Chagall in his studio

Chagall and the Russian Avant-Garde: Masterpieces from the Collection of the Centre Pompidou, Paris

EXHIBITION OVERVIEW

The Art Gallery of Ontario is bringing the magic, whimsy and wonder of Marc Chagall to Toronto with a major exhibition organized by the Centre Pompidou. Chagall and the Russian Avant-Garde: Masterpieces from the Collection of the Centre Pompidou, Paris, features the lush, colourful, and dreamlike art of Marc Chagall alongside the visionaries of Russian modernism, including Wassily Kandinsky, Kasimir Malevich, Natalia Goncharova, Sonia Delaunay, and Vladimir Tatlin.

The exhibition examines how Chagall’s Russian heritage influenced and informed his artistic practice, illustrating how he at turns embraced and rejected broader movements in art history as he developed his widely beloved style.

Chagall and the Russian Avant-Garde comprises 118 works from a broad array of media, including painting, sculpture, works on paper, photography, and film. The artwork is drawn entirely from the collection of the Centre Pompidou and features 32 works by Chagall and eight works by Kandinsky.

Creating a New World: An intro to Chagall and the Russian Avant Garde

By: David Wistow, Interpretive Planner, AGO

Duration: 51:00

This talk is a personal look at the life of Marc Chagall and his art during a time of enormous social and political upheaval – World War I and the Russian Revolution of 1917. The talk offers a glimpse into Chagall's youth and Jewish upbringing, his search for a powerful new language of expression, his obsession with the village of his childhood and six decades of creative activity in exile. It also explores Chagall's friends and rivals – the Constructivists – who created radical forms of art to capture their vision of a new, idealized world of social equality.

A CLOSER LOOK

Chagall's “Double Portrait with Wine Glass”

“I had only to open my window, and blue air, love and flowers entered with her. She seemed to float over my canvases, guiding my art.” — Marc Chagall

In 1914 Chagall returned to his hometown of Vitebsk to marry his sweetheart, the beautiful, educated Bella Rosenfeld. This large painting commemorates their wedding day. Despite a backdrop of war and revolution, Chagall infused the work with unbounded joy, sensuality and optimism for a life together with his beloved.

Wedding portraits are common in the history of art. But never before had an artist chosen to depict the groom balancing on the shoulders of his bride. This unique solution/pose may refer to the Jewish wedding rite when the couple is carried and thrown into the air by their guests. Or does it more explicitly represent the key role that Bella played in her husband’s life as both muse and support?

“Only you – you are with me,” Chagall wrote in his memoirs. “When I gaze earnestly at you, it seems to me that you are my work… Guide my hand. Take the paintbrush and, like the leader of an orchestra, carry me off to far and unknown regions.”

Bella floats over Vitebsk and the Dvina River which bisects it. Chagall smiles and raises his glass to toast their new life, happily married and freed by the Revolution from czarist restrictions placed upon all Jewish people. Above them hovers an angel, a reference to their baby daughter Ida.

Bella brought enormous security and tranquility into Chagall’s life. When she died in 1944, he was devastated. His vital link to Jewish Russia was gone.

“I have lost,” he wrote, “the one who was everything to me – my eyes and my soul.”

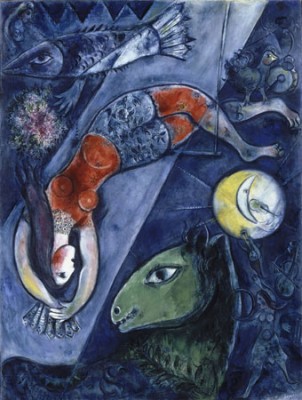

Chagall's “Blue Circus”

“For me, a circus is a magic show that appears and disappears like a world. A circus is disturbing. It is profound.”

“I can still see in Vitebsk, my hometown, in a poor street with only three or four spectators, a man

performing with a little boy and a little girl. Clowns, bareback riders and acrobats have made

themselves at home in my visions. Why? Why am I so touched by their makeup and their grimaces?

With them I can move toward new horizons. Lured by their colours and makeup, I dream of

painting new psychic distortions. Alas, in my lifetime I have seen a grotesque circus: a man [Hitler] roared to terrify the world.”

“A revolution that does not lead to its ideal is, perhaps, a circus too.”

“I wish I could hide all these troubling thoughts and feelings in the opulent tail of a circus horse

and run after it, like a clown, begging for mercy, begging to chase the sadness from the world.”

— Marc Chagall, 1966

THEMES

In the early 1900s, against a backdrop of social change, war and revolution, a generation of Russian artists sought to make a new kind of art that was powerful, authentic and modern. While some turned to peasant subjects and folk art for inspiration, Marc Chagall made paintings that evoked his Jewish roots, his family and his inner life.

This exhibition explores for the first time the relationship between Chagall and his Russian contemporaries, tracing their paths from Russia to France and Germany and back again. It highlights their shared sources of inspiration, the way they embraced new artistic directions before and during World War I, and how, fuelled by the Russian Revolution of 1917, many turned to art as an engine of radical social change. The exhibition also reveals how the artists forged unique contributions to modern art, as their paths diverged.

Russia: In Search of Roots

Prior to 1910, many young Russian artists sought a new and stronger language of expression. They were inspired by rural life and authentically Russian traditions, such as icons, folk art, wood prints, store signs, toys and embroideries, with their bold patterns, colours and forms. These artists eagerly absorbed the ideas in the avant-garde paintings of Western European artists like Paul Gauguin (then on view in Moscow and St. Petersburg), finding a similar vibrancy and expressive power in their work. Goncharova and Larionov developed these ideas in Moscow, while Kandinsky and Jawlensky brought these discoveries to Munich.

Artistic Advances in Paris and Russia, 1911–1914

“The sun of art shone only in Paris,” Chagall once said. He moved there in 1911, settling in La Ruche (French for “the beehive”), a complex of more than 100 studios. There he lived alongside many immigrant Russian artists including Archipenko, Zadkine and Lipchitz, whose works are also featured in this gallery. Chagall immediately sought out the work of Paris’s most radical French painters such as Paul Cezanne and Henri Matisse. Full of excitement, Chagall solidified a new artistic language of vivid colour, distorted space and geometric forms. Yet his paintings remained rooted in the human figure and his beloved Vitebsk. His approach differed from the more radical experimentation of his Russian contemporaries (back home and in Paris), whose works became increasingly abstract.

Return to Russia

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 prompted many Russian artists to return home from abroad. “Vitebsk – I came back to it with emotion. I painted everything I saw,” Chagall wrote. Despite the war, these were perhaps the happiest and most productive years of his career. Newly married and soon to be a father, he revelled in his young family, the rituals of his Jewish community and, following the Revolution in 1917, new freedom and hope.

Vasily Kandinsky, also returned to Russia from Europe with his wife. The couple settled on a cousin’s idyllic country estate near Moscow, which offered a wealth of pastoral subjects. His homecoming rekindled his focus on Russian scenery and landscape while he continued to explore abstract painting.

Art and Revolution

“Build a new world!” cried the young artists. Liberated by Russia’s Revolution of 1917, they began to transform a dream of social equality into reality. For those dedicated to the Constructivist movement, art was no longer a bourgeois luxury but rather a political tool meant for the street, the factory, the worker and the masses.

The Soviet state harnessed the energies of painters, sculptors, photographers and architects to carry its message of equality and freedom to its citizens. The Constructivists no longer found themselves at the periphery of society. In 1918 Chagall became Arts Commissar for the province of Vitebsk and founded the Vitebsk People’s Art College, but soon his personal subjects seemed out of step with the radical new world of politics, industry and geometric abstraction.

Chagall's World of the Theatre and the Circus

“It is a magic word, circus, a timeless dancing game of tears and smiles.” Since childhood, Chagall had been fascinated by the circus and theatre. Jewish theatre production had been forbidden before the 1917 revolution. In the early 1920s, however, with the founding of Moscow’s Jewish Chamber Theatre, Chagall designed costumes, sets and murals that expressed Russia’s new social, political and religious freedoms. In subsequent decades he returned repeatedly to the theme of the circus for inspiration. “For me, a circus is a magic show, disturbing, profound. I have always looked upon clowns, acrobats and actors as beings with a tragic humanity.” Yet Chagall’s circus animals and figures seem to mirror life’s sorrows and its joys, as they float in a fantastical world of colours that glow like stained glass.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

From the drab surroundings of the Jewish quarter (or “shtetl”) in the city of Vitebsk in Belarus, Marc Chagall created a highly personal style of modern art. Yet his themes of love, loss, joy, memory and family are universal. Chagall combined real and dream worlds into richly coloured fantasies where people fly and animals cavort. Over a long life spent mostly in exile in France, Chagall continually expressed deep longing for the Russia and Vitebsk of his childhood. Until his death at age 97, he sustained an almost mystical union with this special place and time.

