“Tough but a lot of fun”

We talked with art historian Barbara Bloemink about her new biography of Florine Stettheimer, that most audacious, witty and important 20th-century woman painter.

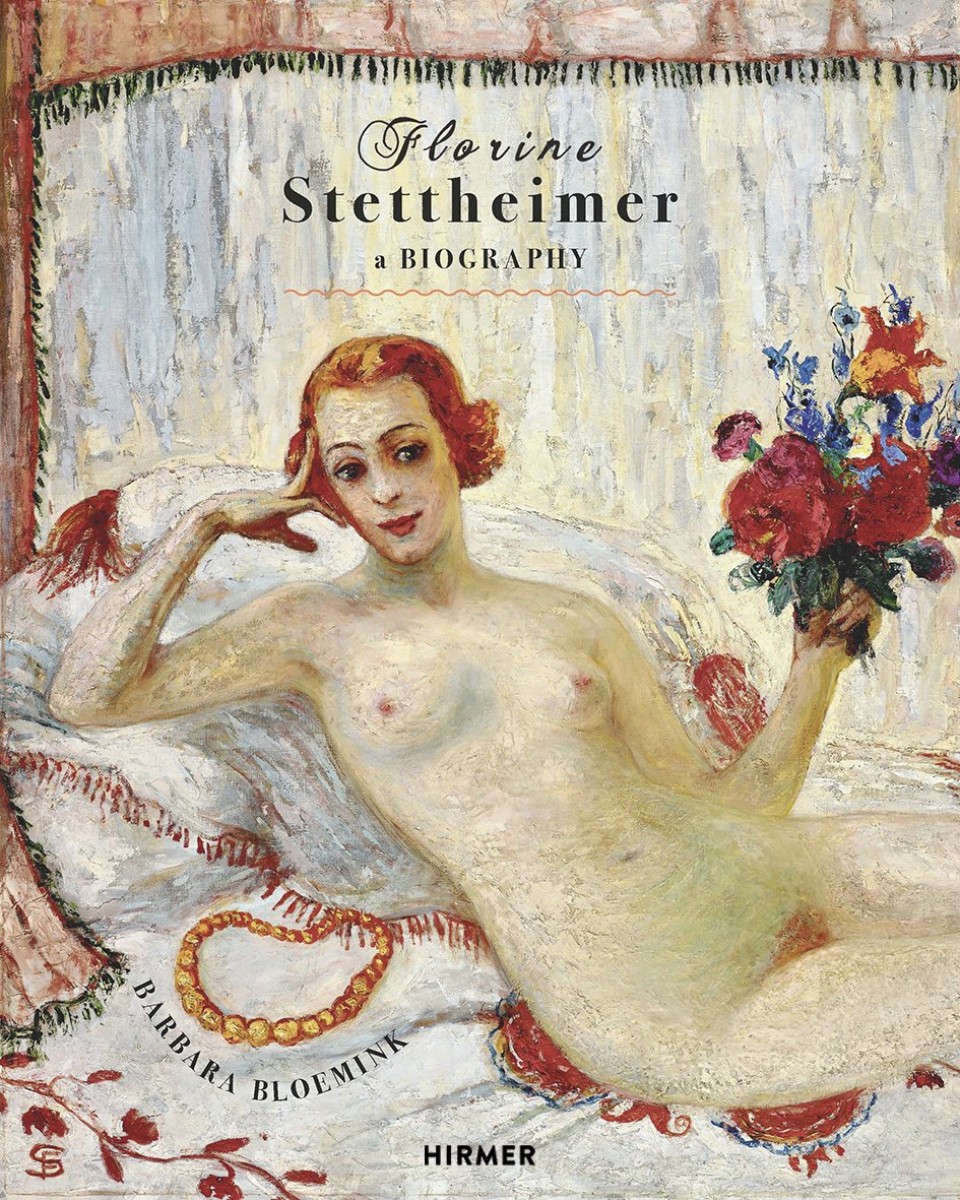

Painter, poet, designer and feminist are only a few of the many words that aptly describe the multifaceted early 20th-century artist Florine Stettheimer (1871-1944) – an undersung pioneer of modern painting in America. It was 2017 when the AGO became the first Canadian museum to exhibit her work, and for those of us still missing her playful, vibrant and psychologically complex paintings, we’re in luck. From renowned art historian Barbara Bloemink comes a detailed new study, Florine Stettheimer: A Biography. We were fortunate enough to catch up with Bloemink following its release last month to learn and see more.

