What’s made in the mold

Continuing our exploration of artistic materials, we cast our eyes over the many ways plaster leaves an impression.

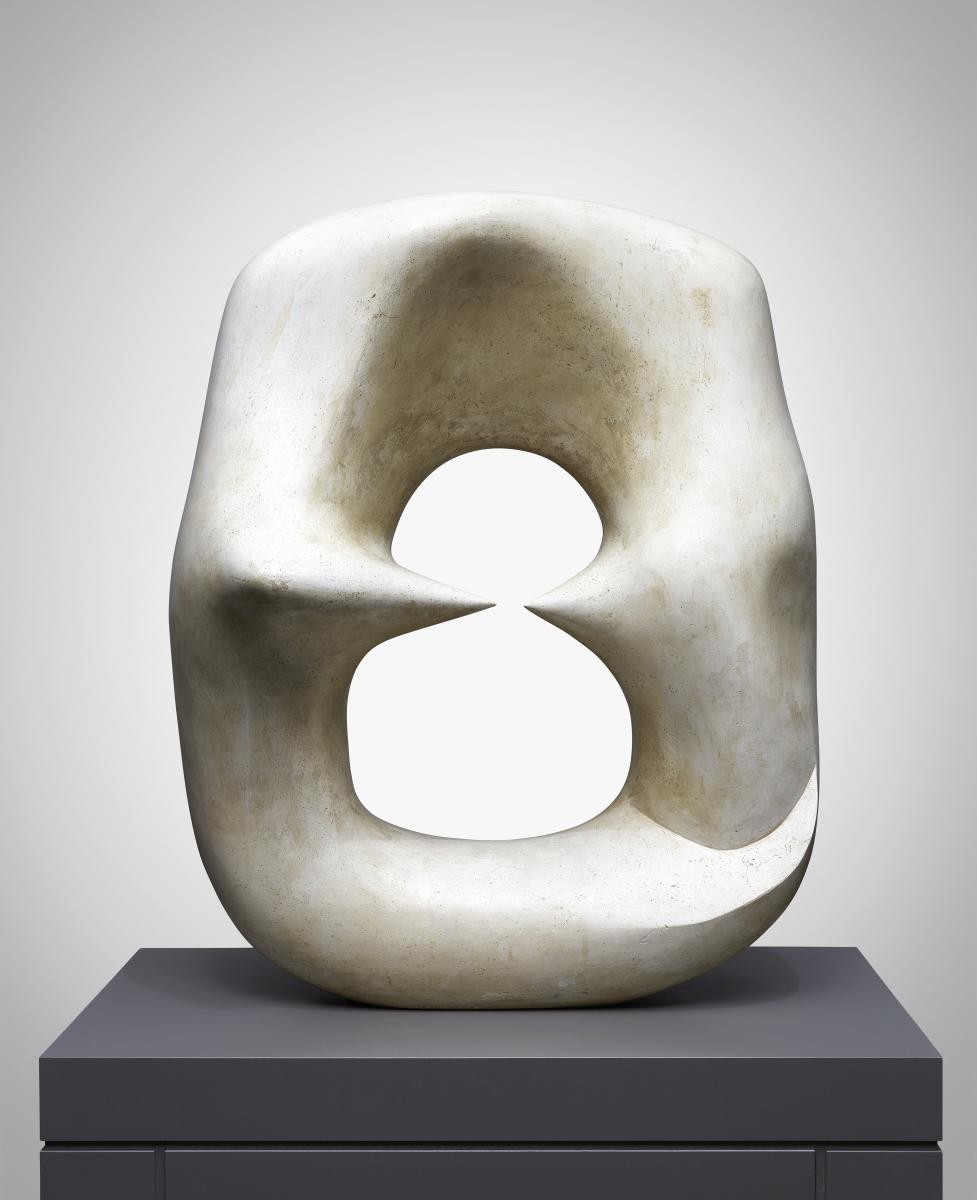

Henry Moore. Reclining Figure, 1956. Original plaster, Length: 236 cm. Gift of Henry Moore, 1973. © Henry Moore Foundation / SOCAN (2021) 73/77

A hockey player two metres tall, a wall of footprints and a shelf of future fossils – the AGO is home to a world-class selection of plaster artworks. Used by everyone from ancient Egyptians to the avant-garde to create replicas and original artworks, plaster is as enduring and brittle as memory itself.