1887: born in Vitebsk, Russia (now Belarus), the eldest of nine children. His father was a fishmonger

1890s: attends a traditional Jewish school before entering the local Russian high school at age 11

1907: arrives in St. Petersburg illegally, as Jews were forbidden to reside there without a permit – spends three years studying painting, and encounters modern French art

1911: settles in Paris at a studio complex called La Ruche (French for “the beehive”) along with fellow Russians Archipenko, Zadkine and Lipchitz. Absorbs the latest developments in French art

1912: exhibits at the Paris Salon d’Automne and Salon des Independants (again in 1914)

1913–1914: exhibits work in Berlin that helps launch his international reputation

1914: returns to Vitebsk

1915: marries Bella Rosenfeld who gives birth to their daughter Ida – begins a series of fifty paintings documenting life in Vitebsk, including the famous Double Portrait with Wine Glass on view in this exhibition – sells thirty works to one Jewish collector for a future Jewish art museum

1917–1918: Russian Revolution breaks out. Jews are granted full status as Russian citizens – appointed Commissar for the Arts in Vitebsk – founds the Vitebsk Art School which he directs from

1919 to 1920. Invites fellow Russians Ivan Puni, El Lissitzky and Kazimir Malevich to teach there

1920: leaves for Moscow where he designs sets for the new Jewish Chamber Theatre

1922–1923: Chagall and his family immigrate to Paris

1941: seeks asylum in the United States during World War II

1944: His wife Bella dies in New York

1948: returns to France

1950s and 1960s: takes up new media such as stained glass, ceramics, sculpture and large-scale mural painting – concentrates on the themes of the circus and theatre

1985: dies at age 97

THE RUSSIAN AVANT-GARDE

Alexander Archipenko

(born Kiev, Ukraine, 1887; died New York City, United States, 1964)

The sculptor Archipenko studied in Kiev (1902–1905) before moving to Moscow. By 1909 he was living in Paris in the same studio complex as Marc Chagall. Archipenko was a dedicated teacher who opened art schools first in Berlin and, after World War II, in New York, Los Angeles and Chicago.

Vladimir Baranov-Rossiné

(born Kherson, Ukraine, 1888; died Auschwitz, Poland, 1944)

The painter Baranov-Rossiné studied art in Odessa (1903–1908). He participated both in Jewish and contemporary art exhibitions in several cities including Moscow, Kiev, St. Petersburg and Paris. In 1925 he immigrated to France. He was arrested by the Gestapo in 1943 and died in Auschwitz the following year.

Natalia Goncharova

(born Negaevo, Russia, 1881; died Paris, France, 1962)

Goncharova was a painter, stage designer, printmaker and illustrator who did much to revive Russian folk art. She began studying art in Moscow where she met painter Mikhail Larionov, whom she later married. Both were central figures in the Russian avant-garde art movement. They immigrated to France in 1919.

Alexei Jawlensky

(born Torzhok, Russia, 1864; died Wiesbaden, Germany, 1941)

After studying at a Moscow military academy, Jawlensky entered art school in St. Petersburg. He settled in Munich in 1896, but continued to exhibit in Russia. In 1906 his works were shown in Paris, where he met Henri Matisse. He spent several summers in Germany with Vasily Kandinsky. In 1921 Jawlensky settled permanently in Wiesbaden.

Vasily Kandinsky

(born Moscow, Russia, 1866; died Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, 1944)

Kandinsky was a central figure in the development of 20th-century abstract painting. After studying economics and law, he turned to painting and moved to Munich. The war forced him back home to Russia in 1914, but he would return to Germany in 1921. Kandinsky became a leading source of inspiration for younger generations of abstract artists during the mid-1900s.

Ivan Koudriachov

(born Kaluga, Russia, 1896; died Moscow, Russia, 1972)

Koudriachov studied art in Moscow from 1912 to 1917. Settling in the Ural Mountains in 1918, he returned to Moscow in 1921 where he became a set designer for the theatre and exhibited abstract paintings. Koudriachov survived the Stalinist period, and near the end of his life he created variations of his work from the 1920s.

Mikhail Larionov

(born Tiraspol, Moldova, 1881; died Fontenay-aux-Roses, France, 1964)

Painter and stage designer Mikhail Larionov was a leader of the Russian avant-garde before World War I, founding the movement known as Rayonism. In 1907 he began collecting icons and children’s art. He left Russia in 1915 with his wife, painter Natalia Goncharova. By 1919 they had settled in Paris where Larionov worked as a set designer.

Jacques Lipchitz

(born Druskininkai, Lithuania, 1891 died Capri, Italy, 1973)

Jacques Lipchitz studied commerce before travelling to Paris in 1909. There he attended art school and made regular visits to the Louvre. He became friends with fellow Russians Marc Chagall, Ossip Zadkine and Alexander Archipenko, and rented a studio at La Ruche, a renowned artist's residence in Montparnasse. Lipchitz continued to work in France until 1941, when he immigrated to the United States and gained recognition as one of the century's outstanding sculptors.

El Lissitzky

(born Pochinok, Russia, 1890; died Moscow, Russia, 1941)

Refused entry to the art academy in St. Petersburg because of his Jewish background, El Lissitzky instead studied in Germany and Moscow. He illustrated Yiddish books and organized exhibitions of Jewish art. In 1919 Marc Chagall invited him to teach in Vitebsk. As a graphic designer and painter of abstract works known as Prouns, El Lissitzky played a key role in the Constructivist movement.

Kazimir Malevich

(born Kiev, Ukraine, 1878; died Leningrad, Russia, 1935)

Malevich studied art in Kiev and Moscow. In 1919 he began teaching at the Vitebsk People’s Art College, which was directed by Marc Chagall. Malevich was a central figure in the Russian avant-garde movement. He pursued a pure geometric abstraction (with no reference to any recognizable form) known as Suprematism, which influenced much 20th-century art.

Pavel Mansouroff

(born St. Petersburg, Russia, 1896; died Nice, France, 1983)

Mansouroff began studying art in St. Petersburg in 1909. During World War I he trained in the air force, where he became interested in the aesthetics of airplanes. In 1918 he exhibited abstract paintings in the Winter Palace, former residence of the czars. Mansouroff’s radical art began to attract criticism from the State after 1925, and in 1929 he settled in Paris.

Antoine Pevsner

(born Klimovichi, Belarus, 1884; died Paris, France, 1962)

Painter and sculptor Antoine Pevsner was the son of an industrialist. He studied art in Kiev and St. Petersburg before he travelled to Munich and spent three years in Paris beginning in 1911. In 1917 he returned to Russia and soon began to make precise geometric abstract paintings. In 1923 he and his wife settled permanently in Paris.

Ivan Puni

(born Repino, Russia, 1892; died Paris, France, 1956)

Puni was a painter, illustrator and designer. In 1910 he studied in Paris, but returned to St. Petersburg by 1912 and became a key innovator in the avant-garde movement. His abstract three-dimensional paintings were shown together with the first Suprematist works in 1915. Four years later, at the invitation of Marc Chagall, he taught at the Vitebsk People’s Art College. He settled permanently in France in 1924.

Alexander Rodchenko

(born St. Petersburg, Russia, 1891; died Moscow, Russia, 1956)

Rodchenko’s work spanned painting, sculpture, design and photography. He became deeply involved in revolutionary politics and played a central role in the Russian Constructivist movement. In 1919 he became a master of photomontage (cutting and reassembling photographs), creating many emblematic revolutionary images. In the 1930s Rodchenko designed costumes and sets for theatre and film.

Vladimir Stenberg & Georgii Stenberg

(born and died Moscow, Russia, 1899–1982) & (born and died Moscow, Russia, 1900–1933)

The Stenberg brothers were sculptors as well as graphic and set designers who studied art in Moscow from 1912 to 1917. They worked together on decorations for the 1918 commemoration of the Russian Revolution, and organized an exhibition of Constructivist art in 1922. George’s accidental death in 1933 ended their collaboration.

Dziga Vertov

(born Białystok, Poland, 1896; died Moscow, Russia, 1954)

David Kaufman (pseudonym Dziga Vertov) was a pioneer of early documentary film. In 1920 he joined the October Revolution propaganda train to record its journey. After his bold approach was rejected by Russian officials, he turned to studios in Ukraine for support. His masterpiece is this experimental film Man with a Movie Camera.

Ossip Zadkine

(born Vitebsk, Biélorussie, 1890; died Paris, France, 1967)

The sculptor Zadkine was born in the same town as Marc Chagall. His father was Jewish (but converted to Russian orthodoxy) and his mother was of Scottish descent. After studying art in England, Zadkine settled in Paris in 1909, living in the same studio complex as Chagall. He never returned to Russia.

