Painting a public archive

Veteran Toronto muralist John Kuna gets candid about the Islington Village Mural Project and his practice at large.

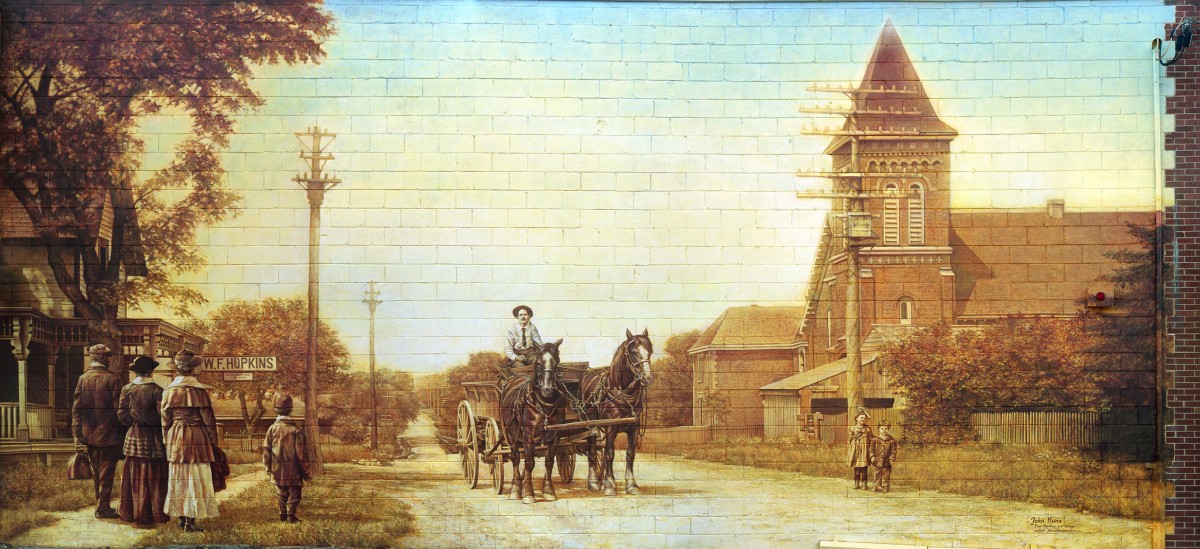

John Kuna, Islington Mosaic Heritage Mural Project, mural #13, 2010. Acrylic latex on stucco, 21 x 26 feet.

The Islington Village Mural Project is a massive community-based beautification effort funded by the City of Toronto, spanning roughly five blocks of West Toronto’s Islington village. The project comprises 26 large murals created between 2005 and 2018, each commemorating an historic moment in Toronto from the 19th and 20th centuries.

Veteran muralist John Kuna painted 80 per cent of the entire project, incorporating a striking conceptual flair in many of the commemorative works. His unique depiction of Islington Junior Middle School features an evolving spectrum of group graduation photos that range from the class of 1899 to the class of 2000. An accomplished public artist, Kuna has been commissioned to complete murals in over 40 cities in Canada and abroad.

We recently spoke to Kuna about the Islington Mural Project, his practice and public art philosophy.

AGOinsider: The Islington Village Mural Project is massive. How long did it take you to complete? Did you work with a team? Is there a particular piece of Toronto history you learned while working on the project that significantly impacted or interested you?

Kuna: The first mural I was commissioned to do in the Islington neighbourhood was in 2005. I have completed the last one in 2018. About 80 per cent of the pieces were painted by myself. I would seek the help of colleagues whose workmanship I trust whenever I started to fear that the work would not get done before the weather turned bad in November.

I don’t think a particular aspect of this city’s history has impacted me as much as perceiving that history as a whole. Through the work, one acquires a perspective into how a city changes over time, how it transforms in terms of geography, demographics and identity. That's really the importance of a project like the Islington murals. It has didactic value. It shows people that the ground they walk on used to be something else. Islington is not directly the site of major historical events and yet there are stories there that form a narrative of how a small settlement became a town, which was eventually integrated into one of the largest, uninterrupted urban landscapes in the country.

AGOinsider: You’ve said before that a good mural “must assume an awareness of the nature and character of the environment it intends to be part of.” Can you elaborate on what this statement means to you?

Kuna: The statement refers to principles when beginning to design a mural. The first is thematic. For people who will live with that artwork on a near-daily basis, decisions must be made on how I would want them to see it. How do I want the themes communicated? Should the artwork be bold or subtle? Should it be enigmatic, esoteric or should it be direct and easily approachable? I have gotten to know the people in Islington very well over the years. I wanted most of that work to be universally accessible in order to draw the viewer in and make the individual parts understood as part of a narrative.

The second principle is aesthetic. A mural isn't an autonomous canvas against the blank wall. It is part of a dynamic three-dimensional landscape. Therefore, I create my designs to fit that space specifically using photographic templates. This allows me to make decisions with an awareness of every architectural detail that will frame the painting once it is finished. I have never believed that a mural should be something one designs in a vacuum and then throws up on a wall in the hopes that it will stick.

AGOinsider: If you could paint a mural on any surface in the world, where would it be any why?

Kuna: If there is a surface in the world, whether natural or man-made, that I have a particular fondness for, I would probably not wish to alter it. I think the act of mural-making is mostly about wanting to fill an emptiness. Here in Toronto, a city that has since the 1960s steadily divested itself of its architectural heritage with little concern for urban planning, we are currently left with a lot of that kind of emptiness. There was certainly a lot of it in Islington.

Having said that, I always had this fantasy of painting a mural on a massive glass ceiling. The ceiling would be made up of overlapping panes of glass each painted with semi-transparent pigments like stained glass windows stacked upon one another. The work would change with the light of day and according to which direction you looked at it.

AGOinsider: As a muralist with so many commissioned public works, what are your thoughts about traditional street art/graffiti culture and artists who choose to create public art freely, without sanction?

Kuna: I always liked the look of graffiti. Even when it is made up of just overlapping tags it creates this ecstatic whole, greater than the sum of its parts. But it is again about filling an emptiness. I like it when it surprises you on a drab street corner in Toronto. I do not like it when it surprises you on the wall of a 400-year-old church in Prague. Ultimately, graffiti is like any art. Some of it is brilliant and some of it is not. Sometimes it communicates with you and sometimes it's just noise.

In Toronto, we seem to have an interesting situation where graffiti art has been legitimized through programs like STEPS and StArt. Talented graffiti artists have finally been given publicly sanctioned space to do their work and they have been well compensated financially. As a result, I have seen the overall standard of street art improve in this city and it has given us some international quality murals. However, it seems to have also split the graffiti community between those whose work is good enough to be publicly recognized and those whose work isn't. In the last couple of years, I've seen some of my favourite graffiti murals directly targeted by taggers. This is fairly new since the graffiti community generally adheres to ethical guidelines discouraging that level of disrespect. Once the weather permits, I myself have to return to Islington where someone has just tagged over most of the ground-level details in five key murals. This is the first time in 20-odd years that something like this has been done to my work. I have estimated the repairs to take a minimum of three weeks. In the end, I can’t say that this act has altered my view of graffiti as I do not consider the perpetrators either graffiti or artists. The only thing their statement seems to communicate is the well-understood fact that it only takes a few minutes to destroy something it took months to create