Molded when wet and carved when dry, plaster can be used for sculpting, wall coverings and ceilings. It makes detailed impressions and, when protected, is very durable.

“Its only enemy,” says Lisa Ellis, AGO Conservator, Sculpture and Decorative Arts, “is humidity. Which is funny because water is a main ingredient. Although many varieties of plaster exist, the basic recipe for artists – what we call plaster of Paris, after the large gypsum deposits outside Montmarte – is relatively simple. You heat gypsum until it becomes a powder, and mix that powder with water. An exothermic chemical reaction then occurs, which means that as you mix it, it gets hot, hot enough to burn skin, and then hardens quickly.”

The drawbacks to using plaster made this way? “It shrinks a bit as it cools, meaning that there is a risk of bubbles and surface imperfections. Uncoated plaster surfaces are easily stained by liquid and it’s not very strong – which means for large works, artists usually want to layer plaster over wood or paper or straw, to reinforce them. Unfortunately, these lightweight internal supports are susceptible to rot and damage due to humidity, when can cause the sculptures to collapse. The Romans knew these liabilities and created a variation of plaster with lime and volcanic ash, similar to cement, that still survives today,” says Ellis.

“Frances Loring’s Goal Keeper (c. 1935), for example, is a work that is made of multiple layers of plaster, applied on a chicken wire form, with layers of soaked jute in between. It’s almost like papier mache.” A sympathetic rendering of an athlete made in epic proportions, Loring couldn’t afford to cast such a sportsman in bronze, so instead painted him green, hoping to mimic the appearance.

But on the plus side, adds Ellis, plaster is easily manipulated – it can be carved, shaped and polished, with tools as simple as sandpaper. So highly polished and finished is Henry Moore’s Working Model for Oval with Points (1968–1969), it resembles marble.

Home to the world’s largest public collection of Henry Moore’s work in the world, the AGO has more than 87 plasters in its Collection, some no larger than an egg and others monumental in scale. Inspired by objects found in nature – stones, leaves, sticks – Moore often added to these naturally occurring shapes many layers of plaster to create his iconic swelling masses and rounded voids.

Ellis reminds us that despite outwardly resembling monolithic stone structures, Moore’s large plasters are in fact very functional objects, meant to be dissected for molding, with a thin skin and lightweight interior structure. Hanging around inside foundries, many have a green tinge, the result of copper dust settling on their surface. Poised for action, Moore’s Reclining Figure (1956) is a good example of a monumental sculpture whose expressive energy and scale belies its real weight.