CHAGALL'S ESSAYS

These essays address the wide range of themes and stylistic approaches in Chagall's paintings, sculptures and drawings. Particular attention is paid to the development of the Russian avant-garde, from neo-primitism to Constructivism, on Chagall, its influence on Chagall, as well his status as a lone wolf among his Russian counterparts. The essays originally appeared in Chagall et l'avant-garde Russe, edited by Angela Lampe, and published by the Centre Pompidou. The complete French catalogue is available for purchase at shopAGO.

Chagall in Dialogue with the Russian Avant-Garde

Translated by: Wyley Powell

When Wassily Kandinsky turned 60 years old on December 4, 1926, he received the following letter from Marc Chagall:

“Dear Vassily Vassilievich, it is with joy and pleasure (emotions I rarely experience outside the homeland) that I send you my greetings, for you are one of a handful of Russians who have gained their artistic freedom and are taking advantage of it even from afar. At the present time, you are the only Russian artist who is thoroughly respected and loved. Live your life and pursue your work: you belong to that category of people for whom the age of sixty is really just three times twenty.

Cordial greetings to your wife.

Devotedly yours, M. Chagall”1

This seemingly banal congratulatory letter, part of the Kandinsky Archives that were bequeathed to the Centre Pompidou by the artist’s widow in 1981, is interesting on two accounts. In the first place, it reveals a personal bond between two artists who, in spite of a similar journey – they began their careers in Western Europe, returned to Russia, held positions in art education following the October Revolution, isolated themselves from the new movements and trends, and eventually emigrated – were never particularly close.

Their works nevertheless adorned the same gallery walls. In 1918, Herwarth Walden mounted a joint Chagall-Kandinsky exhibition, in the absence of the artists, at his Berlin gallery Der Sturm, supplementing it with sculptures by William Wauer.2 The following year, both artists were co-participants – along with Malevich, Exter, El Lissitzky, Rodchenko and others – in the First National Exhibition of Paintings by Local and Moscow Artists at the Borokhov Club in Vitebsk. In spite of these encounters, however, the two Russians kept their distance from each other. The explanation for Chagall’s sending this warm birthday letter may lie in the fact that he was a member of the Bauhaus Circle of Friends, a support committee established in 1924 in the wake of budget cuts imposed by the City of Weimar.3

There is also another reason why this letter is surprising. Within these few lines, Chagall twice links the master of Bauhaus, who was on the verge of becoming a German citizen, to his national roots in Russia. Such insistence would appear to rule out a perfunctory stock expression of congratulations for the occasion. What mattered for Chagall was the fact that the great Kandinsky was his compatriot, and the result was an ambiguous letter containing compliments that can be read as a bitter acknowledgement of his own situation as an émigré. The only way in which Chagall could construct and define himself was in terms of his origins, writing in 1936 with great clarity: “Although the world views me as an ‘international’ [artist] and the French consider me to be one of their own, I think of myself as a Russian artist and take pleasure in doing so.”4

A number of studies have examined the links that Chagall maintained with the arts and literature, and his reflections on the country of his birth. The first such study was Jean-Claude Marcadé’s initial analysis, published in 1984.5 This same author also focused more specifically on the relationship between Chagall and the Russian avant-garde.6 These comparisons did not, however, have any effect on how the exhibitions were conceived and, much like the major travelling exhibition of the mid-1990s titled Marc Chagall: The Russian Years, 1907–1922, they were limited exclusively to Chagall’s work.

It is true that a few of his paintings have occasionally been included in such collective events as the Maeght Foundation’s La Russie et les avant-gardes7 (Russia and the Avant-Gardes) in 2003, or the 2005 project in Brussels entitled Russian Avant-Garde: 1900–1935.”8 Nevertheless, this modest presence did not result in a revealing dialogue among the various protagonists. In general, the exhibitions devoted to Chagall have emphasized the singularity of his genius, which followed no rules other than those of its own poetic necessity.

However, it would be difficult to deny the fact that Chagall did fit into the context of contemporary creation – at least until his final departure from Russia in 1922. The child of Vitebsk was not an artist living in his isolation from his peers. His paintings kept company with the neo-primitive works of Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, who were proclaiming an authentic new Russian art as early as 1907. In Paris, his neighbours at the La Ruche studio were Ossip Zadkine, Alexander Archipenko and Jacques Lipchitz – Russian artists who, like Chagall, were seeking to assimilate the latest French trends. As director of the Vitebsk People’s Art College from 1919 to 1920, Chagall also came face to face with Ivan Puni, El Lissitzky and the Suprematist Kazimir Malevich, all proponents of a new non-objective type of art that was the polar opposite of Chagall’s figurative painting. With the advent of the Constructivist movement, which called for utilitarian art for the community, Chagall turned to stage art. These diverse areas of art were rich in contacts and encounters that left their mark on him in varying degrees – sometimes in a positive sense and sometimes with his back turned away from the current trends.

During an interview in 1973 with Russian historian Alexander Kamenski, Chagall himself stated: “It would be strange to have the works I painted in Russia exhibited next to those of European painters. Instead, they should find their place in museums dedicated to early 20th-century Russian art.”9 Thanks to the rich collections of the Musée National d’Art Moderne, we can now exhibit Chagall side by side with his compatriots and, for the first time, present this fertile dialogue that the painter had wished for. This groundbreaking project originated in the outstanding Chagall collection, which was acquired through the generosity of the artist and his heirs and came directly from his studio.

Among the first significant gifts made to the Musée National d’Art Moderne when it opened in 1947 was the magnificent Double Portrait with Wine Glass (1917–1918), which would later be enhanced by the famous Chagall by Chagall pieces. These works remained in the artist’s possession until his death in 1985 and became part of the collections three years later through a gift to the French State. Alongside nearly 500 drawings and gouaches are forty-five major paintings which include such major works as The Dead Man (1908), which Chagall’s biographer Franz Meyer characterizes as the “first summit” of his work; Studio (1910), which reveals the influence of Matisse and was probably one of the first paintings that Chagall completed after arriving in Paris in May 1911; and, most notably, The Wedding (1911–1912), a remarkable fusion between the poetic universe of the shtetl and the formal inventions that grew out of Cubism. Nor should we forget the second version of The Cattle Dealer (1922–1923), which Chagall painted to replace the 1912 version that he left behind in Berlin following his departure for Russia in 1914.

His theme – the world of the peasantry – reveals an affinity with the neo-primitive paintings of Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, which drew on popular “imagery” to create a new so-called “leftist” vernacular art. In 1995, the French public had an opportunity to discover the scope of the collections of these two artists housed at the Musée National d’Art Moderne.10 Following its first acquisitions of the 1930s and the post-war period, the museum built its collections primarily through a major donation from the Soviet Union in 1988 following the death of Larionov’s widow, Alexandra Tomilina-Larionov.

Today it includes nearly 340 works in various media by Goncharova and approximately 80 works by Larionov. A few of these, such as Goncharova’s Still Life with Lobster, Woodcutters and Harvest series, and Larionov’s Soldier’s Head, all of which were featured in the Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) exhibitions, came from Kandinsky’s personal collection and entered the museum through Nina Kandinsky’s exceptional bequest in 1981. Together with Malevich’s solemn Study of a Peasant, presented in 1912 in the second Blaue Reiter exhibition at the Hans Goltz Kunsthandlung in Munich, this collection provides an illustration of the close bonds and community of spirit that existed just prior to the Great War between the Russian avant-garde and Munich Expressionism.

Kandinsky’s Improvisation III, one of his major early paintings, was exhibited next to works by David Burliuk, Larionov and Goncharova at the Izdebski Salon in Odessa in 1910–1911. Their common sources of inspiration were the popular arts, notably the famous lubki – wood engravings sold in Russian markets – or small icons such as those which Kandinsky was fond of collecting and keeping in his studio. His archive included a good ten or more of these objects and folk prints.

Chagall maintained fairly close contact with this neo-primitive universe that came into being during his training years in St. Petersburg, as can be seen in his chromatic expressiveness, his terse stylistic effects and his reverse perspectives. However, he distanced himself from it as soon as the movement evolved in the direction of abstract art. Initially, a certain parallel was established as Cubism was being assimilated both by the Russian émigré artists in Paris and by the Cubo-Futurist painters in Russia. Besides Chagall, the first Paris School is quite well represented in the collections of the Musée National d’Art Moderne, notably by the works of sculptor Jacques Lipchitz – thanks to a generous donation from the Jacques and Yulla Lipchitz Foundation in 197611 – and by the representative sculpture ensembles of Ossip Zadkine and Alexander Archipenko. This juxtaposition of two methods employed by Russian artists to appropriate the Cubist idiom for themselves came to an end with Larionov’s invention of Rayonism in 1912. From that point on, Russian avant-garde art would merge with abstraction.