AGOInsider: Can you describe your first encounter with the art of Florine Stettheimer? What keeps you coming back to her as a topic?

Bloemink: I was at Beinecke Library reading letters of Georgia O'Keeffe and found one addressed to someone named Florine Stettheimer describing a funny incident with O'Keeffe's husband, Alfred Stieglitz, falling down in the bathroom. So I went to investigate who Stettheimer was and saw that Beinecke owned five of her paintings and also had her diaries and letters. I fell in love with the paintings which are funny and witty and no one had done a full exhibition of her work since Marcel Duchamp organized her Retrospective at MOMA in 1946. I decided to make her the topic of my Ph.D. which was published by Yale University Press.

The Director of the Whitney Museum of American Art at the time, Tom Armstrong, also agreed to let me organize a retrospective of her work there. I was asked to write a number of essays about her work over the next four or five years but then moved on to curate mostly contemporary art and design. Over the last decade, however, I became dismayed that art critics, curators, writers continued to publish inaccurate statements about her and her work which kept her largely marginalized as an "eccentric, shy, naif-style" artist who was so "devastated by not selling at her first exhibition that she never/rarely exhibited publicly again" or that "she wanted her work destroyed when she died." I believe Stettheimer is one of the most innovative and significant early 20th-century American artists, so I decided to write the first accurate, contextual biography and close reading of her work.

AGOinsider: How does this book differ from or expand upon your previous works about Stettheimer?

Bloemink: My first biography involved finding, identifying and dating Stettheimer's paintings. Many at the time were still labelled as anonymous, and there was no chronology to them. So I pieced together what is left of her diaries and correspondence to put her life and work in chronological order.

AGOinsider: Stettheimer was so many things, had so many facets to her personality – an artist, a socialite, sardonic, German-hating, curious, sensitive, an admirer of Velázquez. What aspect still surprises you most?