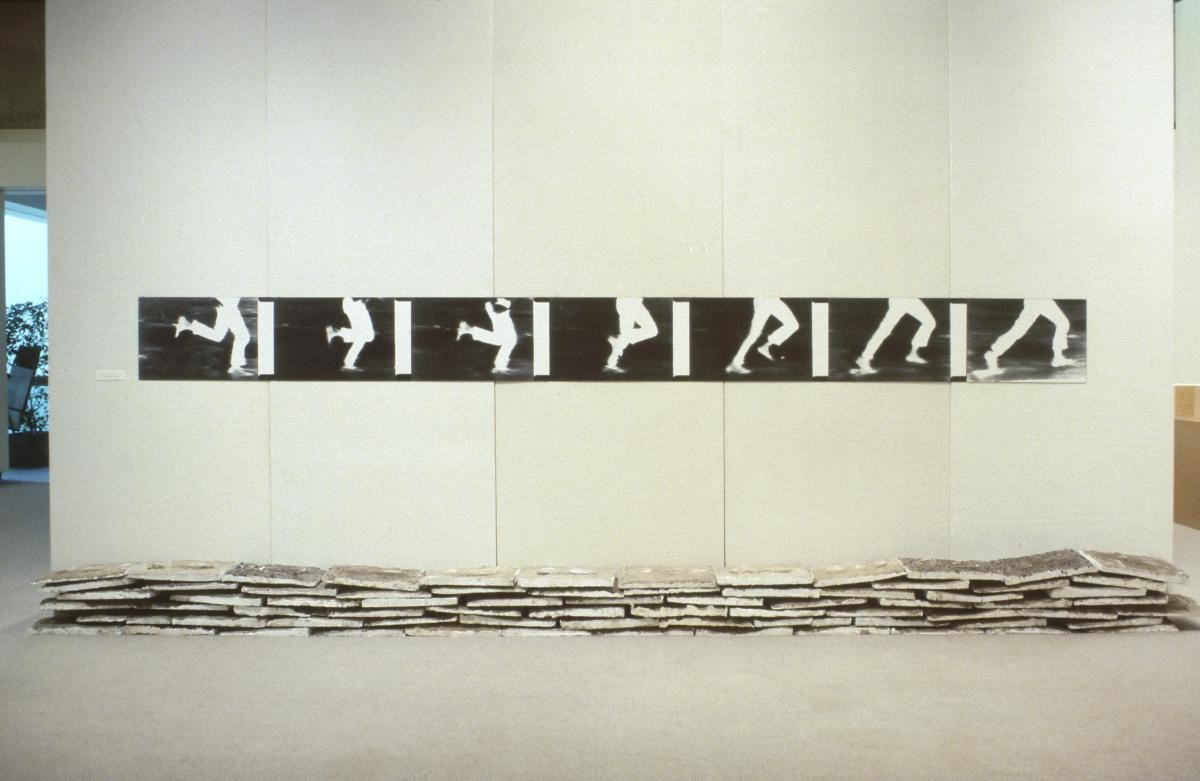

Speaking of energy contained, in 1969, the American artist Dennis Oppenheim (1938–2011) memorialized a run he did behind the Art Gallery of Edmonton in an artwork. Using a one square foot wooden frame, Oppenheim captured every step of that sprint in plaster. Tightly stacked into a long low wall, positioned beneath a series of six black and white photos, these plaster casts encrusted with dirt are the basis of his installation, Condensed 220 Yard Dash (1969). “Forcing out space between a series of steps,” he said, “is like eradicating time intervals between notes. The result is a single sound unbroken by silence. The museum walls echo the solidified vibrations of exterior distance."

When the major retrospective Andy Warhol opens this summer, visitors to the AGO will experience the sunlit spaces of the Henry Moore Sculpture Centre anew. Although temporarily removed to make space for Warhol, like so many ghosts in the room, Moore’s sculptures will be gone, but the presence of them will no doubt remain. “Plaster has a ghost-like unreality in contrast to the solid strength of the bronze,” said Henry Moore in 1986, a sentiment that is reaffirmed by the work of contemporary sculptors George Segal, Adrian Villa Rojas and Rachel Whiteread.

The son of a kosher butcher, George Segal’s installation The Butcher Shop (1965) may have been conceived as a homage to the artist’s father, but it is the artist’s mother who is immortalized. Unpainted, her plaster form is seen at the table, cutting the head off a chicken. The window, the saw, the black mirror and racks are all authentic, purchased from a New York City supplier. But, to sculpt his human forms, Segal would wrap models in plaster-dipped orthopedic bandages meant for medical casts, removing the wrappings after they had hardened and re-assembling them in order to make a hollow plaster shell of the model’s full body. The mummy-like quality of the plaster figure lends the installation a certain ominous quality.

Rising from an angular brick base to show us aspects of ourselves, the shelving units of Adrián Villar Rojas's installation Today We Reboot the Planet (2013) are home to a variety of small sculptures in various media. Molded from familiar objects – car tires, plants, Kurt Cobain’s body – his installation propels us into a post-human future of ruins, where these objects will exist as fossils.