When Chagall returned to Russia in 1914, he arrived in a country where The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings: 0.10, the original manifestation of Suprematism, was mounted in Petrograd the following year. Kseniya Boguslavskaya, the widow of Ivan Puni (known in France as Jean Pougny), made a gift to the French State in 1966 of 53 of her husband’s works. Such generosity made it possible for the Musée National d’Art Moderne to present a group of works that appeared in the legendary exhibition organized by Puni and Boguslavskaya: the pictorial relief The White Ball, the illogical painting The Hairdresser and three abstract reliefs reflecting Tatlin’s research.

This ensemble was crowned by Malevich’s masterpiece (Black) Cross, which, as shown by the only existing photograph taken at the 0.10 exhibition, hung on the wall to the right of the first Black Square on a White Background, which was positioned like an icon in the upper right corner of the room. This historic painting became part of the collections in 1980 thanks to a gift from the Scaler Foundation and the Georges Pompidou Art and Culture Foundation.12

It is unlikely that Chagall attended the Petrograd exhibition. Following his arrival in Vitebsk, he married Bella Rosenfeld and began painting what he would call “documents” – some fifty or so canvases of people around him, of his conjugal life, family, neighbours and hometown, using an almost naturalist style.13 Moreover, these works represent a surprising parallel with a certain number of figurative pieces painted by Kandinsky, also after his return to Russia. It wasn’t until 1917, the year of the Revolution, that Chagall would be caught up in a new creative impulse, an impulse that can be seen in a series of major paintings – Double Portrait with Wine Glass, Cemetery Gates and the magnificent drawings Forward, Forward and Chaga. After becoming a free citizen, the Jewish artist entered politics and became the arts commissar for the Vitebsk region in August 1918.

In Moscow, Kandinsky was appointed to various revolutionary committees involved in art education and museum administration. During these heady times, though his pictorial production decreased, he created the masterpiece In the Grey, which he would later come to see as the end of the “dramatic period” that had begun in Munich.14

For his part, Chagall received authorization to establish the Vitebsk People’s Art College (it would change names a number of times15), which he opened on January 28, 1919. He fully subscribed to the idea that the avant-garde was a driving force in the new society and sought to bring all of the artistic trends together irrespective of their aesthetic qualities. Puni was asked to be in charge of graphic propaganda while his wife was responsible for the applied arts. But the couple left the school six months after it opened.

El Lissitzky, a close friend of Chagall’s for many years, arrived that summer and would direct the department of architecture and graphic art. It was he who extended an invitation to the charismatic Malevich, and as soon as Malevich arrived in November 1919 he stole the limelight from Chagall, transforming his school into the headquarters for Suprematism and UNOVIS (a movement of the champions and founders of what is new in art). Chagall’s figurative painting no longer seemed aligned with the demands of this new revolutionary era. Disillusioned, he left his hometown for Moscow.

There is a surprising painting in the collections of the Musée National d’Art Moderne, atypical of Chagall, which seems to be a commentary on this troubled period in Vitebsk – Cubist Landscape. By inserting his signature several times and in various languages, as well as a small figurative scene – a man (Chagall himself?) strolling with a green umbrella in front of the white building of the Vitebsk People’s Art College – he imbued this composition, characterized by fragmentation and marshmallow-toned surfaces, with an aspect of parody. There is even the suggestion of a settling of scores with the advocates of non-objectivity who, in December 1919, transformed the building of the Vitebsk Committee for the Struggle against Unemployment, known as the White Barracks, into an enormous Suprematist painting.

Chagall, with his impish and mischievous wit, played with abstract motifs from Cubism or Suprematism in his figurative narrations. He juggled with these codes in the way an acrobat would have done – and indeed the acrobat happened to be one of the themes he so enjoyed painting. This playful way of appropriating new trends for his own purposes became evident in his projects for the new National Jewish Chamber Theatre in Moscow. Between 1920 and 1922, Chagall designed a whole series of stage sets and costumes; many of these came into the collections of the Musée National d’Art Moderne through the 1988 donation.

It is probably because of his involvement with the theatre that connections can be established between Chagall and the collective ideals of the emerging new Constructivism even though his pictorial work was different, both esthetically and formally. The museum’s collections bring together a group of interesting works, in a variety of media, revolving around this movement. The multidisciplinary exhibition Paris-Moscow 1900–1930, with its groundbreaking presentation of 2,500 works and documents in 1979, was particularly beneficial in establishing this collection. Thanks to this exhibition, we have reconstructions of such emblematic works as the famous Model of the Monument to the Third International by Vladimir Tatlin and the Workers’ Club produced by Alexander Rodchenko for the 1925 Exhibition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Arts in Paris.

This exceptional event, which would be presented in Moscow in 1981 at the Pushkin Museum, was the result of a close collaboration with the Soviet partners. It also created a favourable climate for gift solicitation and laid the groundwork for subsequent acquisitions and bequests, thanks to the contacts established during the long years of preparation. In particular, this exhibition reinforced the ties with Alexandra Tomilina-Larionov and Nina Kandinsky, who would later agree to make a number of extraordinary bequests and donations.16 The Malevich collection also comes to mind, enriched in spectacular fashion in 1978 through an anonymous gift that included two late paintings and, of particular interest, 800 plaster elements, which enabled the reconstruction of five “Architectons.” The family of Alexander Rodchenko also donated a number of photographs to the Museum in 1981.

This collection of Russian avant-garde works has never been exhibited in its entirety – perhaps because of a genuine fear that it would not be possible to present it as a meaningful whole. Indeed there are gaps in the collection; for example, missing are works by Lyubov Popova, Olga Rozanova and the Burliuk Brothers, paintings by Alexandra Exter, Rodchenko, El Lissitzky, Tatlin and Ivan Klioune, as well as architectural models and films. The challenge we faced in this exhibition was to put forth a cross-cultural perspective of this collection while juxtaposing it with the works of Chagall at various significant times to show both the similarities and differences between him and his compatriots. With this groundbreaking dialogue, we hope to not only present Chagall’s works in a new light but also to reveal the high quality of this collection in all of its richness and variety.

- Handwritten letter from Marc Chagall to Wassily Kandinsky, November 15, 1926, Boulogne, Wassily Kandinsky Collection, Russian Correspondence, R 30, Kandinsky Library.

« Дорогой Василий Васильевич, Радостно, удовольствие (столь редкое вне первой родины) приветствовать мне Вас. Вас, редкого русского овладевшего свободой в искусстве и пользующагося ею даже вдали. Вы единственный русский художник которого сегодня уважаешь и любишь до конца. Живите и рaботайте : Вы из тех кому не 60 лет а три раза по 20. Сердечный привет жене. Ваш преданный М. Шагалл »

My thanks to Olga Makhroff and Marina Lewisch for the translation. - The exhibition Marc Chagall, Wassily Kandinsky, William Wauer included 38 paintings by Chagall, 28 by Kandinsky and 7 sculptures by Wauer.

- Other members of this circle included Albert Einstein, Oskar Kokoschka and Arnold Schoenberg. We should also point out that the fourth portfolio of the Bauhaus Italienische und russische Künstler editions (1922) included a Chagall engraving titled Self-Portrait with Woman.

- Letter from Marc Chagall to Pavel Ettinger, October 1936, published in English in Benjamin Harshav’s Marc Chagall and His Times: A Documentary Narrative, Stanford University Press, 2004, p. 451.

- Jean-Claude Marcadé, “Le contexte russe de l’oeuvre de Chagall,” in Chagall, 1984, pp. 18–25.

- Jean-Claude Marcadé, “Chagall et l’avant-garde russe,” in Chagall, 1995a, pp. 47–51, and also “Quelques aspects des liens de Chagall avec le monde russien,” Chagall connu et inconnu, Paris, RMN, 2003, pp. 57–61. For his relationship with Malevich, see Alexandra Schatskich’s “Chagall und Malevich in Witebsk,” in Chagall, 1991b, pp. 62–65.

- See La Russie et les Avant-gardes, Saint-Paul, Fondation Maeght, 2003.

- See Evguénia Pétrova and Jean-Claude Marcadé (ed.), La Russie à l’avant-garde: 1900–1935, Brussels, Palais des beaux-arts, Europalia International / Éditions Fonds Mercator, 2005. Chagall is represented by a single work, The Red Jew, painted in 1915, in a section entitled “L’art figuratif.”

- Alexander Kamenski, 1988, p. 365.

- See Boissel, 1995.

- See Brigitte Léal (ed.), Jacques Lipchitz dans les collections du Centre Pompidou–Musée national d’art moderne et du Musée des beaux-arts de Nancy, Paris, Éditions du Centre Pompidou, 2004.

- See Martin, 1980.

- Franz Meyer, Marc Chagall, Paris, Flammarion, 1995, p. 107.

- See Christian Derouet’s analysis, pp. 118–119.

- See Shatskikh, 2001, p. 27.