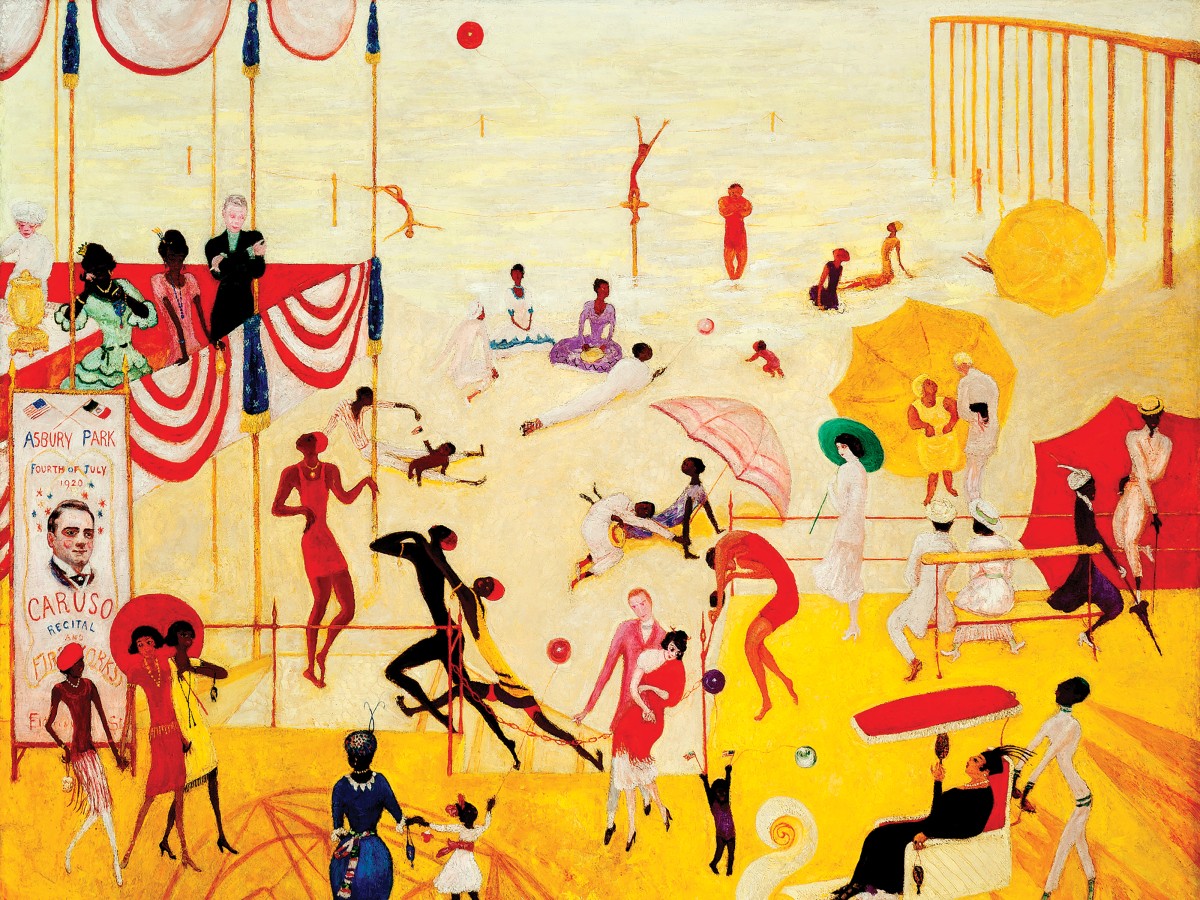

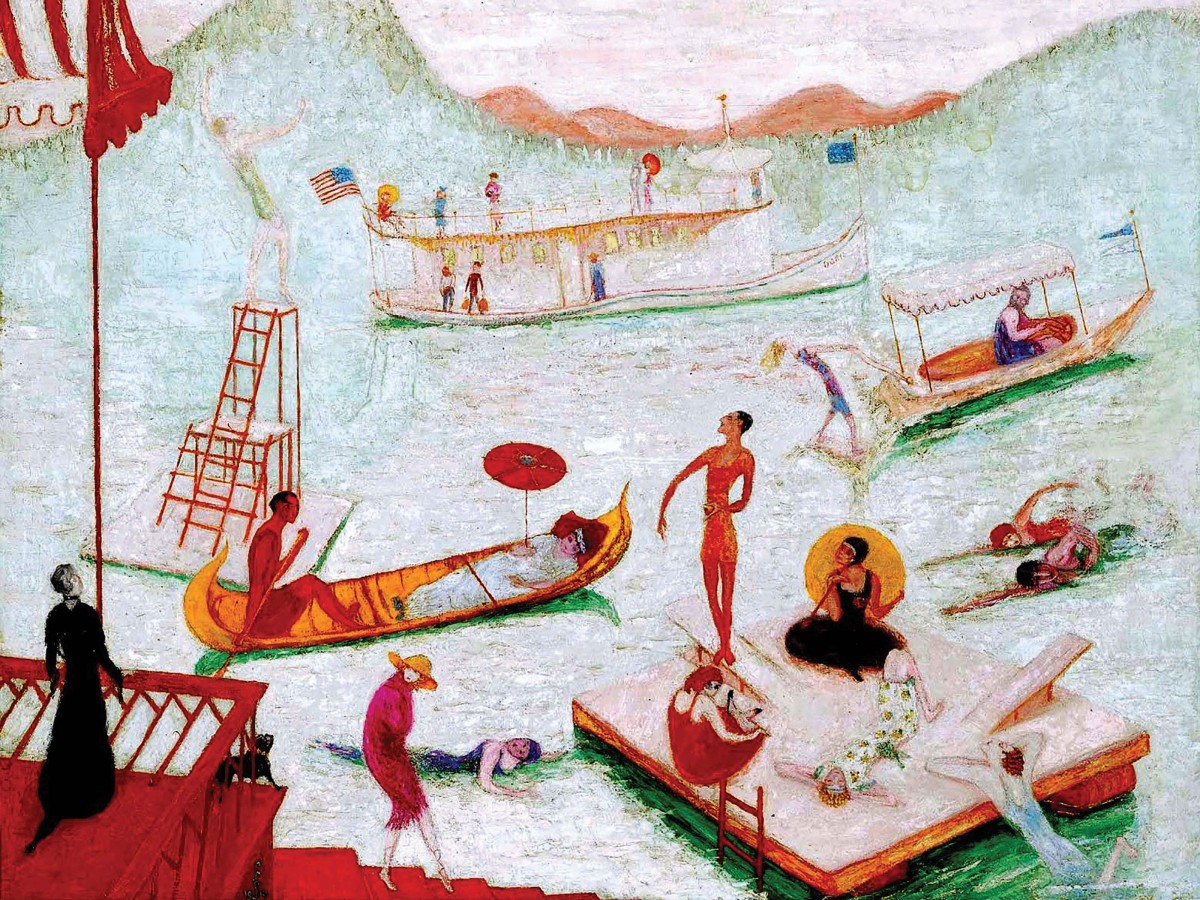

Bloemink: When I first identified (what was then in a box of works titled "not by Stettheimer") the Nude Self-Portrait as being a portrait of Stettheimer, I already knew how audacious it was in art history, but until I did the thorough contextual research into the paintings for this second biography − such as the history of African-Americans at Asbury Park, and Jews in the Adirondacks, for example, I too thought that these were "entertainment" paintings with no political/controversial content. However, once I did the research, and realized that these works are the ONLY ones in which Stettheimer detailed their locations in their titles, it is clear that Stettheimer was well aware that she was subtly revealing her political views in these works. What really shocked me, however, was finding the image of the open labia between Ettie's legs in The Bathers from the 1920s, and a dress covered with swastikas in Beauty Contest. The latter painting has been hanging on the museum's walls and exhibited widely for years, and no one noticed it!

AGOinsider: You co-curated an exhibition of her work for the Whitney in 1995. Did the act of installing her works, choosing and hanging them in a defined space for an audience, change your perspective or understanding of them at all?

Bloemink: All I am going to say about this, as it is very controversial for me, is that I have never yet seen an exhibition that truly captures, thematically, aesthetically, or in any way that highlights Stettheimer's significance as a 20th-century innovator or her continuing relevance today. The closest was sections of the re-hang at the AGO in 2018.

AGOinsider: You describe Stettheimer as “one of the first American multidisciplinary artists.” Is there a quality or common thread that binds her many creative pursuits?

Bloemink: Absolutely − wit and intelligence. Throughout her work, from very early on, there is subtle, often biting humour that is light and fast and intelligent. She did not suffer fools and would have expected a highly intelligent, cultured audience to catch her many references hidden in plain sight throughout her work. Nothing ponderous or heavy but very contemporary and of the moment − also a clear line that runs through her work from the Orphee ballet − which has no relation to the Bakst designs but was already far more contemporary in terms of the costumes − and a detached observer.

AGOinsider: You talk about how misconceptions of Stettheimer were the motivation for this book. Do you think these misconceptions linger because of inattention or because her paintings embrace both high and mass culture?