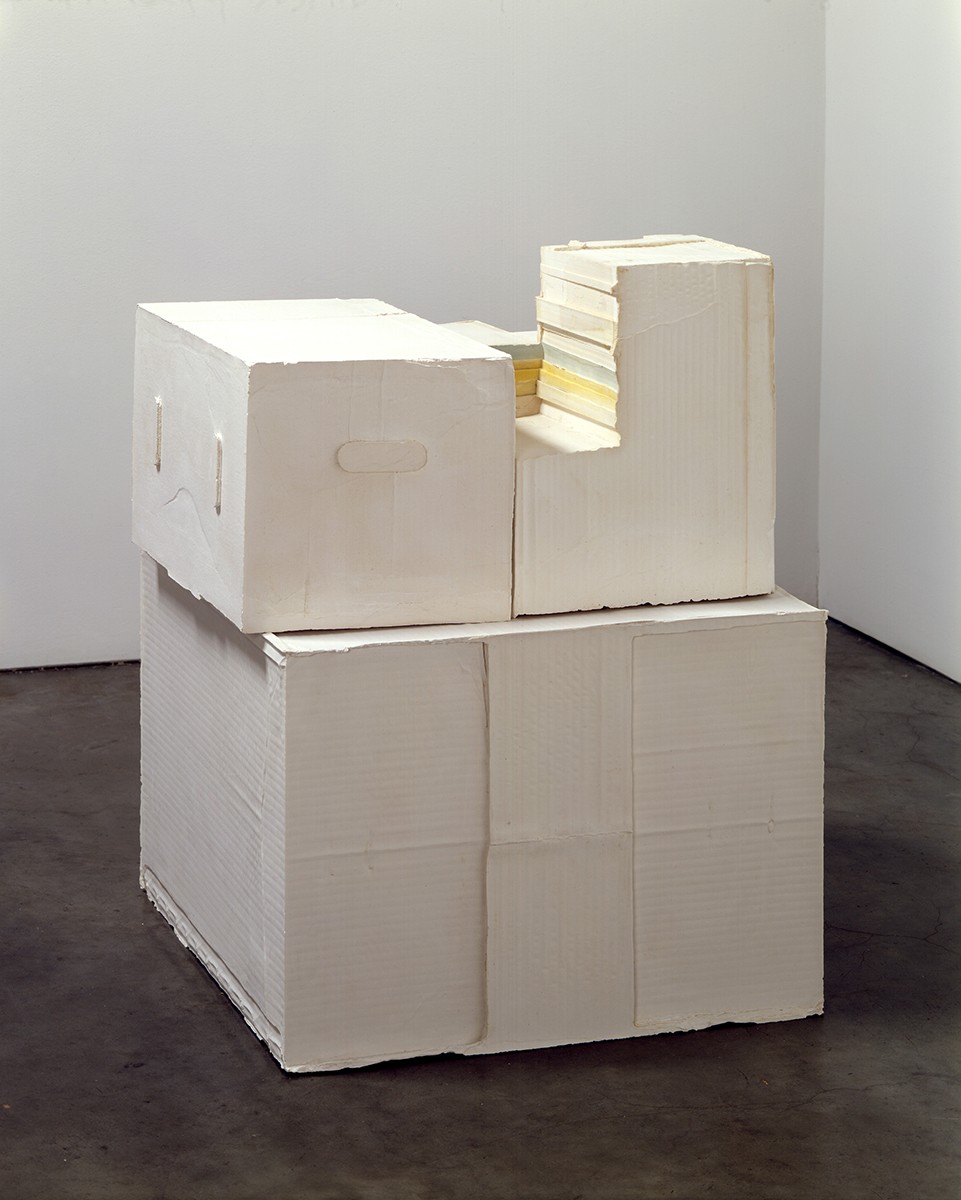

In 2004, British artist Rachel Whiteread began plastering the inside of cardboard boxes. Her motherpassed away in 2003 and in the process of sorting through her belongings, the artist came across box after box of various items – papers, photos, tapes – that she recognized from her childhood. She realized something as humble as a worn cardboard box could be a potent site for memory. By filling the boxes with plaster and peeling away the exteriors, she created perfect casts, each one recording and preserving all the bumps and indentations on the inside. In Stack II (2005), a recent AGO acquisition, her ghostly plaster sculpture reveals the molded imprints of books.

However ghostly or exact a replica, these sculptures keep us enthralled with their ability to make palpable past experiences or project us into speculative futures. Stay tuned for future material explorations, as the AGOinsider takes you beneath the surface and into the AGO Collection.