Becoming a dress detective

Toronto’s own ‘Dress Detective’, Ingrid Mida, returns with a new book that investigates how the body is fashioned in art.

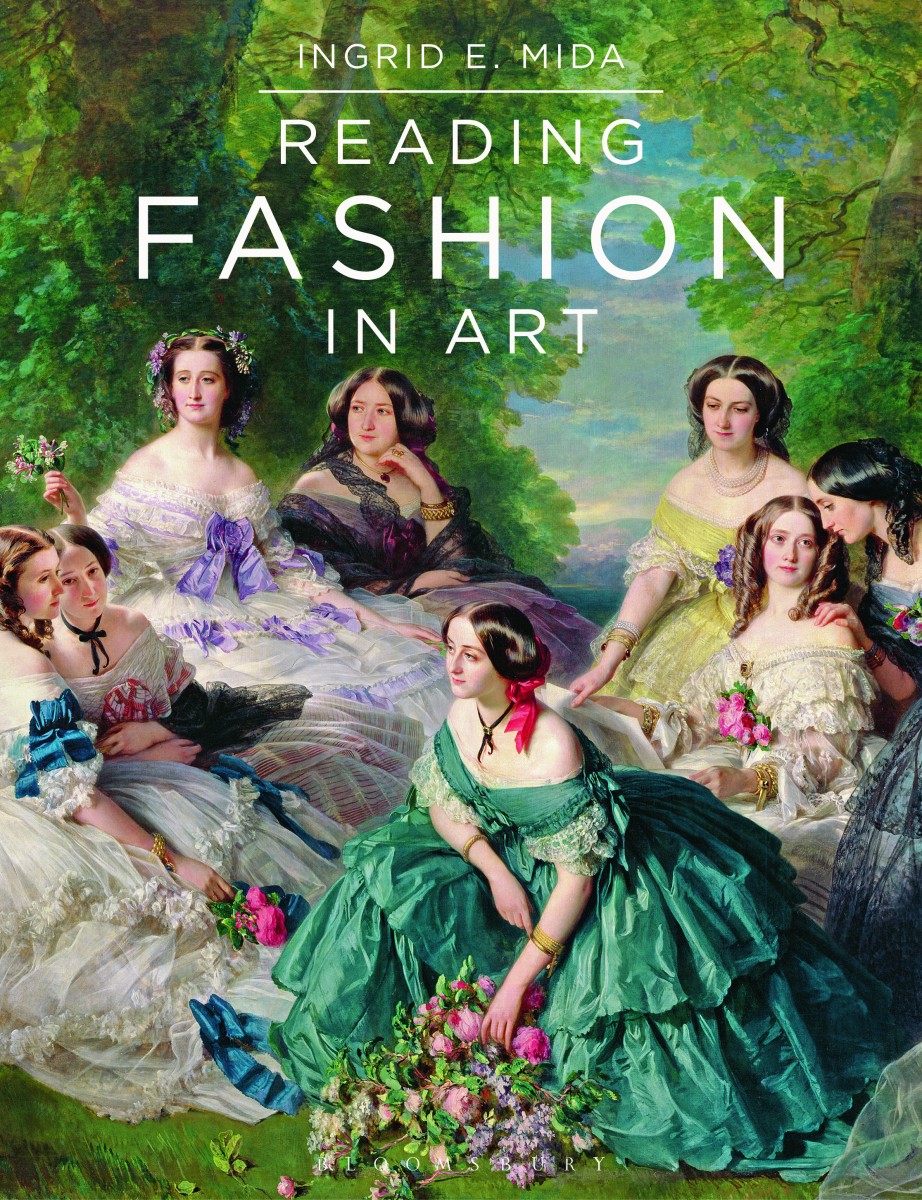

While florals for spring may not be groundbreaking, Ingrid Mida’s latest book about fashion in art is au courant. Dress and fashion are ever-changing, offering important clues for our understanding of artworks. For aspiring dress detectives everywhere, author and scholar Mida presents Reading Fashion in Art, an essential handbook in the toolkit for art analysis.

