Silver sheen

For the next entry in our Material Explorations series, we look at the lustrous history of the ever-present, ever-precious metal, silver.

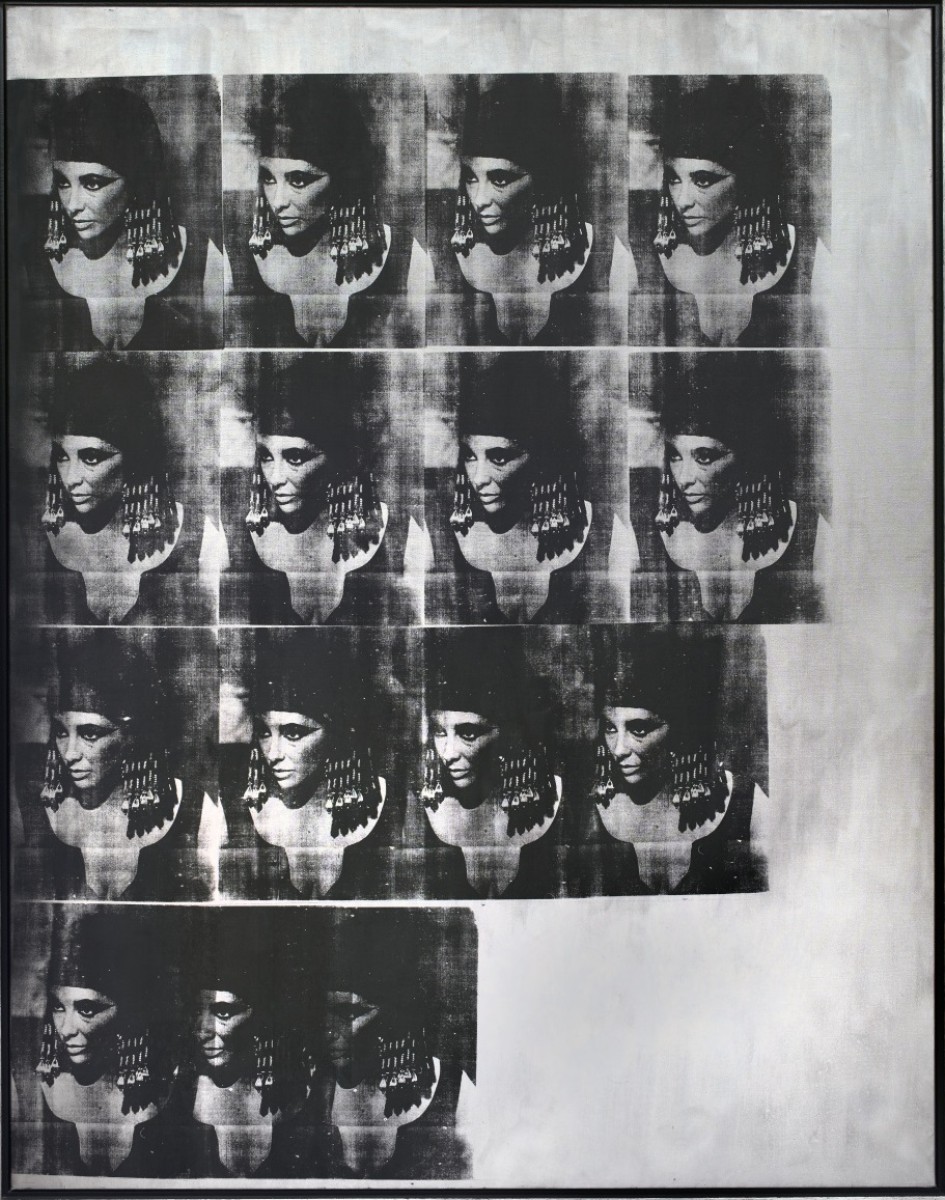

Andy Warhol, Silver Liz as Cleopatra, 1963. Silver paint, silkscreen ink, and pencil on linen. Framed: 212.4 x 169.5 cm. Gift of Mrs. Else Landauer, in memory of her husband, Walter Landauer, 1979. © 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOCAN. 79/114.