Bloemink: Both − over and over again in museum labels and written descriptions of her work people have described it as "faux-naif", "child-like" − words I would love to see applied to Marsden Hartley's work but of course, as he was a man, they never are. But compare his portraits or figural group works to hers. Unlike Hartley's, Stettheimer's portraits are quite close to their subjects' features. Referencing her extensive education, training and skill, her paintings are filled with direct references to Old Master and 19th-century painting motifs. She uses perspective and chiaroscuro (the use of strong contrasts between light and dark) throughout her works: learned from her French and German academic training.

And then the idea that her works are "decorative fantasies" is bizarre when you actually look at them. Stettheimer carefully researched her paintings: I have been able to identify most of the actual buildings in many of her paintings. Her painting Christmas for example, for years was labelled as Rockefeller Center despite the fact that in the middle, it has a column with the figure of Christopher Columbus, the characteristic Central Park benches in the front, and all the buildings surrounding the statue of Columbus can be identified as existing in situ circa 1934. When Stettheimer painted her Cathedrals of Wall Street, she visited the Salvation Army to study their uniforms, sent away for a copy of a navy uniform so she would reproduce it accurately and factually reproduced all the buildings − from the Stock Exchange and Trinity Church to the statue of George Washington that still stands there today. Stettheimer was an urban "Documenter" of the avant-garde and popular life and architecture in New York between the world wars, not a decorative painter.

AGOinsider: Your book notes occasions where her sister Ettie has deleted/excised sections from her diary/correspondence. Do you think these omissions, had they remained, might change how we see Stettheimer?

Bloemink: Yes, from a tiny bit that was left about her nephew not seeing her before leaving for the war, I think she could be quite emotional in private. She was an introvert − although she was a snob and had a biting sense of humour she shared with her very closest friends − I think she probably had a temper and strong emotional life that is glimpsed in some of her poetry. I am convinced that she and her sister Ettie never got along, so as soon as Rosetta the mother died, she moved out completely. Ettie cut out everything she said was "personal" − so we know nothing about Stettheimer's feelings except what we can glean from her wonderful poems, and the humour in her paintings. It's too bad as I think she was probably tough but a lot of fun.

Be sure to subscribe to the AGOinsider for upcoming stories from the world of art and culture, delivered every week into your inbox.