- See Germain Viatte, “Sur la constitution du fonds Larionov-Goncharova,” in Boissel, 1995, op. cit., p. 8.

Artistic Connections Between the Russian Empire and Europe in the Early 20th Century

Transated by: Rose B. Champagne

In 1900, the most important event in the French-Russian artistic relationship was the Paris International Exhibition, where Russia enjoyed an unprecedented place of prominence. Russia was represented by a total of five buildings, of which the Siberian Palace alone measured 4,900 square metres.1 The realism in the paintings of travelling artists was highly successful, particularly those of Apollinari and Viktor Vasnetsov, Isaac Lévitan and Léonide Pasternak. The most original contribution to the new art stemmed from the applied arts, the koustari (artisans), organized by the painter Maria Yakunchikova.2

Between 1906 and 1917, a whole host of artists and personalities linked Russia to Europe. Thanks to the inspirational work of Sergei Diaghilev, Europe discovered dance, music and the audacious paintings from Russia. The retrospective fall show that he organized in 1906, which encompassed 750 paintings representing Russian art from the 15th to the 20th century, exhibited the work of young painters such as Mikhail Larionov, Natalia Goncharova, Alexei Jawlensky, Pavel Kuznetsov and Léon Bakst, as well as “tapestries (naboïka) and carpets, the handiwork of Russian peasants.”3

The Russian artists were familiar with the most modern currents in modern European art thanks to exhibitions in the big cities of the Russian Empire and interactions with their European contemporaries on several occasions. In early 1909, the second Salon exhibit in Moscow called La Toison d’Or (Golden Fleece) displayed works from Georges Braque, including the famous Standing Nude, André Derain, Kees Van Dongen, Henri Le Fauconnier, Henri Matisse, Georges Rouault and Maurice de Vlaminck alongside works from Goncharova, Larionov and Martiros Sarian. The first Izdebski Salon, which opened in Odessa in 1909 and then travelled throughout the Russian Empire, highlighted Russian artists such as Nathan Altman, Aristarkh Lentulov, Ilia Machkov, Mikhail Matiouchine and Alexandra Exter, in addition to “Russians from Munich” like Marianne von Werefkin, Wassily Kandinsky and Alexei Jawlensky and some European artists, namely Pierre Bonnard, Giacomo Balla, Edouard Vuillard, Albert Gleizes, Maurice Denis, Jean Metzinger, Henri Rousseau and Paul Signac.

First-class artists from the Russian Empire who moved to Paris or Munich to study art enriched the heritage of international art: in Paris, Marc Chagall, Alexander Archipenko, Ossip Zadkine, Vladimir Baranoff-Rossiné, Léopold Survage; and in Munich, Kandinsky, von Werefkin, Jawlensky, Vladimir Bekhterev and Moise Kogan. Several of them made connections between Paris and St. Petersburg, Moscow or Kiev – Marie Vassilieff, baroness of Oettingen (alias François Angiboult), Sergei Yastrebtsov (alias Serge Férat), Sara Stern (alias Sonia Delaunay) and Jean Lébédeff – or brought back with them Parisian artistic novelties (cubist and futurist) – Exter, Yakulov, Altman, Lyubov Popova, Nadejda Oudaltsova and Véra Pestel in particular.

The renaissance of Russian art began to transition early in the 20th century into popular art, especially Slavic, one of the most varied and polymorphic in the world. Rare were the works from avant-garde Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Armenian or Georgian painters in the context of the Russian Empire, but then came Soviet Russia, which wasn’t exempt from the Primitivist movement and also encompassed Fauvist, Cubo-Futurist and Constructivist works.

In contrast to the refinement of symbolism, to the eclecticism of the modern style (which Russians called Art Nouveau), and to the realism of the travelling artists, what began to appear around 1907 – at the Stephanos4 Exhibition in Moscow – were forms and themes that were consciously and deliberately primitive, even vulgar, on the canvases of Larionov, Goncharova and the Burliuk brothers, David and Vladimir. Referred to as Neo-primitivism, this style of art drew its inspiration from children’s drawings, pastry tins, plates, stoneware squares, embroidery, secular and religious imagery, Izba wood sculptures, and elements that revitalized all concepts of art – laconism, non-conformism to scientific perspectives or to proportions, total freedom of drawing, the deconstruction of objects according to multiple points of view, simultaneity, an emphasis on expressiveness and humour, and on trivial and crude themes. The return to the “collective tradition” and the “national myth” started at the end of the 19th century, when they started studying the “treasures of popular creation sown in the depths of the Russian countryside.”5

It was in December 1909, at the third Salon exhibition of the Symbolist La Toison d’Or, where the Neo-primitivism of Larionov and Goncharova received a tremendous reception, amid popular works such as lace designs, lubki, Russian icons and Arabesque cakes. At that same time, Nikolai Koulbine was comparing the beauty in the art of prehistoric children and men to the creations of nature (flowers and crystals). That year Bakst, who had been Chagall’s teacher in St. Petersburg, also attracted attention with children’s drawings. Referring to the “new taste”, he observed that it “shows a primitive, uncommon form…a gross style, lapidary, the country table…a big chunk of bread seasoned with salt.”6 Children’s drawings were presented among works of art at the Izdebski Salon, which opened in Odessa in 1909, and would travel through numerous cities of the Russian Empire.

In 1912, Kandinsky organized the first lubki exhibition in Munich, at the Hanz Goltz Gallery.7 Presenting reprints of eight ancient xylographies (wood engravings) from his collection, he wrote: “These designs were made in Moscow, mainly in the first half of the 19th century (of course the origin of this tradition goes way back). Transient booksellers sold them even in remote villages. We can see them today on farms, even though they were often superseded by lithographs, chromolithographs, etc…”8 Der Blaue Reiter’s almanac shows a lot of children’s art and popular images from around the world – Russian, Bavarian, German, Chinese, African, Japanese, Brazilian, pre-Columbian, Egyptian, Polynesian. Kandinsky was very impressed with its discovery in 1888–1889, and how it reflected the artistic beauty of the Russian countryside and the Christian-pagan folklore of the Vologda region.9

It is therefore no coincidence that the author of Du Spirituel dans l’art (Spiritualism in Art), who resided in Moscow in the second half of 1910 and had contacts with the leaders of the art revival in Russia – and was also featured with German and Russian artists of the Munich Neue Künstlervereinigung at the first two Valet de Carreau (Jack of Diamonds) exhibitions in 1910 and 1912, asked David Burliuk to write an article for the Der Blaue Reiter almanac. The article would be titled “Die Wilden Russlands” (The Wild Beasts of Russia), in which Burliuk declared: “The law that Russian artists have recently discovered is only the re-establishment of a tradition that originates in the ‘barbaric’ works of art: those of the Egyptians, Assyrians, Scythians, etc… This rediscovered tradition is the two-edged sword that broke the chains of academic convention and set art free.”10

It was therefore logical that, following the publication of this article in Der Blaue Reiter, certain members of neo-primitivism would be invited to the second exhibition at the Goltz Gallery in Munich, held from February to April 1912. Invitees included the likes of Goncharova, Larionov and Malevich, members of a group of painters known as Donkey’s Tail who were becoming very successful in Moscow at that time thanks to an exhibition of their works. Some of these works of art ended up in the Kandinsky collection and can be found today in Paris at the Musée National d’Art Moderne (MNAM): the gouache Lumberjacks (1911) of Goncharova, Larionov’s Soldier’s Head (1911) and Malevich’s Study of Countrymen (1911), as well as Goncharova’s charcoal drawings of The Grape Harvest. These works are typical of the Russian neo-primitivism style in their over-simplicity of expression and their basic structure, borrowed from the lubok tradition rather than from “civilized” works. The Donkey’s Tail exhibition in Moscow11 was the first to feature a Chagall work – La Mort (The Dead Man) – in an avant-garde context. It was also in 1912 that Chagall’s work was exhibited at the Autumn Salon, and Yakov Tugendhold, a writer for the modernist publication St. Petersburg Apollon12, praised the young Chagall, saying his works are filled with “rich fire colours like the Russian countryside images, expressed to the grotesque, fantastic, to the limits of the irrational.”