When you think of silver, what comes to mind? “I’ve always said that silver was my favourite colour because it reminded me of space,” Andy Warhol wrote in 1975. Silver is at once futuristic and of the past, both as a colour and precious metal. Its metallic sheen has a white-ish glow that can be reflective. It’s malleable and conductive. It oxidizes and corrodes. It has been used as coinage several times over, from India to China to the UK and Ancient Greece, with some coins dating as far back as 600 BC. When combined with other metals as an alloy, like sterling silver, for example, it can be manipulated into everyday objects. Buried deep inside the earth’s crust in its purest, native form, traces of silver metal are all around us, from our cutlery and jewellery to our electronic devices and medical equipment. This doesn’t account for objects that appear silver because of their colour, whether seen in another metal like steel or painted on a canvas.

For a time, silver suggested sophistication, decadence and wealth; a reputation based in truth—until it wasn’t. Silver is a cheap metal, but at certain points in history, it was more valuable and sought after than gold. Ancient Egyptians adorned themselves with silver jewellery when preparing for the afterlife, beginning as early as the Predynastic period. “The value of precious metals has to do with their scarcity,” says Lisa Ellis, AGO Conservator, Sculpture and Decorative Arts, “In ancient Egypt, silver was much more valued than gold because while they had an abundance of gold, silver was harder to attain. One of the reasons why gold and platinum are so valued today is because they aren’t as chemically reactive as silver.” Silver was first mined thousands of years ago in what is now Turkey, eventually shifting to Greece and Spain. It was one of the main resources extracted from Central and South America to enrich European empires. In pockets around the world, the development of silver mines began in the late 19th century.

Since then, because of accessibility and changing tastes, silver has placed second best to its most famous counterpart, gold. It’s a publicly-traded commodity, and despite more than one global silver shortage and steadily rising prices in recent years, it has a significantly lower value. Not to be completely outdone by gold, silver’s ubiquity extends into the English language. The expression, “born with a silver spoon in their mouth” suggests someone born of considerable, often inherited, wealth. Someone with a “silver tongue” is persuasively well-spoken. A cloud’s “silver lining” reminds us to focus on the positives of negative scenarios.

Taking a look within the Gallery, we couldn’t pass up the opportunity to do our own silver mining in the AGO Collection, where we discovered the AGO has more than 2,000 objects in the Thomson Collection of European Art alone. Roughly 50 to 60 of them are metalware pieces and sculptures made with silver.

Meditation and the Medieval Mind, an ongoing exhibition located on Level 1 of the Gallery, contains select works from the Thomson Collection of European Art, including a mid-16th century prayer book and a 17th-century miniature book finely gilded with silver. “In more historical paintings and works, like those from the 14th century and onwards, silver was at times used as a more affordable alternative to gold,” says Meaghan Monaghan, AGO Conservator, Paintings. “For frames and fine detail work, artists would gild silver leaf, and then tone it with a yellow paint so it would look like gold.” Also on Level 1 of the Gallery, Diptych: The Annunciation and the Man of Sorrows (ca. 1410) by Gonçal Peris Sarria is on view. In the right panel, the angels placed in the background look to be gilded with silver that has tarnished and darkened over time. Could this be an example of this resource-saving silver leaf technique? Possibly, but without an in-depth chemical analysis, it’s impossible to know exactly which metal has been used.

Fast forward to the 20th century. Andy Warhol, who famously donned wigs topped with grey-silver hair, revisited silver more than once in his work. And with his major exhibition on view until late October, we can see his well-documented use of the metal. “Silver was the future, it was space-y,” he recounted, “The astronauts wore silver suits. [Alan] Shepherd, [Gus] Grissom and [John] Glenn had already been up in them, and their equipment was silver. too. And silver was also the past–the Silver Screen–Hollywood actresses photographed in silver sets." Acquired by the AGO in 1979 and on view in the exhibition, Silver Liz as Cleopatra (1963) (image above) is one in a series of portraits Warhol made of Elizabeth Taylor in the early 1960s and one of many celebrity portraits he made. Taylor, a cinematic icon from Hollywood’s silver screen and perpetual tabloid fodder, appears silkscreened 15 times on the left side of a hand-painted silver canvas. The image is lifted from Taylor’s turn as the titular character in the 1963 film Cleopatra, a notoriously fraught production that was once the most expensive films ever made and went on to become the highest-grossing film of 1963. Taylor was paid more than $1 million for her portrayal–a landmark earning–making her the first actor to ever receive that amount. It’s no secret that Warhol had a fascination with celebrities. Much like contemporaries Marilyn Monroe and Judy Garland, Taylor represents the glamour and tragedy of 20th century Hollywood. Through this painting, Warhol comments on the fantasy and illusion of the silver screen. The strips of repeated silkscreen images are placed on the silver-painted background as if to hover over it. Silver Liz as Cleopatra (1963) and Elvis I and II (1964) are two of a small number of paintings in the AGO Collection that contain silver-coloured paint.

