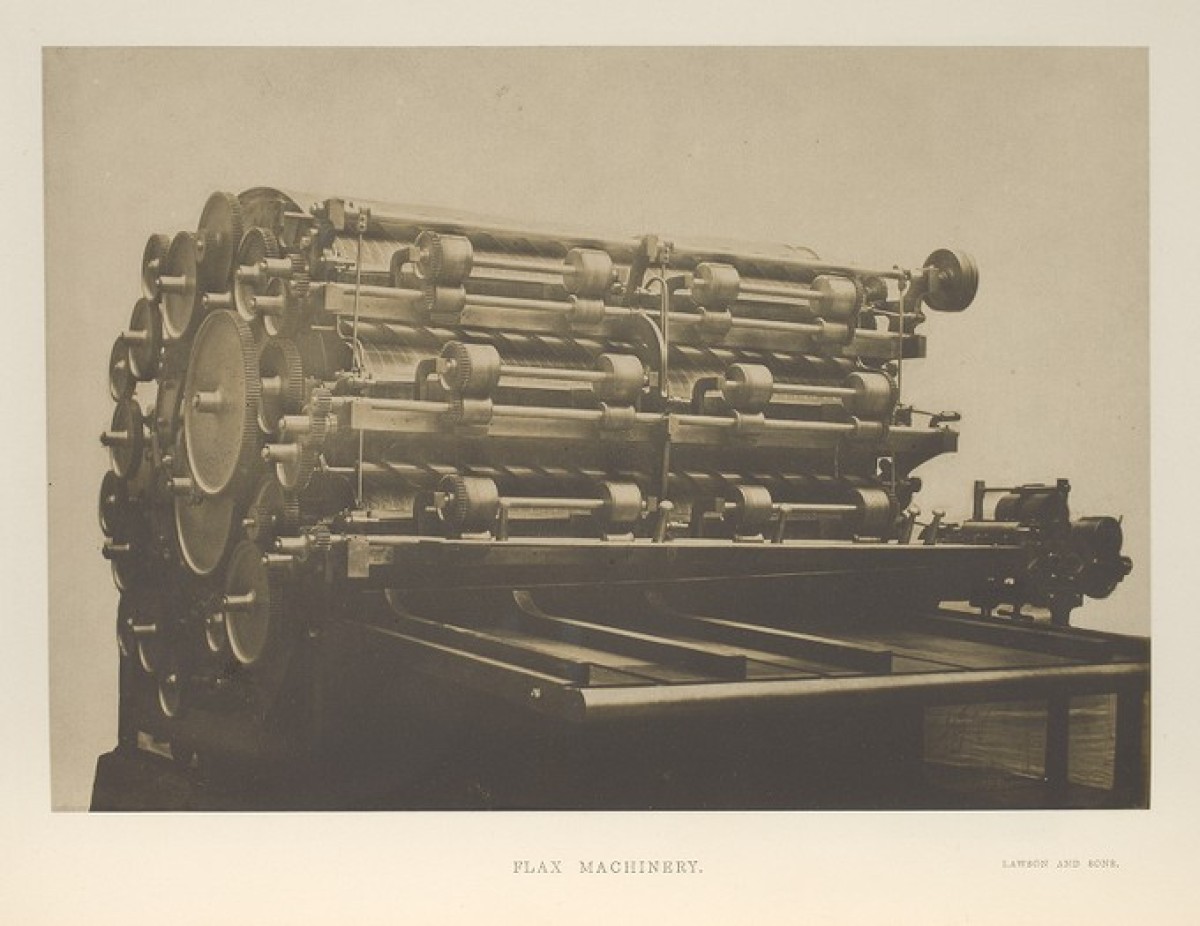

Flax machine

Weft in time for summer, we loom in on ancient fabric for the latest in our ongoing series of material explorations.