It is thus not surprising that, in 1913, the Autumn Salon welcomed “Russian Popular Art in the image, the toy and the spice bread, an exhibition organized by Miss Nathalie Ehrenbourg.” These objects came mainly from the collections of members of the art world (Ivan Bilibine, Sergei Soudieikine, Nikolai Roerich, Sergei Tchekhonine), but also from the collections of avant-garde artists such as Koulbine, Exter and primarily Larionov. The catalogue cover for this exhibit was written by Tugendhold himself, reaffirming that “the contemporary cult of the primitive is different from the one of the romantic era and the orientalism era…. This archaic art, strong, expressive, forever young, brings hope of renewal, ‘rejuvenation’ to use Paul Gauguin’s word.”13

That same year Larionov organized an impressive exhibition of popular icons and images of Moscow. I. Ehrenburg (Ilia Lazarevich, a cousin of future Soviet author Ilya Grigoryevich Ehrenburg) quoted in a Paris-based Russian newspaper an article written by Alexandre Benois, which maintained that, to understand cubism, one must experience Russian icons and to understand the icons, one must experience cubism. He adds: “Our young Russian painters are not pure cubists. They have a lot of lubok and icon in them.”14

Thus, in the very early stages of the 20th century, primitivism made an indelible mark on Fauvism, Cézannism and Cubo-Futurism. The picturesque scenes of small-town life or religious rituals are transformed by conciseness, freshness, liveliness and the energy of age-old secular popular art. Chagall is particularly concerned by this. Tugendhold demonstrated in 1915 the importance of primitive art in Russia in his writings: “Chagall senses the imperceptible but terrible mystique of life. Those are the images of Vitebsk – a sullen, dull province, a modest hair salon, a lovers’ rendezvous a bit awkward under a misty moon and street sweepers, a dusty illusion of life on the streets of small villages. Chagall creates beautiful legends by capturing glimpses of the simple and common life.”15

- Exposition Universelle: Russia at the 1900 World Fair. Parijskaya gaziéta 9, 17 (4) (April 1900), 3.

- The Koustari of the Russian Section. Parijskaya gaziéta 10 (1900), 2–3.

- The Autumn Salon: Russian Art Exhibition. Exh. cat. with texts by Sergei Diaghilev and Alexandre Benois (Paris, 1906).

- The exhibition title was in Greek and referred to a collection of poems by Valéri Brioussov, also in Greek.

- Yakov Tugendhold, preface to Russian Popular Art in the image, the toy and the spice bread, an exhibition organized by Miss Nathalie Ehrenbourg. Autumn Salon 1913, exh. cat. (Paris: Kugelmann), 310.

- Léon Bakst, The Paths of Classicism in Art (Apollon 3, 1909).

- Lubok: Der russische Volksbilderbogen 1900–1930, exh. cat. (Munich: Münchner Stadtmuseum, 1985), 6–7.

- Cited in Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, Der Blaue Reiter Almanac (The Blue Rider Almanac) with notes by Klaus Lankheit (Paris: Klincksieck, 1981).

- See the original work, despite some extrapolations and minor errors, by Pegg Weiss, Kandinsky and Old Russia, The Artist as Ethnographer and Shaman (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1995).

- David Burliuk, The Russian Fauvists (1912), reproduced in Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, Der Blaue Reiter Almanac (The Blue Rider Almanac), 105–106.

- It consists of the cubist version of the painting The Dead Man (La Mort). Chagall’s first initial is erroneous in the exhibition catalogue (I.), which shows that the Vitebsk artist was not yet well known.

- Apollon 1, 1913.

- Yakov Tugendhold, preface to Popular Russian Art, 308.

- I. Ehrenburg, “Popular Russian Art in Paris,” The Parisian Messenger 20 (May 17, 1913).

- Yakov Tugendhold, “A New Talent,” The New Russians (Moscow, March 29, 1915), also cited in Marc Chagall, The Russian Years 1907–1922 (Paris: MAMVP, 1995), 242.

nbsp;

The Origins of Neo-primitivism in Chagall's Work

Transated by: Rose B. Champagne

It was in the summer of 1908 that Chagall began to draw and paint in a primitive and childlike fashion that would soon evolve into the fantastical, the style that would become his trademark, particular in later years when he would choose a vivid colour palette. It is often said that Chagall was influenced by Neo-primitivism which was very prevalent among avant-garde Russian artists of the time such as Mikhail Larionov, Natalia Goncharova and David Burliuk. However, being a Russian Jew of modest origins and a St. Petersburg student at the start of his career, Chagall would follow his own personal course, much different from that of his colleagues.

In June 1908, courses came to an end at the School of Imperial Society for the Fostering of Fine Arts, but Chagall remained in St. Petersburg to avoid being drafted in the czar’s army. Desperate letters to his patron, Baron David Ginzburg, and to his professor, Nikolai Roerich, demonstrate how much he dreaded this possibility, not only as an artist who would be obliged to end his studies but also as a Russian Jew whose life was threatened. Despite this fear, Chagall wished to leave the city and go home to Vitebsk, where “the sun calls me to the virgin scenery to draw” and where he wanted to “immerse himself in a sea of grass and in the bliss of the skies.”1 These metaphors, while specifically linked to his own personal situation, also express the notion that Russian artists and writers at the time wanted to differentiate themselves from symbolism and rediscover the values of nature and life in the countryside as sources of a new primitivism. In using these metaphors, Chagall proved that he was aligned with the prevailing currents of thought at the time.

In 1906, two articles titled “Colours and Words” and “Timeless” were published in Moscow’s glossy art review magazine La Toison d’Or (The Golden Fleece). In them, Alexander Blok, the famous Russian symbolist author whom Chagall knew well and whose writing the artist admired2, encouraged artists and writers to turn to childlike art, Russian nature and its people as a new source of creativity, because modern man had turned away from nature and had fallen into a mechanical lifestyle.3 This new attitude reached its highest peak in Blok’s 1908 article called “Three Questions” in which he insists on the importance of blending art and life.4 He asks artists to combine “the soul of a beautiful butterfly and the body of a useful camel” to show people “a new kind of free necessity [and] a conscious devotion to give words meaning and make the artist a man.”5

Such ideas certainly provoked debate at the School of Imperial Society, where Chagall had studied since 1907. A year earlier, painter Nikolai Roerich (1874–1947) was named director of the school and attempted to bring radical reform to the curriculum. He introduced art history, organized outings in the old Russian cities and put together workshops in decorative arts and crafts – ceramics, wood carvings, printing, weaving, glass painting, church paintings and later music and singing.6 He also invited sculptors, architects, critics and art historians, who were knowledgeable in the world of art and well informed with regards to developments in Moscow’s artistic scene, to teach his student artists. Therefore, Chagall’s teachers turned their attention towards Russian national heritage and modern influences. Russian symbolists such as Mikhail Vroubel and Viktor Borissov-Moussatov were among these influences, as was Japanese art and the work of Paul Gauguin.7

Roerich, a close acquaintance of Gauguin (whom he had met through Alexandre Benois while he was in Paris in 1901), had already experimented with this type of painting. He projected his admiration onto Chagall, who would find his own personal way of integrating Gauguin’s influence.8 As a result, he took an active role in the interaction between Russia and the French painter, especially after the Gauguin exhibit of 1906, which ran during the exact same time as the Russian exhibition organized by Sergei Diaghilev at the Autumn Salon in Paris. Furthermore, between 1908 and 1909, Nikolai Riabouchinski and his magazine La Toison d’Or (The Golden Fleece) presented Gauguin’s paintings in the major French-Russian exhibitions that he organized in Moscow. The French artist’s work was well represented in some of the most famous art collections in Moscow, such as the Chtchoukine and Morozov families. Consequently, the Moscow group “Goloubaïa Rosa” (The Blue Rose), which included artists Pavel Kuznetsov, Martiros Sarian, Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, appeared to be opening up their artwork to Gauguin’s influence as early as 1907–1908.9

Two of Chagall’s paintings around that time clearly demonstrate Gauguin’s influence: his Autoportrait au masque rouge (Self-Portrait in a Red Mask) and a painting that pictures his youngest sister titled Jeune fille au divan (Mariaska)” (Young Girl on a Sofa [Mariaska]) from 1907. Chagall’s own self-portrait is often compared to the works of Gauguin, such as his Autoportrait à l’idole (Idol Self-Portrait) of 1891, or his 1889 portrait, which was owned by the famous art collector Sergei Chtchoukine. Chagall at that time did not have a mustache or a beard; instead it seems as if these masculine symbols in his painting were influenced by the French painter. His irregular application of colours on a raw canvas, a technique used by Gauguin, shows how much Chagall identified with the wild French artist.

Moreover, his Young Girl on a Sofa recalls Gauguin’s Te Tiare Farani (Flowers of France) of 1891.10 The positioning of the subject on the left, in front of a flower vase painted against a flat wall, recalls Gauguin’s composition, while the person wearing a hat in the latter painting may have prompted Chagall to depict his sister with very short hair wearing an artist’s beret. Te Tiare Farani was shown at the 1906 Gauguin retrospective in Paris and bought in 1908 by Ivan Morozov.11 It is not known with complete certainty that Chagall went to Moscow to view the French-Russian exhibitions or private collections, but the modern teachings of his school allow us to speculate that the students may have visited the city as well as its collections and exhibitions while on an organized visit.12 Nevertheless, Chagall’s work reveals without a doubt that he had intimate knowledge of Gauguin, most likely passed on by Roerich, possibly by means of photographs.

