some of the images showed new buildings, but many others showed the gentrification of the old low-rise tenements and industrial buildings from before the turn of the 20th century, many of them made recognizable in their new, upscale state by the addition of modular-design stories—generally four—on top of the old building. These pictures of buildings flowed by on one screen. On the other screen were documents of sale and habitation, Certificates of Occupancy, from the city’s Department of Buildings. And the title, Highlights, referred not only to the idea of prominent selection but also to the changed heights of gentrified buildings, and to the array of lamp and lighting stores for which the Bowery had long been famous and which figured in my work of 1974/75.

At this point, we have learned to understand the “meaning” of evolving city spaces as stories about financial/real estate boom and bust, and to regard what formerly was taken as explorations of local colour or the privileged testimony of local denizens, as sentimentalism, illicit voyeurism, or just plain genre entertainment instead.

As to the question of the evolution of media, the problem’s not with media but with meaning. Language itself is fundamentally ambiguous (thus the felt need for emojis on social media and texts to direct people’s readings), and although people love to claim that images don’t lie, we have to be schooled in reading them, even if only culturally, and they are laden with connotative meanings. We are often fooled by images. Moving images do a fuller job, perhaps, of filling in the meanings of “dumb images.” But advance? If anything, we’ve retreated in our sophistication, though—perhaps because we rely so heavily upon images, both still and moving.

AGOinsider: Long before “fake news” was even a term, your work was reminding us to look beyond a photograph, a film, or a text. In these uncertain times, where do you go for news?

Rosler: The idea of “fake news” is now firmly fixed in everyone’s mind, but really, we’ve been aware for a long time of the political and cultural uses of misinformation and even disinformation—the manipulative political use of lies and deceptions, generally by state entities. (I even made a work about it—a video and an installation, called If It’s Too Bad To Be True, It Could Be DISINFORMATION [1985]). The general aim is to destabilize target populations, something I think we’ve seen plenty of over the past few years, especially in the United States.

I’ve always read a lot of different publications, small lefty press materials, from populist to theoretical, and some mainstream ones too, and a couple of major newspapers—like The New York Times and occasionally The Globe and Mail, and The Washington Post— and more recently, an array of homemade political newsletters; the landscape keeps changing. I also read The London Review of Books. I check Twitter, and I follow Facebook because social media are the tribune of the era, but I never pay attention to TV news or opinion. And YouTube personalities—forget about it! But you have to be prepared to read most sources against the grain.

AGOinsider: You're well known for your participation in grassroots political causes like Occupy Wall Street. In the wake of the recent events in Washington D.C., has your faith in old fashioned protest waned or grown stronger?

Rosler: I was an antiwar and feminist activist decades before Occupy, of course. As someone schooled in the history of popular movements, I’d say the first precept is that a movement requires “feet on the streets.” Showing up, in public, is pretty much the only message from below that makes those in power take real notice. But when you are positioning yourself against power, it can’t be just a sometime, and certainly not a one-time, thing. Unless you are storming the Bastille, which in any case was part of a long series of organized actions.

AGOinsider: In 2013, you published an influential collection of essays entitled Culture Class, examining the role of artists in cities and gentrification. What role do artists have to play in the pandemic recovery?

Rosler: You aren’t alone in asking me about the arts in a pandemic, but as ever, I see the role of artists as to process, analyze, and join, or refrain from joining, trends in behaviour and analysis that have a collective bent. Artists, from early on in the pandemic, made online offerings and stood on balconies and sang, or straight up danced in the streets, but much of that activity was dedicated to the rescue of our much-challenged institutions: galleries and museums and other, more local art spaces.

Art can catalyze but it does not, to my mind, dramatically drive change. Only cheering it on, encouraging and accelerating it in certain circumstances. Certainly, artists may harbour messianic dreams, but we’ve done better joining our fellow citizens and residents in acting in public. Even in a pandemic … as long as we stay far enough apart and wear our masks. Which we did, during our virtually spontaneous, persistent, and widespread Black Lives Matter protests this past spring.

Want to know more about Rosler’s five decades-long practice and her work in Documents, 1960s-1970s? Check out her Art in the Spotlight talk below with Sophie Hackett, AGO Curator, Photography.

Talks and Performances supported by

Talks and Performances supported by

Lead Sponsor

Lead Sponsor