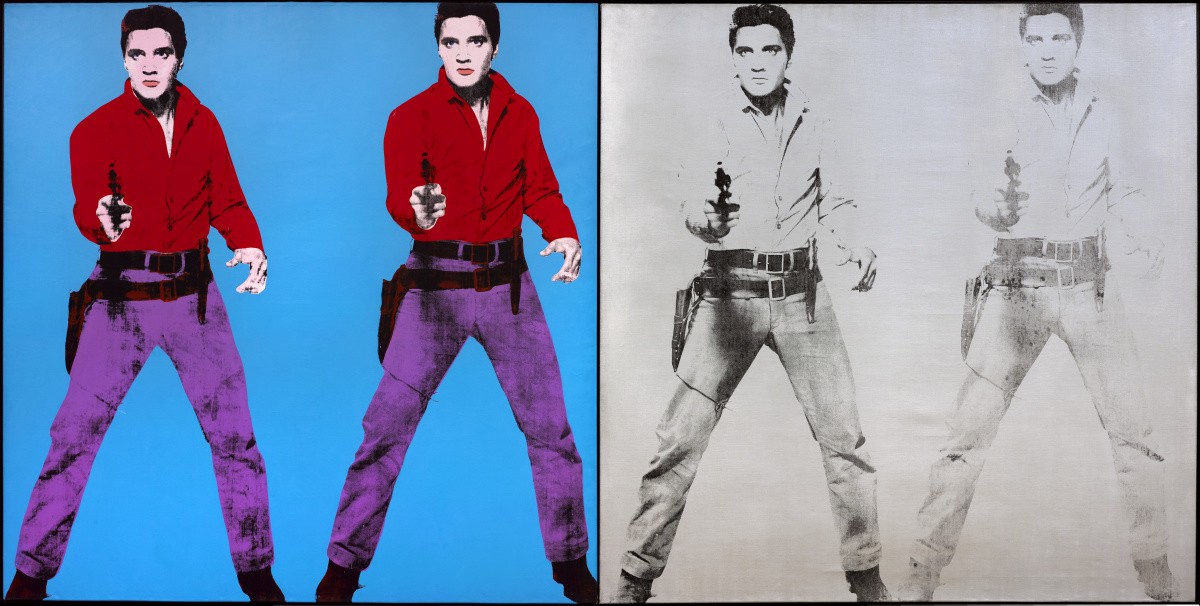

Andy Warhol. Elvis I and II, 1964. Silkscreen ink and spray paint (silver canvas); silkscreen ink and acrylic (blue canvas) on linen, Framed (overall): 213.5 × 422 cm. Gift from the Women's Committee Fund, 1966. © 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOCAN

It was esteemed French film director François Truffaut who said, “airing one's dirty linen never makes a masterpiece.” But what about clean linen? Surely it’s good for something? Freshly pressed, we set out to explore the AGO Collection in search of linen masterpieces.

Strong, quick to dry and cool to the skin, linen has been synonymous with soft sheets and summer fashion since the ancient Egyptians. It was 4,000 BC when they began commercial-scale production, creating 500 thread count clothing, sails, upholstery and funerary materials. By 900 BC, Phoenician traders were sailing to Northern Europe and the British Isles, trading Egyptian linen for tin, and it wasn’t long after that the Romans set up weaving mills across Britain and Western Europe to supply their colonial armies. The rich soil and frequent rain in Northern France, Belgium, Ireland and the Netherlands uniquely suit the flax plant, which, once harvested and processed, results in the highest-quality linen cloth.

We begin our tour with a visit to the AGO’s Conservation laboratory, where Meaghan Monaghan, the AGO’s conservator of paintings, is stacking bolts of fabric.

“Linen,” she says, “is the basis for most surviving historical paintings, and we keep some on hand in case we need to patch a painting or to support artworks whose fabric supports are fragile. Paolo Uccello’s painting Saint George and the Dragon, from 1470, has the distinction of being the world’s oldest-known surviving painting on linen. It’s not surprising that no earlier artworks remain considering how susceptible linen is to degradation through exposure to water, light and mold. It’s a highly absorbent material, so it will hold smells, humidity and environmental pollutants. And ironically, despite being so absorbent, it doesn’t dye very well. The darkness of the fibres makes it very difficult, even with bleach, to achieve a pure white colour. Today, cotton is more commonly used in artist supports because it is affordable, durable, flexible and much easier to bleach white.”

With so many paintings described simply as an oil on canvas, how does Monaghan know which are on linen?