We recently sat down with Ingrid Mida to learn more about her latest book, Reading Fashion in Art.

AGOinsider: Reading Fashion in Art draws on artworks from museum collections around the world, including the AGO. What were the criteria that led you to choose the featured artworks?

Mida: The underlying premise of Reading Fashion in Art is that dress and fashion are central to our understanding of figurative art, since the way that the body is fashioned provides meaningful clues as to the cultural beliefs of the time in which artworks were produced. The works selected for the book illustrate the intersection of fashion with the themes of identity, modernity, beauty, gender and politics. I aimed to find a balance between works that people might be familiar with, such as Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews or Tissot’s Shop Girl, alongside less well-known works by artists representative of our globally diverse world, including Black, Indigenous and People of Colour, disabled and queer communities such as Yinka Shonibare’s Mr. and Mrs. Andrews Without Their Heads (1998), Kent Monkman’s 2008 painting The Academy, and Mickalene Thomas’s 2010 painting Les déjeuner sur l’herbe: Les trois femmes noires.

AGOinsider: Your book provides readers with a clear step-by-step guide to analyzing dress in art. In light of your research, what is the most essential step to understanding fashion in art?

Mida: My book provides a template for a critical reading of fashion and art. I cannot really reduce this to a single step, but I do encourage people to adopt the slow approach to seeing. This involves an extended period of time of looking at an object – whether that is a dress or an artwork. In this book and in my previous book, The Dress Detective, I argue that there is a difference between looking and seeing, since we can look but not see. The main idea is to enact a process that helps one look long enough to see the subtle details or clues that can reveal the meaning behind the way the artist has fashioned the body.

AGOinsider: Can you clarify the important distinction between fashion and dress for us?

Mida: Fashion is ever changing and only looks right at a particular time and place. Although the words are often used interchangeably, there is an important distinction. The word dress is generally used to describe the clothing that conceals or reveals the body whereas the word fashion is used to describe the prevailing or preferred manner in which the body is presented at any given time. In other words, you can be dressed but not be in fashion. An artist can choose to depict the figure wearing fashionable clothing or not and understanding that distinction is helpful in unraveling the underlying meaning of the work.

AGOinsider: Do you have a favourite outfit in art history?

Mida: That is a really tough question for an art and dress historian. I am a long-time fan of the work of the nineteenth-century artist James Jacques Tissot, who was known for his meticulous attention to the details of fashion and I have studied many of his exquisite etchings in the AGO Collection. However, I also really admire the pale blue silk satin gown trimmed with delicate lace worn by Adélaide Labille-Guiard in her 1785 self-portrait (included in my book as Figure 1.2) because it is such an impractical choice to wear while painting that I cannot help but appreciate this choice.

AGOinsider: You were recently invited by AGO curators Adam Levine and Monique Johnson to discuss the Portrait of a Lady with an Orange Blossom investigation. What, in your mind, is the most striking part of her dress?

Mida: For me, the way the dress is accessorized is striking. The neckline and sleeves of the dress are trimmed with bands of trim edged in silver and the dress apron and fichu are made of a very fine translucent silk gauze. These details would have been costly and are signals of wealth and status.

AGOinsider: You are credited with reviving the Ryerson Fashion Research Collection. Why was this important to you?

Mida: When I undertook to revive the Ryerson Fashion Research Collection in 2012, it was housed behind an unmarked door of the library, had been dormant for several years, was uncatalogued and was unknown by the student body. I saw a hidden gem that would allow students to learn and practice the skills of object-based analysis, examining the garments to reveal the stories hidden within them; very like the stories hidden within art. So much can be learned from studying an object in-person and in detail. Making collections accessible and helping students, budding curators and anyone interested in learning the skills of object-based research is important to me and that is why I wrote The Dress Detective and also Reading Fashion in Art.

Are you an AGOinsider yet? If not, sign up to have stories like these delivered straight to your inbox every week