Questions and answers

How can we admire European art while acknowledging the colonial systems that produced it? European Art on First Nations Land, a new ongoing exhibition at the AGO, investigates this with select European and Indigenous works from the Collection.

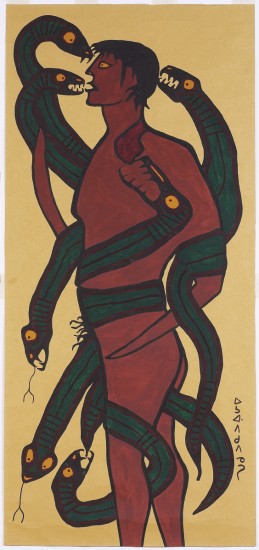

Installation view: European Art on First Nations Land, Ongoing. Artworks: Samuel Herbert Maw, Art Museum of Toronto: Sculpture Courts and Galleries, 1914.; Kent Monkman, The Academy, 2008. © Kent Monkman.; Norval Morrisseau, Self Portrait devoured by Demons, 1964. © Estate of Norval Morrisseau.; Gian Lorenzo Bernini, The Crucified Christ (Corpus), ca. 1650. Photo: AGO.

A thought-provoking exhibition is currently on view in the Reuben Wells Leonard Rotunda (gallery 115), one that draws visitors in with important questions about Indigenous and settler relations as well as the ramifications of colonization and slavery. What is our relationship between European art and the land we inhabit as Indigenous peoples and settlers? With six works from the AGO’s European and Indigenous Collections, as well as its archives, European Art on First Nations Land asks visitors to consider the role European Art plays in the history of colonization and the making of what is known as Canada. Even further, what role do art museums like the AGO have to play in this narrative? Paintings by Indigenous artists, namely Norval Morrisseau and Kent Monkman, are positioned alongside European sculpture and paintings from the 1600s and 1700s by the likes of Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Nicolas André Monsiaux. The juxtaposition is intentional. “One of the central questions I ask myself as a curator is if I can display European art in ways that do not continue to colonize the way we see,” explains Adam Harris Levine, AGO Assistant Curator, European Art, and the exhibition’s curator. “What happens when we understand that European paintings and sculptures are themselves settlers? Do we move through the European art galleries with new perspectives?”

Since 1911, the AGO has been housed on Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg territory (Mississauga) and the territory of the Wendat and Haudenosaunee. This land has been home to Indigenous peoples for thousands of years. History tells us that beginning as early as the 1400s, the wealth amassed by many European nations was built by forcibly using the labour of enslaved peoples and exploiting the resources of colonized lands. The profits from these enterprises financed art for the wealthy and powerful across Europe. When settlers travelled to the Americas, they imported their beauty standards, values and narratives. The AGO’s European Collection is robust and includes paintings, sculpture and other media from the Middle Ages to the Italian Renaissance and beyond. Featured in European Art on First Nations Land, Bernini’s bronze sculpture The Crucified Christ (Corpus) (ca. 1650) is a prime example. Like so many historical European masterpieces, the work is rooted in a system of oppression. Bernini’s artistic practice was funded by European nobility who spared no expense to decorate their palaces and chapels with religious paintings and sculptures. These families often funded their desires with profits from colonization and exploits around the world.

Internationally renowned interdisciplinary Cree artist Kent Monkman examines the complexities within the Indigenous experience, as it relates to themes of colonization, sexuality, loss and resilience. Through painting, video, performance and installation, Monkman challenges the European tradition in art history. The Academy, a 2008 Monkman painting commissioned by the AGO, is featured in European Art on First Nations Land as well. Monkman presents a critical take on the Gallery’s European Collection. His trickster response was to imagine a late-1700s European-style art academy within an imagined depiction of an Indigenous longhouse from the same time. He populates the scene with figures important to the history of art and the history of the Gallery. Also included in the exhibition and located on the opposite wall of The Academy is Zeuxis choisissant des modèles (1797) by French painter Nicolas-André Monsiaux. According to Greek legend, the artist Zeuxis was commissioned to produce a portrait of Helen of Troy, a character who represents idealized feminine beauty. His approach was to use five different women, highlighting the best features of each one. Monsiaux shows Zeuxis selecting his subjects from a group of naked white models. He also includes an enslaved Black woman, who kneels at the bottom right of the painting. Her presence places Black beauty beneath the white ideal in Monsiaux’s society. Monkman makes a direct reference to this in his Academy: Harriet Boulton, a founding figure in the AGO’s history, strikes the same pose as Zeuxis.

A highlight among the European works is a 1914 archival watercolour by Samuel Herbert Maw. It depicts proposed expansion plans for the sculpture and court galleries at the- then Art Museum of Toronto (now the AGO). At the time, this was the aspirational ideal for the Gallery—white visitors walking among sculptures from antiquity in an open courtyard, inspired by ancient Greek and Roman architecture. This watercolour painting brings into focus the AGO’s past as an institution. What can be said for the AGO’s future?

In addition to European Art on First Nations Land on Level 1, the AGO has a dynamic array of ongoing exhibitions currently on view. Experience Lisa Reihana: in Pursuit of Venus [Infected], Ragnar Kjartansson: Death is Elsewhere and Meditation and the Medieval Mind, along with all the other exhibitions, during your next visit to the Gallery. Read our Q&A about Meditation and the Medieval Mind with Adam Harris Levine on AGOinsider.