“Under a microscope,” Monaghan says, “it’s very easy to tell what material a painting is on. Whereas cotton fibres are twisty, short and colourless, flax fibres are long and even, with little bumps called nodes. On account of those nodes, traditionally linen has a much more textured surface than cotton, which artists went to great lengths to smooth over, with layers of lead paint. Today of course, many artists see that texture as an aesthetic advantage.”

To Monaghan’s left, recovering from its sojourn at Tate Modern and preparing for its return to the limelight when Andy Warhol opens this summer, is the AGO’s own Elvis I and II from 1963. Acquired in 1966 by the AGO Women’s Committee, it’s a massive artwork, more than four metres wide, done on linen canvas. As with Silver Liz as Cleopatra (1963) the AGO’s other massive Warhol celebrity portrait, the artist applied silver paint directly onto linen, and then silkscreened an image on top of that. No attempt has been made to cover the textured nature of the linen surface or to pretend the artwork is a pristine creation. As Warhol's biographers Tony Scherman and David Dalton point out, Warhol "was not after a picture-perfect, sharp-edged result; he wanted the trashy immediacy of a tabloid news photo."

Bidding adieu to Conservation, we head downstairs to the Marvin Gelber Print and Drawing Study Centre. Here, a more scientific ode to the mechanics of linen production lives on in a leather-bound book with photographs documenting London’s Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations. More than six million people visited the Great Exhibition of 1851, and among the many feats of agriculture, architecture, art, science, manufacturing and engineering on display, was this flax machine, photographed by French photographer and inventor Claude-Marie Ferrier (1811–1889). Unlike cotton, which was easily mass-produced beginning in the early 19th century, linen proved more difficult, the fragile fibres of the flax plant proving resistant to the brute force of machinery. This roller, presented by Lawson & Sons of Edinburgh, would have offered hope for a dwindling industry. At the conclusion of the Great Exhibition, a four-volume catalogue, including this one, was presented to Queen Victoria, and distributed to foreign governments and notables. The decision to illustrate the catalogue with photographs is attributed to Prince Albert, who was very enthusiastic about this new medium. No surprise that proceeds from this hugely successful event went towards the creation of the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Nearby, in the AGO’s Collection of Modern and Contemporary Art, more than a few artists reveal themselves as devotees of linen canvas, among them Helen Frankenthaler, Kenneth Noland and Sean Scully. The renowned American painter Eric Fischl is a loyal fan of linen, as far back as his first solo exhibition at Dalhousie University in 1975. Using a combination of densely layered washes, quick improvisational strokes, subtle lines of dripping paint and a willingness to leave areas of canvas untouched, his paintings exude energy from their surface. While experimenting in the early 1970s, he began cutting corners off square canvases creating rectangular works, suggestive of homes, shields, boats. White House (1975) is one of these, marking the artist’s transition from abstract to figurative painting. In his convocation address to NSCAD graduates back in 2002, Fischl reflected “I came here as an abstract painter and left painting narrative scenes of suburban dysfunction...let us take a moment to bury the memory of the time Gerry Ferguson hung my painting upside down.”

One floor below, in the Thomson Collection of Ship Models, the fully rigged three-masted Georgian-era Revenue Lugger, the Alarm, ca. 1782, sits at the ready with her sails unfurled. A fast ship, she’s called a lugger on account of her four-cornered lug sails, each suspended from a spar, overlapping the mast. An improvement on square-set sails, these lugs allowed boats to sail even closer into the wind, which was particularly useful when catching (or outrunning) pirates. Although this model has silk sails, the original would have had linen canvas sails, made of lengths sewn together in a similar fashion. “Sail-cloth had become a crucial element in world power,” Douglas Hextall Chedzey Phillips-Birt tells us in his book, A History of Seamanship, “and the sources and quality of the pliable flax was a constant preoccupation among maritime peoples. Of all the materials from which sails had been made, flax had proved itself the most suitable…Flax had strength and the great virtue of remaining soft and pliable when wet, the latter of great importance to the handling of sails under bad conditions. But as a corollary of this quality, flax canvas stretched, sagged, and with use lost weight and became porous.”

Reassured somewhat that the new wrinkles in our summer-weight linen jackets aren’t all our fault, but a quality of this fine and ancient material, we conclude our short tour of some of the AGO’s many linen masterpieces. Stay tuned for future material explorations, only in the AGOinsider.