Around the same period, Warhol extended his fondness of silver to The Factory in midtown Manhattan. He tasked his collaborator and former partner Billy Name to cover the experimental art studio and gathering space in silver paint and reflective aluminum foil. It was in this large loft where mass production of Warhol’s paintings, sculptures and films took place. It quickly became a popular haunt for New York glitterati, attracting artists, friends and celebrities looking to partake in artmaking, and sometimes drug use. In 1966, Warhol unveiled Silver Clouds (1965-66) for the first time at Leo Castelli Gallery in New York. These helium-filled floating “pillows”, as they were once referred to, are made out of a silver laminate called Scotchpak. Echoes of Silver Clouds can be seen in Yayoi Kusama’s INFINITY MIRRORED ROOM - LET’S SURVIVE FOREVER, also part of the AGO Collection.

Warhol is known for his photography. His gelatin silver prints, such as his series of stitched photographs, make up a dedicated portion of the exhibition. But, what is a gelatin silver print exactly, and how is silver involved? The AGO has thousands of them in its Collection. A fibre-based gelatin silver print has four layers: a paper base, a baryta layer, a gelatin silver halide binder and a protective gelatin overcoat. In basic terms, silver comes in the form of silver halide particles suspended in the gelatin binder, which holds the photographic image. Highly sensitive to light, silver halides are chemical compounds formed with silver and halogens like bromide and chloride. To the naked eye, these prints don’t often look to have any form of silver in them. A well-printed, well-conserved gelatin silver print can appear warmer in tone (in part because of the gelatin binder and overcoat) with varying shades of grey, black and brown. The details of a print increases with the amount of silver halide in the photographic paper; the more silver, the more detailed the print can appear.

The first consideration for any gelatin silver print entering the Collection, or preparing to be exhibited, is its condition. “What I need to look at is if there is a breakdown of those layers,” Katharine Whitman, AGO Conservator, Photography, explained. “The layers need to be stabilized if the photograph is going to be exhibited safely.” Without proper protection from pollutants and fluctuations in humidity, a gelatin silver print can deteriorate as it ages. It may begin to look faded and discoloured with a yellow tone. Denser areas of the print can even take on a white-ish mirrored cast known as “silver mirroring”. This occurs when the filamentary silver halide particles begin to break down (like steel wool breaking apart) and accumulate into a cloud of broken smaller particles that can eventually migrate to the front-facing part of the image. West Indies Regiment Soldiers—a 1930 gelatin silver print from the Montgomery Collection of Caribbean Photographs—has some evidence of very minor “silver mirroring” along its left and right edges (see detail image). This doesn’t take into account physical wear and tear that can occur over time in the form of cracking and, in some cases, even mould. Some of the fibre-based gelatin silver prints from the Andy Warhol exhibition for example, had minor abrasions along their edges.

The daguerreotype process predates the popularization of the gelatin silver process by a few decades. Invented by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, it's the first form of photography, and includes silver as well—an image created on a sheet of polished, silver-plated copper. The introduction of the gelatin silver process in the late 1880s, however, changed photography fundamentally. “It became popular in the 1880s because it was replacing photographic processes that were even more complex, labour intensive, and could only be professionally done,” explains Whitman. “The introduction of gelatin silver photography made it possible for anybody to take photographs.” Anyone with access to a camera, like a Kodak “Brownie” box camera, could take their own photographs, and have them developed and printed for them. The gelatin silver process remained a popular choice for professionals and hobbyists alike well into the 20th century. Nearly all photographs up until roughly the 1970s were fibre-based gelatin silver prints. The widespread popularity of colour photography in the 1960s and digital photography in the 1990s ultimately led to the gelatin silver process becoming less common. A variety of gelatin silver prints from the AGO Collection are on view on Level 1 in Documents, 1960s-1970s. Fragments of Epic Memory will feature a selection of just over 200 images from the Montgomery Collection of Caribbean Photographs beginning this September, including several examples of gelatin silver prints and daguerreotypes taken in the post-emancipation period in the Caribbean.

Stay tuned for more Material Explorations on AGOinsider. If you haven’t already, this one about linen dives into Warhol’s Elvis I and II (1964). This one speaks about plaster and this one about lucite