However, in the two paintings mentioned above, a number of other influences are palpable which, in 1908, played an important role in the development of Chagall’s primitivist style. The most important ones stem from avant-garde theatre and childlike art. The red mask that Chagall removes from his face in his self-portrait recalls creations from some artists of the World of Art, such as Konstantin Somov, containing visual references to the commedia dell’arte revival, to street theatre and to the flourishing political satire in St. Petersburg after 1905. Alexander Blok is one of the first to use the theme of the “commedia dell’arte” in his Balagantchik (The Booth at the Fair), a play adapted from his 1905 poem. The famous director Vsevolod Meyerhold produced it in St. Petersburg in 1906 and again in 1908, in the imperial theatres where it met with great success.

Chagall is certainly aware of Somov’s coverage of the works that Blok published in 1908.13 In his self-portrait, Chagall turns his head to the right (where a frivolous woman is seen on Somov’s cover), has a red mask (which matches the woman’s dress) and portrays himself with curls on his forehead looking like horns, a slightly hooked nose, a mustache with a goatee and a pointed ear. Here he seems to be identifying himself in a devilish manner or as a Pan-like character – typical of the renewed theatre. Again, the work seems to recall Gauguin’s (as well as Nietzsche’s) appeals to abandon modern civilization and return to his roots, in other words to leave St. Petersburg and return to Vitebsk where he could free himself from the old art forms saturated with western traditions, both classical and Christian, and to adopt the new primitive art form rooted in the Jewish folklore of the countryside.

Young Girl on a Sofa seems to be the first example where Chagall applies his new artistic orientation and is one of numerous intimate portraits that Chagall made of his family. By representing his youngest sister in a clumsy, childish style, he already gives a glimpse of the free and fresh direction he is about to take. The influence of the theatre, as well as Gauguin, seem to play a crucial role by means of Maurice Maeterlinck’s Blue Bird.14 Some important aspects of this play, first written as a children’s story, reinforce Chagall’s decision to develop his new style. The play introduces a fantastical universe of imagination and a new way to look at the world, which Chagall produces in an equally new fashion – Mariaska’s proportions are distorted, and her limbs are flat and surrounded by a thick dark outline, like a child’s drawing which she could have made herself.

In April of 1908, Léon Bakst, member of the World of Art and future teacher to Chagall at the prestigious Zvantséva School, remarked on the importance of primitive and childlike art at a conference called “Paintings of the Future and its Relationship to Antique Art” at St. Petersburg’s Theatre Club.15 In May of 1907, Bakst and the painter Valentin Sérov travelled to Greece where they discovered Greek archaic art which influenced them deeply and prompted Bakst to question and rethink his impression of classical art. The new ideas he generated on this trip prompted Bakst to contemplate the “art of the future” as seen in children’s paintings: spontaneous, filled with colours and emotions.

For Bakst, there were common traits in popular and archaic art, but also in the works of Gauguin, Matisse and Denis.16 He praised the symbolic qualities of these art forms which elevated daily objects to a symbolic or abstract level, in the same way as childlike and primitive art. However, he proposed formal ways to get there: future artists would have to become bold, simple, impolite and primitive. The art of the future must develop “a rough style because new art cannot include refinement…. Art of the future must stem from the deepest grossness.”17 Chagall must have attended this conference and been seduced by the modernist theme of his talk. It was probably for this reason that Chagall contacted Bakst later that same year and decided to study with him at the Zvantséva School.

In addition to his theoretical debates, concrete examples also encouraged Chagall to develop his new childlike style. In the spring of 1908, an article was published in the weekly magazine Theatre and Art by the critic Alexandre Rostislavov titled “Children and Adult Art.” He mentions the childlike art exhibit from the New Society of Artists alongside an exhibition of works from artists of the World of Art (namely Benois, Yevgeny Lanceray, Mstislav Dobujinski, Boris Kustodiev and Alexandre Golovine). Rostislavov saw a form of primitive art that was lacking technique but revealed a “wonderful side, mysterious, magical [artistic] creation…. Children’s art, even with its total absence of technique, excites us, we laugh at its innocence, we even envy it.”18 This may have been the time that Chagall began collecting drawings by Mariaska to study and use as a source of inspiration. In his 1909–1910 sketch pad, there appears a simple child’s drawing, a stick man which, according to Chagall’s notes, was made by his sister Mariaska.19

Chagall already felt free to use this type of childlike art and to start applying it to serious subjects, as well as to illustrate, in the detached manner of children, the complex and often painful reality of the lives of Russian Jews in the early 20th century. Thus, he used this style to deal with problems such as the family life of Jews divided between the traditional and modern lifestyle (The Dining Room and The Room on Gorokhova Street, both from 1910), love and marriage, in which strict religious rules are questioned (The Ball of 1908, The Wedding of 1908–1909, The Couple at the Table of 1909, The Aunt’s Wedding of 1909–1910, and The Mikveh of 1910), and death which is often a consequence of anti-Semitic attacks, persecution and pogroms (The Village Fair of 1908, The Dead Man of 1908–1909, and The Event of 1908–1909). In this way, Chagall combines the social consciousness of his first teacher, Yéhouda Pen (and other Russian and Polish Jewish artists from whom he discovered Realist and Impressionist art in Vitebsk in 1906–190720) and his new primitivism style. To this art, which often deals with traditional Jewish life in Eastern Europe, he added the modernist style that emerged at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Starting in the fall of 1908, he integrated into this modern style numerous elements of Yiddish popular culture which drew from detailed studies by intellectuals involved in the revival of the Jewish culture. Their work centred around the activities of historical and ethnic Jewish society, created by the Russian Jewish ethnographer and author Semyon Anski (born Shlomo Rappoport) who was born in Vitebsk. Thanks to this society, which collected Jewish religious objects, published proverbs, lullabies and Hasidic stories, and described Jewish traditions and customs in the cycle of life, Chagall understood the importance of this material and became more aware of his role in the Yiddish popular tradition and culture, which he knew well.21

The Dead Man is a good example of a work that fuses several worlds on different levels while amazing the spectator with its primitive and crude quality. Several authors found influences in the theatre, the childlike imagination, the Yiddish traditions and the harsh realities of Russian-Jewish history. However, we may recall the comments expressed by Maximilian Syrkine, a Russian-Jewish art critic who first commented in 1916 on certain unusual aspects of The Dead Man, namely the presence of the violinist sitting on the roof. Calling this painting “fantastical-humorous,” he saw in the violinist “the soul” of the dead, dressed in a worn jacket and cap, happy to be free from his Jewish destiny and his transitional existence.”22 In his own 1908 article, Blok asked Chagall to demonstrate to the world “a new kind of free necessity [and] a conscious devotion to give words meaning and make the artist a man.”23 He added that popular art and folklore songs do exactly that by combining beauty and usefulness, art and work by means of rhythm.24 Therefore, this essential musical element becomes a unifying element. In adding the image of a violinist – a Jewish klezmer – to his painting, Chagall invites us to imagine his music and introduces the unifying element that connects the complex worlds to which he belongs.25

While summarizing Chagall’s artistic evolution, The Dead Man also introduces a novelty: the yellow-green colour of the sky, indicating new influences that he acquired from Bakst’s teachings. According to Iulia Léonidovna Obolenskaia, a former student at the Zvantséva School where Chagall began to study in 1909, Bakst explained that the source of all composition stems from the relationship between colours.26 He encouraged this new art form with his students and taught them to appreciate Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse and Maurice Denis. Bakst also expressed his ideas in public conferences and in his writings, and in the fall of 1909, Apollon magazine published his conference “Painting of the Future and its Relationship to Antique Art,” which was held in April 1908, and was likely the main impetus for Chagall to study with Bakst. The author admired the elementary forms of childlike drawings, but above all he valued their bright and strong colours. In his view, pure and strong colours are totally natural since they exist in the animal world – particularly birds and butterflies – and in flowers. As such, he felt it was absolutely natural that young children or archaic and popular artists not influenced by rules of “good taste” would use such colours.27 In recommending the use of bold colours and sustained tones, Bakst hoped to encourage his students toward a new path.

Likewise, Chagall may have discovered the Fauvists in Moscow. In January or February 1909, he may have seen, in the French section of the exhibition of La Toison d’Or (The Golden Fleece), works from Derain, Vlaminck, Friesz, Marquet, Matisse, Van Dongen or Braque, whose pre-Fauvist, Fauvist and pre-Cubist paintings were on display.28 This exhibition, like the previous one29, would bring in thousands of art enthusiasts30 and, while Chagall was still studying with Roerich at the time, he probably travelled to Moscow with his class and had the opportunity afterwards to view the Chtchoukine collection. He may have also viewed some of Matisse’s Fauvist paintings, in particular La Desserte rouge (The Dessert: Harmony in Red [The Red Room]) from 1908.31

According to Obolenskaia’s memoires, one of Chagall’s first paintings in accordance with Bakst’s teachings, was a “study in pink on green background,” a title that describes the subject as a combination of colours, which the teacher might have appreciated.32 His first painting to be exhibited with bold colours appeared in the “Petit Salon” in 1909. It would take some time for him to accept this novelty, but starting in 1911 colour would become one of the main elements of his paintings. We conclude this analysis with The Father (or Bearded Man) of 1911, in which Chagall depicts his father as a traditional Russian Jew, bearded and posing in an autumn landscape. In this work, Chagall combines multiple sources that encompass his Primitivist style: the raw characteristics of childlike art, his small-town Jewish roots, his love of nature and his colour combinations which were strongly influenced by Fauvism.

- Letter to Nikolai Roerich from Marc Chagall, in Chagall 1995a, 238; Marc Chagall and Kh. Firin, “A Suffering Painter Can Understand Me,” in Peterbourgskie gody M. Z. Chagala (Chagall’s Petersburg Years), Iskousstvo Léningrada 8 (1990), letters 3 and 6, 107–108.

- On Chagall’s admiration for the poet, see Franz Meyer, Chagall, Life and Work (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1963) 243, or the French Edition (Paris: Flammarion, [1964] 1995).

- Alexandre Blok, “Colours and Words,” in Zolotoie rouno (The Golden Fleece) 1 (1906), 98–103; “Timeless,” in Zolotoie rouno (The Golden Fleece) 11–12, 107–114 [Alexandre Blok, Sobranié sotchinenii (Works) (Moscow-Leningrad, 1960), vol. 5, 19–24, 66–82].

- Alexandre Blok, “Three Questions,” in Zolotoie rouno (The Golden Fleece) 2 (1908), 55–59. Analysis of this essay and the ones from 1906 are found in William Richardson, Zolotoe Runo and Russian Modernism: 1905-1910 (Ann Arbor, 1986), 106–109.

- William Richardson, Zolotoe Runo, op. cit., 111.

- Jacqueline Decter and Nicholas Roerich, The Life and Art of a Russian Master (London: Park Street Press, 1989), 67.

- Ibid., 38–39.

- On the importance of Gauguin for Chagall, see Franz Meyer, Chagall, op. cit., 14 and 71.

- Concerning Gauguin’s influence on these artists, see Marina Bessonova, “Paul Gauguin and Russian Avant-Garde Art,” exh. cat. (Ferrare: Palazzo dei Diamanti, 1 April – 2 July 1995), 259–277.

- See Franz Meyer, Chagall, op. cit., 73, and Bessonova, Russian Avant-Garde Art, op. cit., 67.

- Ibid., 66.

- In his autobiography, Chagall – during a conversation with a French lady travelling by train in 1914 while he is returning to Russia – states: “Personally, I have only seen Petrograd, Moscow, the small suburb of Lyozna and Vitebsk.” Marc Chagall, My Life, translated by Bella Chagall, Paris [1923], Stock 2003, 166. As far as residing in Paris between 1911 and 1914, here he alludes to his life in Russia before moving to France.

- Spencer Golub, Evreinov: The Theatre of Paradox and Transformation (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1984), 2, no. 4. Somov created the cover for Alexandre Blok’s work, “Lyrical Drama, The Fair Stand, The King in the Square, The Stranger”, St. Petersburg Theatre Series, 1908.

- Chagall most likely attended this play in St. Petersburg in the spring of 1908, performed by the Kaminski Company which was made up of the Warsaw Yiddish Theatre. See also I. Turkow Goldberg, Di Mame Ester Rachel (Warsaw, 1953), 194–220 (in Yiddish).

- Irina Pruzhan and Léon Bakst, Set and Costume Design, Book Illustrations (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1988), 220. The conference paper was published in November 1909, in Léon Bakst “The Paths of Classicism in Art,” Apollon 2, 63–78, and Apollon 3, 46–62.

- Léon Bakst, “Pouti Klassitsizma v iskousstve,” cited in Apollon 3, 54–61.

- Ibid., 60–61.

- Alexandre Rotislavov, “Children and Adult Art,” Teatr i iskusstvo (Theatre and Art) 9 (1908) 170–171.

- I wish to thank Mrs. Miriam Cendrars for giving me permission to view, in the fall of 1995, Chagall’s 1909–1910 sketching book, which is part of her collection.

- Among these artists are Isaak Asknazy, Moses Maimon, Samuel Hirszenberg and Léonide Pasternak.

- Ziva Amishai-Maisels, “Chagall and the Jewish Revival: Center of Periphery?” in Ruth Apter-Gabriel, ed., Tradition and Revolution: The Jewish Renaissance in Russian Avant-Garde Art, 1912–1928 (Jerusalem: Israel Museum, June 1987), 71–100, and Mirjam Rajner, “A Parokhet as a Picture: Chagall’s 1908–1909 Prayer Desk,” in Studia Rosenthaliana 37 (2004), 193–222.

- Maximilian Syrkine, “Marc Chagall,” in Evreïskaïa nedelia (The Jewish Week) 20 (15 May 1916), 44.

- See note 5 of this text.

- William Richardson, Zolotoe Runo 27, 111.

- Mirjam Rajner, “Chagall’s Fiddler,” in Ars Judaica, The Bar-Ilan Journal of Jewish Art, vol. 1 (2005), 117–132.

- Iulia Léonidovna Obolenskaia, V chkole Zvantsevoi pod rukovodstvom L. Baksta i M. Dobouzjinskovo, 1906–1910 (At the Zvantséva School, Directed by L. Bakst and M. Doboujinski, 1906–1910) (Moscow: Trétiakov National Gallery Department of Manuscripts, fonds 5, stock 75, sheet 15). Some parts of this text were translated into English and used by Franz Meyer, Chagall, op. cit., 59–60, and I. Pruzhan, Bakst, op. cit., 16, 219.

- Léon Bakst, “Pouti klassitsizma v iskousstve,” cited in Apollon 3, 54–56.

- William Richardson, Zolotoe Runo, op. cit., 144–146; Zolotoie rouno 1 (1909), 15–18, and Zolotoie rouno 2–3 (1909), 3–30. The January and February/March issues of this magazine contained reproductions of his works in black and white.

- The French-Russian exhibition in Moscow organized by La Toison d’Or (The Golden Fleece) in 1908.

- Zolotoie rouno 2–3 (1909), 116.

- Chtchoukine bought all these paintings over the course of the year 1908, and by early 1909 they were part of his collection. See Albert Kostenevich and Natalia Semenova, Matisse v Rossii (Matisse in Russia) (Moscow, 1993), 73, 77, 162. See also A. Izerghina, Henri Matisse, Painting and Sculptures in Soviet Museums (Leningrad: Aurora Art, 1978), 138–139.

- Franz Meyer, Chagall, op. cit., 60.

Goncharova, Larionov and the Limits of Cubism

In the autumn of 1913, a period of increasing social unrest and political turmoil, the prominent avant-garde artist Natalia Goncharova issued a surprising challenge to her critics. In a draft of what became the catalogue essay for her mammoth 1913 Moscow retrospective, she rejected the subjectivist aesthetics that so many associated with an alienated modernism. Opposing “the trivialized and decadent sermons of individualism,” she declared her readiness to use “all contemporary accomplishments and discoveries in the realm of art,” particularly Rayonism (“a new form of art and life” and “the pure doctrine of painting”) promoted by her companion, painter and avant-garde impresario Mikhail Larionov. Yet practically in the same breath, she proclaimed her unique proclivity as an artist to absorb all impressions and types of experience – even the most banal. For Goncharova, subjectivity is shaped by the society that nurtures it, and motivation found in the “bright, unpretentious reception of all that surrounds me, and a specific attitude to all things. That is, having studied the views circulating in society and winnowed through upbringing, I am free.” She concluded that the era of art theory and debate had ended – it was time “to appeal directly to the streets, to the popular masses in general.”1

These were the paradoxical conditions of modernist art in Russia during the decade when Chagall was working in a different centre, namely Paris. In their most fruitful phases, the careers of both Goncharova and Chagall pitched between Moscow, St. Petersburg and Paris, obliterating the centre-periphery hierarchy. During this time, their open orientation to diverse cultures prevented critics from settling comfortably on either historical period or personal style to represent their art. Indeed, Goncharova’s Cubism and Futurism was nearly as questionable as Chagall’s – if we limit ourselves to a particular kind of formalist interpretation. It is even more difficult to speak of Cubism in Larionov’s progression, despite his careful reading of its history. Yet all three were engaged in exploration of the material-formal principles associated with Cubism and, especially in Larionov and Goncharova’s case, Futurism. Their tangential approach to style as a marker of identity and creative purpose distinguished their projects from what became the mainstream of Modernist art, both Russian and Parisian.